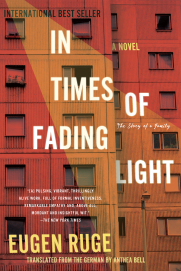

Book Review

As Eugen Ruge’s novel In Times of Fading Light opens, the year is 2001, the place is a town named Neuendorf on the outskirts of Berlin—a town formerly in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Communist eastern half of Germany—and the characters are forty-seven-year-old Alexander Umnitzer and his aged father, Kurt. Still living in the decaying home where Alexander grew up, Kurt was once a prominent historian in the GDR. But by 2001, Kurt has trouble remembering how to eat his goulash and red cabbage with a fork. His language is almost entirely lost except for the word yes. Alexander, as he sits in his father’s study at his tiny desk, looks at the bookshelves and observes that the scholarly books and articles Kurt wrote “occupied a total expanse of shelving that could almost compete with the works of Lenin: a meter’s length of knowledge. . . . And now all of it, all of it was wastepaper.”

As Eugen Ruge’s novel In Times of Fading Light opens, the year is 2001, the place is a town named Neuendorf on the outskirts of Berlin—a town formerly in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), the Communist eastern half of Germany—and the characters are forty-seven-year-old Alexander Umnitzer and his aged father, Kurt. Still living in the decaying home where Alexander grew up, Kurt was once a prominent historian in the GDR. But by 2001, Kurt has trouble remembering how to eat his goulash and red cabbage with a fork. His language is almost entirely lost except for the word yes. Alexander, as he sits in his father’s study at his tiny desk, looks at the bookshelves and observes that the scholarly books and articles Kurt wrote “occupied a total expanse of shelving that could almost compete with the works of Lenin: a meter’s length of knowledge. . . . And now all of it, all of it was wastepaper.”

Just as Kurt’s GDR historiography is relegated to the waste bucket, the GDR’s former citizens fear—even today, twenty-five years after the fall of the Wall—that others perceive their lives lived under the GDR regime as “wastepaper.” It is hard to imagine anyone wishing the repressive regime of the GDR were still extant; yet there is a nostalgia, called “Ostalgie,” for some aspects of life in the former East. The GDR soda Vita Cola has been revived; the Osseria in Berlin is one of many restaurants catering to those longing for GDR food; politicians who grew up in the GDR point to its achievements in full employment and childcare. Scraps are being rescued from the waste bucket.

In Times of Fading Light does its part by illuminating forgotten GDR lives. It is not a nostalgic book. Nor, however, is it a book that portrays the GDR’s demise as the solution to its characters’ problems. Significant events in GDR history—for example, the building of the Wall, proclaimed by the regime to be an “anti-fascist protection wall,” in 1961, and the expulsion or house arrest in 1976 of dissidents such as singer-songwriter Wolf Biermann and chemist Robert Havemann—appear on the edges of the story instead of at its heart. Ruge coaxes empathy for his characters from us, not by bludgeoning us with the horrors they endure, but by depicting his characters with honesty, humor, and an acerbic tenderness as they navigate between family dramas and the state. This is the story of how a family lived, not how it suffered, under the regime.

The novel follows four generations of a GDR family over the course of fifty years, from 1952 to 2001: Wilhelm and Charlotte Powileit, ardent Communists who spend much of the Nazi era in exile in Mexico until they are asked by the Party leadership in 1952 to return to take up functionary positions in the newly founded GDR; Charlotte’s son Kurt Umnitzer—sent by his mother and stepfather to the Soviet Union as a young teenager, then interned in a Soviet labor camp near the Urals for criticizing the Hitler-Stalin Pact—who comes to the GDR in 1956 with his Russian wife, Irina, and young son, Alexander; Alexander, the book’s central character, a playwright; and Alexander’s son, Markus, born in 1977.

Their stories are told in three alternating, subtly interwoven strands. The first strand, told entirely from Alexander’s perspective, plays out in the fall of 2001 after Alexander, informed that he has inoperable cancer, decides to travel to Mexico, searching for traces of his grandparents’ years in exile. In the second strand, the novel skips from 1952 ahead in time, each episode lifting a curtain on another year in the intimate life of the family, each illuminating an era of the GDR, each masterfully told in a different family member’s voice. In 1959, for example, we hear Alexander as a four-year-old, contemplating everything from infinity to the smell of his own shit to his fear that his mother will be arrested for forgetting her milk coupon when they buy milk at the local co-operative store. And in 1995, we hear the voice of Alexander’s eighteen-year-old son, Markus, going with friends to a cellar club in what once was West Berlin, dancing and taking Ecstasy, hanging out with “hoolies,” attending his grandmother’s funeral, and through it all trying to figure out what his own life is and will be.

