Book Review

Our expectations about what a book is and might contain are constantly evolving. In our current century, readers encounter traditional volumes, tactile texts bound with front and back covers, as well as more ephemeral e-books, texts we read on screens, whose words disappear and are replaced when we “turn” a page. A book of poetry may certainly take either of these forms, but Jennifer Sperry Steinorth’s newly released Her Read: A Graphic Poem demands a specific attention from readers: it requires readers to consider the book not merely as a container for text, but also to think of the book as a meaningful object in and of itself. Sperry’s volume clearly belongs in the emerging canon of literary erasure; Her Read also impressively interrogates and complicates our understanding of the possibilities of this form.

In Her Read, Steinorth works on multiple levels. Her Read is a feminist, visceral, humorous, visual, considered, and nuanced revisioning of Herbert Read’s The Meaning of Art, “found at a library discard sale.” As she dives into her source text, Steinorth doesn’t hide herself—author of this re-envisioned text, poet, bodily inhabitant of the contemporary world—but instead foregrounds the self as she modifies, operates upon, uncovers, removes, defaces, and supplements both language and image. Literary erasure projects sometimes feel like they focus on the surface of the page, but Steinorth’s volume excavates depth: the more pages we read, the deeper we are allowed go.

As an object, Her Read is beautifully made and visually clear in its intentions. Steinorth’s hardbound cover presents embroidered, beribboned embellishments that obscure the source text’s title and author while foregrounding the red cloth of the original binding. Small, dark droplet stains on the front and back covers could be wine, or they might be blood. Combined with the presence of needlework, these mysterious stains invite readers not only to wonder what the covers might contain but also to think about what is pierced, about alteration through pain or puncture.

This book is thick; it has heft. Her Read includes roughly two hundred altered pages from The Meaning of Art, plus introductory, explanatory, and acknowledgement notes. This book materially differs from other recent erasures, like Jen Bervin’s Nets (2004, a grayscale erasure of Shakespeare’s Sonnets) or Mary Ruefle’s A Little White Shadow (2006, a white-outed facsimile of a 1889 novella by the same name) which are smallish, pocket-sized volumes. Approaching Her Read feels most akin to encountering Tom Phillips’s 1970 art book, A Humument: A Treated Victorian Novel, an almost four-hundred-page volume that has since been revised in multiple editions; Phillips’ vibrant, painted pages present snippets of text—words and letters—from the original novel. Similarly, Steinorth uses correction fluid, ink, paint, and thread to obscure or reveal text. Her color palate is subdued, with shades of tan, gray, and dusty yellow most prominent. Unobscured words are present on almost every page and are generally easy to discern. Sometimes background text, presented as visual chatter rather than foregrounded as part of a poem, is also available to the reader. Readers can make out traces of words like “decoration,” “checker,” “confused patterns,” or “knotted” through the tan and white paint covering the top two-thirds of page 120; the phrase “two birds // and / three children in the furnace” is fully revealed and stands out from the gray and white paint on the bottom third of the page.

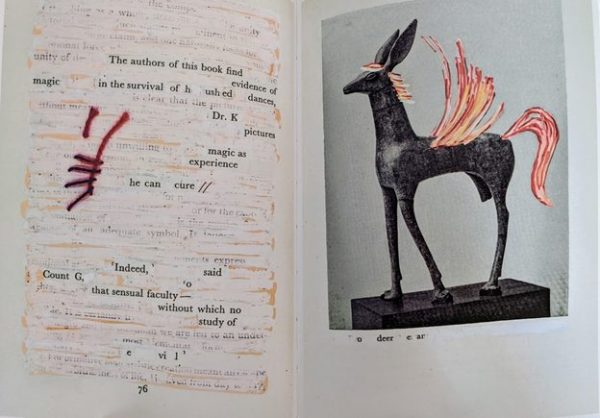

Steinorth retains the images of paintings and art objects that appear in the original text, often making droll deletions or additions. She uncovers the phrase “Distort / the given world” just above the image of an antique vase with mustache drawn on; crude breasts are hand drawn on a later photograph of a similar vessel. “I eat wood // such a Ho” is offered as a title for an image we recognize as Katsushika Hokusai’s The Great Wave. Red and orange painted wings, tail, and a short mohawk are added to a deer figurine; below, Steinorth’s caption reads “o deer e ar,” conjuring a reference to “derriere” in readers’ minds. Steinorth paints a circus animal’s traveling cage, complete with bars and small wheels, to contain and present a nonthreatening looking decorative metal cat. On page 162, Steinorth draws miniblinds, complete with pulleys, to partially obscure a grayscale landscape.

In addition to painting and drawing, Steinorth adds three-dimensional-looking sewn elements to her pages, including lines, Xs, French knots, sutures, and chains. These embroideries suggest women’s work, certainly a background theme of the text—this is Her Read, after all, not His. (“Exactly zero women are included in early editions of The Meaning of Art,” Steinorth reminds us.) Such sewn elements effectively highlight the materiality of the page. On page 207, a stitched line in sunset-colored thread traces the right margin; we turn the page to find a sunset-colored stitched chain in the corresponding left margin. Readers are reminded to think of the page not just as surface, but to remember the page is an integral part of—and cannot be separate from—the book.

While Her Read is a beautiful and enticing “graphic poem,” it also feels like more than a literary project. The volume feels personal, meditative, angry, and honest in unexpected ways; at times encountering Her Read feels most similar to surreptitiously reading another’s scrapbook or book of days.

Steinorth’s themes include retelling and transformation, the body and the book, love, reflection, and knowledge. Pain, though, is the true through-line: “pain / is / faithful,” Steinorth writes; “pain may be / the con / sequence.” There is “enthusiasm for pain” and descriptions of how “we are” “made // in pain to pose // and shimmer.” The world is in pain, animals are in pain, and the narrator is in pain. Pain is women’s pain:

I

remember a pain

that he

called

‘fine’

Too, the pain of living within domesticity is highlighted:

c an s

of

Tu n a

s a l a d

and

a woman who

went mad d e t a c h

ing all

h e r s

k

i

n

What appears to be a bloody fingerprint on page 7 (“My DNA is grafted to the body of the text, cells fixed with glue and correction fluid,” the author notes) encourages readers to conflate the author and the referenced “woman.” Perhaps modifying and excising language is its own type of madness. In her introduction, Steinorth describes erasure as “a violence, like falling in love,” and the book as “my little wound” or “an embroidered wound.”

Ultimately, Her Read presents a thoughtful, ongoing, and layered criticism of the source text and its implications as an early definitive volume of art criticism; it examines and questions patriarchy and privilege. Impressively, the volume also acknowledges the writer’s own preoccupations and potential blind spots. “This book is cut from. . . trauma and grief,” the author tells us early on. If anything, Steinorth’s work in Her Read is perhaps too self-aware; the author is always simultaneously writing and interpreting. This, though, is one of the true excitements of literary erasure: evidence of the poet working at the seams of reading and writing, highlighting for readers the beautiful and perilous stress that accompanies literary participation and creation.

About the Reviewer

Genevieve Kaplan is the author of (aviary) (Veliz Books); In the ice house (Red Hen Press); and four chapbooks, most recently I exit the hallway and turn right (above/ground press). Her poems can be found in Third Coast, Faultline, Denver Quarterly, South Dakota Review, Posit, and other journals. Genevieve lives in southern California where she edits the Toad Press International chapbook series, publishing contemporary translations of poetry and prose. Find her online at https://genevievekaplan.com/