Book Review

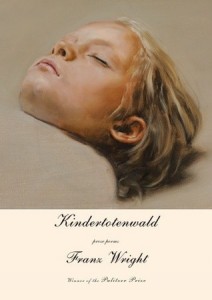

“At this point I think you might want to sit down, pour yourselves a drink, and fasten your seat belts in preparation for what I am about to divulge,” writes Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright in his new collection of poems called Kindertotentwald. This is good advice for anyone sitting down with a book of Wright’s poems. His poetry consistently finds its impulse and energy in spiritual crises. His taut lines and calculated cadence allow for a confident voice, even as he himself explores the boundaries of doubt, ceaselessly seeking redemption. Unlike the magnitude of a grand cathedral, inevitably drawing our eyes up, Wright’s cathedrals are found swirling in a glass of amber whiskey or in the quiet of dark woods, drawing our eyes deeper into the familiar: family, childhood, addiction, faith.

“At this point I think you might want to sit down, pour yourselves a drink, and fasten your seat belts in preparation for what I am about to divulge,” writes Pulitzer Prize-winning poet Franz Wright in his new collection of poems called Kindertotentwald. This is good advice for anyone sitting down with a book of Wright’s poems. His poetry consistently finds its impulse and energy in spiritual crises. His taut lines and calculated cadence allow for a confident voice, even as he himself explores the boundaries of doubt, ceaselessly seeking redemption. Unlike the magnitude of a grand cathedral, inevitably drawing our eyes up, Wright’s cathedrals are found swirling in a glass of amber whiskey or in the quiet of dark woods, drawing our eyes deeper into the familiar: family, childhood, addiction, faith.

In Kindertotenwald, a word loosely translated as “forest of dead children,” Wright cultivates an ethereal, otherworldly landscape. Though still emotively powered, anchored in both the visceral and cognitive, Wright trades his characteristic condensed line for prose form. The prose poem has certain demands but also certain allowances. For Wright, it offers a broader canvas for narrative emphasis and concentrated philosophical inquiry. For example, in the poem “History,” the shirt of late poet Frank Stanford and a walk past a former elementary school provoke an embrace of memory, while recognizing its finite dependence on our existence: “There are three worlds. We know them as the three words present, future, past. And from here it looks like I was standing for a minute, at the age of twenty-seven, in all three of them at once.”

The poems of Kindertotenwald concern themselves, rather obsessively, with this filmy and spectral blurring of past and future, that is: the present. Ungraspable and capable of monumental beauty, the present is always, irrevocably, slipping into the past. “This is a matter of grace, but also a cruel and conditional ecstasy, one no mental effort can prolong, one that in fact consists of the grievous poignancy with which it bleeds away, fading and vanishing almost before it has fully begun,” writes Wright in “The Poet.” The present moment is a crux of anxiety: memory’s fallibility on the one hand and desire for culmination—a final, definitive outcome—on the other. It is in on the border of these that the poet, by nature of occupation, must find himself.

Such a prolonged exploration of our dynamic, shifting presence in the world can only be couched in a prolonged exploration of death. Wright’s aesthetic world is a world of contradiction and paradox, estranged opposites finding common ancestry: beauty blooms from suffering, love from rejection, the sacred radiates out of the unsacred, and we know life because of the certainty of death. “Am I ever going to witness a form of beauty that is not the child of death?” wonders Wright in “In Memory of the Future.” And in the poem “Imago”: “We have misnamed death life and life death.” At the nucleus of this combustible relationship between life and death is faith. Are we not most human when feeling broken? It’s strange but true how often we experience beauty and suffering simultaneously. Similarly, encounters with divinity are often shadowed by nihilistic impulses, encounters with emptiness. This is the influence of death on the living. As Wright repeats throughout his poems, “Light is the shadow of God.”

If you haven’t read the work of Franz Wright, start with God’s Silence or Walking to Martha’s Vineyard, for which he won the Pulitzer Prize. While Wright deftly maneuvers through the prose form in Kindertotenwald, at times the poems fall from trusted narrative into proverbial parable. His best work happens at the intersection of emotional transparency and linguistic precision, where even his most definitive claims embrace mystery: “A poet should carry death’s imminence with him at all times, the way a priest might his black book of extremely small psalms” (“History”). Overall, Kindertotenwald is an earnest movement of thought, a synaptic map of aging, mortality, and memory. Be sure to take Wright’s wise advice. Settle in with a glass of your preferred bourbon or IPA and prepare for a philosophical and paradoxical jaunt through everyday moments of immense beauty and unrelenting tragedy. In his poem “On My Father’s Farm in New York City,” the reader is given more advice, and it is perhaps the most important: “Don’t look at my finger, look where it’s pointing.”

About the Reviewer

Caitlin Mackenzie’s writing has been included in Plain Spoke, MiPOesias, Glass Poetry Journal, and Forge, among others. After graduating from the Bennington Writing Seminars, she moved to Eugene, Oregon, where she currently lives and works in academic book publishing.