Book Review

In “Paranoid Chant,” the closing track off Minutemen’s first EP, Paranoid Time (1980), a fuzzed-out punk riff opens up to bassist Mike Watt’s deep, screechy vocals, but for some reason the engine won’t start, as Watt, twenty-three and Cold War-raised and jaded, just can’t stop “thinkin’ of World War III!” He tries to get work done, tries to talk to girls, even the “six o’clock news makes sure [he keeps] thinkin’ of World War III!” The song is short. It climaxes, bubbles over in a minute’s time, with Watt wailing “Russia! Russia! . . . Paranoid! . . . Scared shitless!” And then it ends, leaving listeners baffled, befuddled, wondering to themselves, Is this a way to live? Or better yet, Is this the life I’m living, too?

In “Paranoid Chant,” the closing track off Minutemen’s first EP, Paranoid Time (1980), a fuzzed-out punk riff opens up to bassist Mike Watt’s deep, screechy vocals, but for some reason the engine won’t start, as Watt, twenty-three and Cold War-raised and jaded, just can’t stop “thinkin’ of World War III!” He tries to get work done, tries to talk to girls, even the “six o’clock news makes sure [he keeps] thinkin’ of World War III!” The song is short. It climaxes, bubbles over in a minute’s time, with Watt wailing “Russia! Russia! . . . Paranoid! . . . Scared shitless!” And then it ends, leaving listeners baffled, befuddled, wondering to themselves, Is this a way to live? Or better yet, Is this the life I’m living, too?

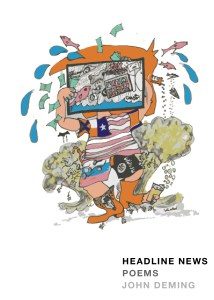

John Deming’s Headline News, an unfurling of calamity, dizziness, and confusion, operates within a similar landscape, its central question being, what is one to do with all this news? And news, at that, delivered straight from the phone and into the nervous system, like an IV drip of all things shock-and-awe, culminating with the Trump presidency. But not to fear, Deming reminds us, “I still have my Duane Reade / Rewards card I’ll be fine.” Much of the book reads in this type of light: Deming uncovering the news, digesting the news, then reacting accordingly, often with mordant metaphors (“the Titanic will always be sinking / no one knows you were alive”), witty candor (“you’re dirty the moment / you take money for a job”), and a sense of levity to which the chronically aware have become inured.

A crucial component of the book’s success involves the meticulous balance Deming constructs between disarray and order, which holds a mirror to the goings-on of the world: yes, the headlines are clear, but how did we get here? As the poet seeks to answer this question, his stark ruminations propel the narrative, which, akin to the endless scroll of Twitter or Facebook, darts from subject to subject, at times jerking and jostling the reader, but this seems to be the book’s intent—to serve as the literary approximation of a late 2016 news-watching bender, a rollercoaster that gets faster, worse with age, and leaves your neck stiff in the morning. Thankfully, the book’s structural base is a pillar on which the reader can lean, for each poem’s nexus is its length (every page, ten lines each) and gimmick (built into each poem is an actual news headline, denoted in all caps). Some poems begin with a headline; other times, the headline weaves its way into the poem, functioning as the punch line or setting up an end rhyme:

I’m plasticene

I’m plastic

my debts exceed

my assets

got the need and latitude

for depression medication

TOP DOC: MEDIA BIAS

ON ANTIDEPRESSANTS

‘ASTOUNDING’

amazing

As a supplement to Deming’s linguistic deftness, his content choice—anxiety, depression, and isolation—imbues the book with a jumpiness that, in the age of waning attention spans, feels all too familiar. As poet Andy Mister once wrote, “We don’t want writers to tell us about their lives, we want them to show us something about our own.” Thus, like any good poet, Deming doesn’t wallow in his ailments or prove that his suffering is above the reader’s. Instead, he serves as both mentor and friend, reminding us that we’re crazy only insofar as we’re living in an unmanageable milieu, where “the editors are read more than the reporters / because most people just read the headlines.” Deming, a former journalist himself, seems to ask at times, Is anybody listening to me? Am I shouting down a well? But there are people listening, and sometimes we meet the people who flutter into and out of the poet’s life and mind, if only fleetingly; and while their sojourns are short, their anecdotes demonstrate Deming’s conscientiousness. There’s Ashley, whose “jewelry line was called Missfits / she made them by hand,” and Crystal, who “doesn’t like Ambien / because a giant eye closes / around her head.” And then there’s Deming’s unnamed lover, whom he invokes from time to time, but who never seems to answer her phone. “Let’s chain-smoke on the fire escape,” he implores, “and fall in love again / it’ll be easy.”

But things are never that easy, and sometimes the world—and its media and ilk—are too much to take. As such, some of the book’s most resonant moments occur when Deming rejects the trappings of external life and absconds, instead, to his interior life, where the TV’s on and turned to ’90s sitcom reruns. In one instance, the poet recalls a scene from cult classic My So-Called Life, which earned an immediate dog-ear:

CLAIRE DANES DEBUTS RED HAIR,

TALKS MEETING OBAMA ON ‘LATE SHOW’

I’m never not going to be

Angela Chase sitting on her bed

listening to the Cranberries’

“Dreams” then her mom comes in

and turns it down

Angela says just turn it off

Patty replies no

I like it

This poem! What’s so striking and poignant is Deming’s grasp on the fragility of human relationships, and that, even if the reader hasn’t seen this scene or isn’t at all familiar with the show’s characters, a message can still be gleaned from this interaction: a mother precariously setting boundaries while trying not to isolate her daughter. A metaphor for the poet’s life? The journalist’s? This poem stands out to me on a personal level, for when I go to the suburbs to see my parents, I’ll inevitably end up playing music on my laptop while doing my laundry, at which point my mother or father will QUICKLY instruct me to ‘shut my door’ or ‘just go back to Jersey City already!’ So then, when I eventually do, I’ll get that text from my mom or dad asking “who was singing that song about wanting to go out but wanting to stay home?” (A: Courtney Barnett). In those small, deeply human moments, you realize that you are essentially your parents—or have at least inherited some of their aural proclivities. And as much as they want to be left alone, they do want to connect with you, learn from you.

All things considered, the richness extracted from Headline News exceeds the length of a reasonable review. However, it’s vital to note that as the book progresses, Deming’s criticism becomes more pointed, acerbic, and antiestablishment. Ultimately, it’s neoliberalism, hyperconsumerism, and Clinton-era media deregulation that’s left us with this mess. However, the book doesn’t quite spell it out like that, but it makes us want to find out how we got here, why “the rational ethics of listening well / and defending only researched opinions / should be obvious at this point,” and yet, alas, aren’t. Through a well-balanced blend of skepticism, media literacy, and a fondness for the human connections that happen away from the screen, John Deming delivers a heady punch of poetry, social criticism, and an instructional guide for how best to navigate and negotiate the headlines.

About the Reviewer

Scott Wordsman’s recent work has appeared in the Rumpus, THRUSH, Forklift/Ohio, Coldfront, and elsewhere. Last year he received a nomination for Best New Poets.