The novel’s third strand focuses on one day: October 1, 1989, grandfather Wilhelm’s ninetieth birthday, when he is feted by family, neighbors, and party functionaries. Each of the six sections devoted to that one day is narrated by a different family member. Here, for example, Irina anticipates the party:

Every year [Wilhelm] was awarded some kind of medal. Every year a speech of some kind was made. Every year the same bad cognac was served in colored aluminum goblets. And every year, or so it seemed to Irina, Wilhelm was surrounded by even more sycophants; they increased and multiplied, a kind of dwarfish race, all of them small men Irina couldn’t tell apart, in greasy gray suits, laughing all the time and speaking a language that Irina really, with the best will in the world, couldn’t understand.

Wilhelm is the family’s greatest champion of the GDR and the book’s greatest fraud. He sees the GDR’s history as a triumphant progression and presents his own position within the German Communist Party of the 1920s and 30s as an exalted one. However, on the day of his ninetieth birthday, the only interaction Wilhelm remembers having with Karl Liebknecht, the great martyr of the early Communist movement in Germany, is that Liebknecht told him, “Boy, blow your nose.” Even as Gorbachev is introducing glasnost and the Wall has begun to crumble, the birthday of a Party stalwart is still celebrated with tedious pomposity, and Wilhelm sings, “The Party, the Party is always right.” In this third strand, we do not hear Alexander’s voice. Alexander, the family finds out that day, has fled to the West, a mere month before the Wall falls.

The idiosyncratic voices of the various characters and the direct, colloquial prose of Ruge’s German are ably captured by Anthea Bell’s translation. Yet it is not quite flawless. As is perhaps inevitable, some nuances in humor and in language use disappear in translation. To cite an example from the first page of the novel: “New buildings that looked like indoor swimming pools, called townhouses.” It’s hard to picture a building that is something between an indoor swimming pool and a townhouse. The German “Schwimhalle” is a natatorium, a municipal swimming facility; the German “Stadtvilla” is not a townhouse but a term used, most likely by real estate agents, to describe a newly built, freestanding house that dreams of being described as a villa. Cross that wannabe villa with the natatorium, and you get the image, and its absurdity, that Ruge was intending. Still, Bell has done English readers a great service in translating Ruge’s novel and thus allowing us to listen to the different voices and see the details that make up their GDR lives. It’s the voices and details that make the novel come alive.

Although the novel does not read at all like a memoir, it is based on elements of Ruge’s own family history. Like Charlotte and Wilhelm, Ruge’s grandparents were Communist Party activists who spent years of exile in Mexico until they came to the GDR. Like Kurt, Ruge’s father Wolfgang was interned in a gulag in the USSR, then returned to Germany with his Russian wife and child in 1956 to become one of the GDR’s most productive historians. And like Alexander, Ruge himself wrote for theater and defected to the West.

“Why,” an audience member asked Ruge when he spoke at the San Francisco Goethe-Institut in October 2013, “didn’t you write a more purely autobiographical novel?” Ruge replied that there were three reasons: because he didn’t want to be judgmental of his characters; because of the gaps in his knowledge of his own family’s history; and because fiction allowed him to make the story more dramatic. To illustrate this, he talked about how both his father and uncle were in Soviet gulags as young men; although it was statistically very unlikely, both survived and returned to Germany. In the novel, however, Ruge has Kurt’s brother Werner die in the gulag, an event that determines who both Kurt and his mother Charlotte are. “Invention,” said Ruge in San Francisco, “is more true than the truth.”

In Germany, where the book was a bestseller and the winner of the 2011 German Book Prize, In Times of Fading Light is sometimes compared to Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks. A review called “The Fall of the House of Ruge” appeared in the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, (August 26, 2011), playing on both the title of Poe’s short story and the subtitle of Buddenbrooks: The Decline of a Family. Iris Radisch, book critic for the prestigious Die Zeit weekly newspaper, called Ruge’s novel the “great GDR-Buddenbrooks,” (October 11, 2011). In some ways, the comparisons to Buddenbrooks and even the novel’s own title are misleading. This is not merely the melancholy story of a family’s decline. Although the GDR’s lights have been snapped off, the light in Kurt’s mind has gone, and Alexander watches the fading light as the sun sinks over the Pacific in Mexico at the novel’s end, it is also the story of how a family continues. It continues under the oppressive GDR regime and through disappointments and sorrows after the fall of the Wall. It is the story of how a family lives on, despite, and perhaps because of, all its infidelities and human frailties, hilarious trivialities and absurd convictions, stupidities, and fraught relationships. The novel demands of us, its readers, to consider these lives as more than “wastepaper” and to see that there is something worth remembering in this complex and very human interplay between individual lives and their historic era.

About the Reviewer

Lisa Harries Schumann lives outside Boston and is, among other things, a translator from German to English, working on texts whose subjects range from penguins to poems by Bertolt Brecht and radio shows by Walter Benjamin, collected in the recently published volume "Radio Benjamin," edited by Lecia Rosenthal.