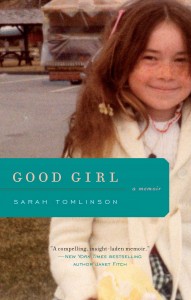

Book Review

Sarah Tomlinson’s debut memoir, Good Girl, is about her complicated relationship with her narcissistic, often absent father. From the outside, Tomlinson had a picturesque childhood. Born in 1976, she was a bright, precocious child who grew up with her mom, stepfather, and little brother on a hundred-acre rural enclave in Freedom, Maine. Still, she longed for her birth father, an acid-dropping, mystically “enlightened” itinerant taxi-driver her mother had divorced because he was a compulsive gambler. As a young girl, Tomlinson looked forward to her father’s sporadic visits. She often stood alone by the window for hours, waiting and waiting for her father to arrive. Most of the time he failed to show. She reflects on the speculative calculations she performed as she stared toward the empty road:

Sarah Tomlinson’s debut memoir, Good Girl, is about her complicated relationship with her narcissistic, often absent father. From the outside, Tomlinson had a picturesque childhood. Born in 1976, she was a bright, precocious child who grew up with her mom, stepfather, and little brother on a hundred-acre rural enclave in Freedom, Maine. Still, she longed for her birth father, an acid-dropping, mystically “enlightened” itinerant taxi-driver her mother had divorced because he was a compulsive gambler. As a young girl, Tomlinson looked forward to her father’s sporadic visits. She often stood alone by the window for hours, waiting and waiting for her father to arrive. Most of the time he failed to show. She reflects on the speculative calculations she performed as she stared toward the empty road:

As I waited for him to arrive, I rested my fingertips on the wood of the windowsill, staving off my fear of disappointment by redoing the numbers in my mind. At two, when he had still not come, I held onto the logic of my math problem: if he left at eleven, he’d be there by two thirty. But no, just to be safe, maybe he hit traffic, or got his cab serviced, or grabbed a fish sandwich on Route 1.

Tomlinson’s story tumbles forth with the rapid urgency of a young woman searching for meaning and perhaps a bit of insight amid the chaos of unexpected wounds created by her neglectful, self-centered father. As a teenager she was smart and ambitious, seeking more than her small high school and her bohemian home life could offer. At age fifteen she left for Bard College at Simon’s Rock before going on to earn a graduate degree and establishing herself as a journalist, music critic, and ghost writer. Throughout her travels to Boston, Portland (Oregon), and Los Angeles, she struggled to negotiate work, love, and friendship. With intelligent and courageous writing, Sarah Tomlinson refuses to dilute the painful realities of her life—the trauma of a school shooting, the social lubricant of drugs and alcohol, the choice of unavailable men. Tomlinson examines her life through a dual lens: one tinted by her inner child’s belief that her personal value is rooted in external validation and the other a clear lens of the grown writer who recognizes her personal value rooted inside herself.

For an author, father-daughter memoirs can be tricky business. Confronting fathers directly and publicly is not easy. To write about a father is to sit in judgment upon him. Not only do cultural norms dictate that such judgments are a no-no, but an author-daughter still hopeful of paternal reconciliation has personal, after-publication fallout to consider. She might ask herself what she’s trying to work out on the page, how her story reveals insights about herself, what readers might gain from those insights, and whether her private-made-public revelations might affect her relationship with her still-living father. Not an easy list of considerations.

Although the absentee father-daughter conflict is a familiar theme in the larger landscape of memoirs, what is unique and perhaps most engaging in Good Girl is Tomlinson’s honest depiction of how her father’s unavailability shaded almost every aspect of her childhood, teenage, and young adult life. Tomlinson’s prose is strongest when she dives into close observation of her father’s everyday behavior. With subtle humor she captures his delusional revelry and childlike exuberance as he visits her two-story Boston apartment for the first time:

He was halfway across the warped kitchen floor when he stopped, transfixed by the view of the treetops and sky straight ahead. He put both hands out as if to steady himself on a surfboard, bent his knees slightly as if testing the give.

“Far out,” he said.

At its heart, this book is a coming-of-age story about the emotional cavern created by her father’s absence. Tomlinson strives to work around, if not repair, the internal damage her father did. On one level, she continually tries to deepen her connection with him—she really does want to have a relationship with her father, shortcomings and all. On another level, she comes to realize that in order to protect the newfound sense of wholeness she’s strived so hard to achieve, she must keep her father at arm’s length.

Good books sometimes remind us of things we already know on some level. We know that people are complicated; we know that daughters can love fathers despite their shortcomings; we know that a wounded heart can crawl back to its source of pain time and again; and we know that there may or may not be an adequate response to a child’s call for parental attention. In the end, Tomlinson finds no tidy solutions. She does, however, leave readers with the glimmer of hope that some sort of peace is possible, even if it means we continue to love unconditionally the people who have disappointed us.

About the Reviewer

Carole Firstman is the author of Origins of the Universe and What It All Means: A Memoir (Dzanc, 2016). Her work has been noted in the Pushcart Prize and Best American Essays.