Book Review

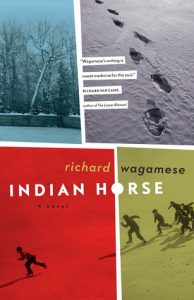

As an avid reader of Native American* literature, I held Richard Wagamese’s slender novel, Indian Horse, between my fingers longer than I do most before cracking it open. The cover art of a quiet, snowy landscape with barn-like buildings on the horizon hinted at a disquieting undertow that promised dark revelations. I’ve learned that sometimes these revelations reach off the page and hurt you deep in your soul. Stories of Indian boarding schools in the United States and Canada—whether in memoir or fiction—are uniformly heartrending. They keep company with Cynthia Ozick’s “The Shawl” and Tadeusz Borowski’s “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentleman” in reminding us that humans possess an astounding capacity for cruelty. I girded my heart and opened the book. But hockey?

As an avid reader of Native American* literature, I held Richard Wagamese’s slender novel, Indian Horse, between my fingers longer than I do most before cracking it open. The cover art of a quiet, snowy landscape with barn-like buildings on the horizon hinted at a disquieting undertow that promised dark revelations. I’ve learned that sometimes these revelations reach off the page and hurt you deep in your soul. Stories of Indian boarding schools in the United States and Canada—whether in memoir or fiction—are uniformly heartrending. They keep company with Cynthia Ozick’s “The Shawl” and Tadeusz Borowski’s “This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentleman” in reminding us that humans possess an astounding capacity for cruelty. I girded my heart and opened the book. But hockey?

I’ll get to hockey in a minute. First, Wagamese does not shy away from the savage events so many suffered in institutions designed to remove the “savage” from Indian children. But he doesn’t dwell there, either. Mercifully, he brings it to us in tiny moments both direct and subtle, such as when a group of children escape the school for an afternoon at the creek.

We could see the fish pushing up that water. It was thrilling. So much life, so much desperation, so much energy. . . . We lowered the sacks into the water and pulled them up dripping and filled with fish. We watched the silvery, brown flash as they flopped out on the bank, their puckered mouths flapping like wet kisses from fat aunties, their tails flipping and slapping against the ground. . . . We did that four times. The fourth time we stood quietly, each of us lost in our thoughts, as the fish struggled for air, for life, for freedom. . . . [I]t was ourselves we saw fighting for air. We were Indian kids and all we had was the smell of those fish on our hands.

When a young new priest arrives at the boarding school during the late 1950s, he brings with him the game of hockey. In used equipment on a small homemade rink in the field behind the school, the older boys learn to play Canada’s pastime. Saul Indian Horse takes to it like a fish to water. Even before he’s old enough to play on the team, he is allowed to clean the ice, and he practices in the pre-dawn hours with wadded up paper in the toes of his oversized skates, using a stick he hides in the snow and frozen horse turds as pucks. He focuses so keenly on the game that he develops a vision for understanding his opponents—a vision that allows him to take command of the game with well-practiced speed and skill. He also finds the camaraderie of teamwork, as well as respect and acceptance from boys older and bigger than he. But this novel is about playing hockey while Indian—being a star player, a kid with a real chance to make it big in a time and in a world that is only willing to look so far past the color of your skin.

I wanted to rise to new heights, be one of the glittering few. But they wouldn’t let me be just a hockey player. I always had to be the Indian. The fans picked up on it. During one game they broke into a ridiculous war chant whenever I stepped onto the ice. At another, the announcer played a sound clip from a cheap western over the PA. . . . A cartoon in one of the papers showed me in a hockey helmet festooned with eagle feathers, holding a war lance instead of a hockey stick.

With his 220-page story of Saul Indian Horse, Wagamese delivers a near-perfect analogy to the history of the First Nation peoples of Canada. From the rich, traditional Ojibway life Saul shares with his grandmother in the northern Canadian bush, from the government men who took the sister he never knew and the brother he could never forget, to the sudden and devasting loss of culture and the new, unsettling identity delivered by the hands of the Catholic Church. From the hope of achieving something bigger than himself to the crushing racism of postcolonial North America and the lasting effects of abuse. And finally, the long journey home again. It is a beautiful feat in a compelling read—a final gift from Richard Wagamese who died in March of 2017 at the age of sixty-one. Indian Horse was first published in 2012 and won the Burt Award for First Nations, Métis and Inuit Literature in 2013.

*Native American and First Nations are both terms used to depict the indigenous people of North America. Native American is most often used in the United States, and First Nations is most often used in Canada. Indian is the term Wagamese uses in the novel.

About the Reviewer

Heather Sharfeddin is the author of five novels. Her work has earned starred reviews from Kirkus Reviews and Library Journal, has been honored with an Eric Hoffer award and honored at the New York and San Francisco Book Festivals, as well as the Pacific Northwest Book Sellers Association. She has taught creative writing at Randolph-Macon College, University of Arkansas at Little Rock, and Linfield College. Sharfeddin holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and a PhD in creative writing from Bath Spa University (Bath, England).