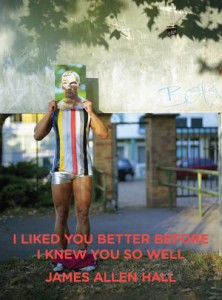

Book Review

James Allen Hall’s nine essays that make up his book I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well benefit from both total honesty and a strong and playful use of language. Hall’s voice sounds thoroughly authentic, even as he shifts tone, mood, and topic. Reading this work gives the reader an uncanny sensation that Hall is not just presenting essays about the events of his life, but also mapping the typology of his soul.

James Allen Hall’s nine essays that make up his book I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well benefit from both total honesty and a strong and playful use of language. Hall’s voice sounds thoroughly authentic, even as he shifts tone, mood, and topic. Reading this work gives the reader an uncanny sensation that Hall is not just presenting essays about the events of his life, but also mapping the typology of his soul.

Take, for example, the first essay, “My First Time.” Hall relates the first time he is called a “faggot” in school. Lulled into thinking that two other high school students are also gay, Hall, who professes to have been “sixteen, overweight, [and] miserably, effeminately gay,” is betrayed by his two “friends.” Hall is shoved by a fellow student and called the name, and spit from the malefactor’s mouth acts as a “glue to make the name stick.” This is the first time he is singled out as gay. He writes, “I felt the cuts all over my body where the word made invisible grooves, where the label was being sutured to my skin.”

In “The End of Terror,” Hall is in college, and exploring the gay scene in Orlando’s red light district for the first time. He witnesses explicit sex between men: “Men on all fours, heads bowed. Hairy men shaved down, the body corrected. Kneeling down. . . . Men holding other men by the jaw, pinching the nose closed so the mouth will open. Men lurching into other men, men receiving them.” For Hall, this sight is a revelation: “This is power: each man is giving in, burning off his shame as he surrenders to another man’s fantasy.”

Hall’s guilt and fear over his sexuality drive him “to be degraded. I wanted to pick up from the ruin the parts that remained whole.” Eventually he finds a man named Brandon. Hall lets him “tie me up. He binds my wrists with silk ties to his headboard.” The experience of controlled degradation is not wholly negative or positive for Hall. He explains:

Sex hurts. My stomach twists itself into knots with the quick jabs inside me. . . . After a while I discover a place inside the pain that feels almost-good, just when the momentum stills—he’s not pushing forward or drawing out, there is no torque. It’s a place where the membrane is thinnest, where the searing quality threatens to hurt you, but then you feel it lessen, release its hold. That’s where people like me live during intercourse.

Hall astutely maneuvers us toward the deeper levels of his struggles—not only growing up gay, but also his mother’s drive to self-destruction detailed in “Suicide Memorabilia.” Hall notes that “people try to die. They try and try.” Hall’s mother is such a person. She is scared. Hall writes: “We knew that once, as a girl, my mother woke from sleep because she could not breathe, woke to her father’s lips pressed to hers.” Her hands chronically shake. “The shaking always said, Look what you’re doing to me. The shaking always meant, Now you’re molesting me.”

Hall’s mother is not at all suited for motherhood. She tells her small children things they should not know: “You know… your father is awful in bed.” She is always leaving with other men while her husband awaits her return. She has an affair with a married doctor in Daytona Beach, then with a police officer who picks her up at her home in the cruiser. She lives with a man in Jacksonville whom Hall calls “Mr. Panties after finding out he likes to cross-dress.”

After many years, her suicide attempts increase and became nearly routine to Hall and his family. On one occasion his mother “took pills as my father watched. Thirty sleeping pills.” But this attempt “ends like all the rest . . . enveloped in terror, counting the pills as they slip out of her throat into the toilet.”

In “My AIDS,” Hall examines what it is like to be a gay man when AIDS is no longer a death sentence. AIDS is still a danger to the gay community, but unlike during the 1980s, there is widespread knowledge about prevention and treatments to slow down the progress of the disease. Hall takes ownership of the idea that he may contract AIDS, even while he feels that by admitting to the chance of getting the disease shifts him to another existential category. “By coming out, I admit to decay. I am admitted to the time-honored ‘risk-group’—that neutral sounding, bureaucratic category which also revives the archaic idea of a tainted community that illness has judged.”

Yet Hall lives in a world without the disease. “I don’t know anyone whose death resulted from AIDS. I have never been The Friend when someone tests positive.” He is from another generation of gay men. “When I came out in college, and the guys in the dorm posted a sign . . . of two stick figures fucking that read AIDES kills fags dead, I was more upset at their misspelling than the implication that I had or would have AIDS.” He later writes, “I wanted AIDS to belong to me. How sick am I?”

Despite the fraught nature of these essays, Hall handles the topics deftly, with a sly sense of humor. He is wholly aware that some events he relates are so dysfunctional that they become absurd. That Hall is able to invest humor into his essays saves them from unremitting gloom. He is a writer skilled enough to intuit the tone required to reveal the trials of his family, while at the same time inviting his readers into his stories with a sense of informality and ease. This is no easy task, especially when we consider the topics Hall tackles. This is what makes I Liked You Better Before I Knew You So Well an accomplished series of essays. Hall walks the fine line between doom and hope, and never falls.

About the Reviewer

Eric Maroney has published two books of nonfiction and numerous short stories. He has an MA in philosophy from Boston University. He lives in Ithaca, New York, with his wife and two children and is currently at work on a book on Jewish religious recluses, a novel and short stories.