Book Review

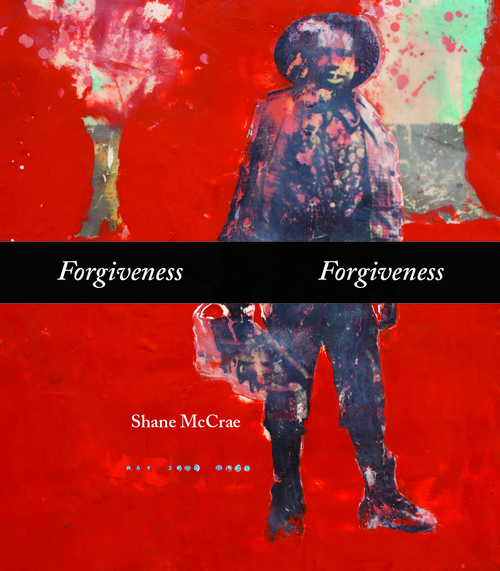

In his new collection, Forgiveness Forgiveness, Shane McCrae engages representations of racial tension in American print culture, presenting spare, haunting lyrics that prove to be as beautifully rendered as they are disconcerting. Focusing on the 1940s children’s book, Stories of Little Brown Koko, McCrae poses several compelling questions to the reader: What larger structures of power and authority govern representations of racial difference? When are we first told how to see others (and told how we ourselves are perceived)? How is the gaze of other communities refracted and internalized? As McCrae teases out possible answers to these questions, his new book offers technical choices that are as resonant as they are subtle, offering readers a perfect matching of form and content.

In his new collection, Forgiveness Forgiveness, Shane McCrae engages representations of racial tension in American print culture, presenting spare, haunting lyrics that prove to be as beautifully rendered as they are disconcerting. Focusing on the 1940s children’s book, Stories of Little Brown Koko, McCrae poses several compelling questions to the reader: What larger structures of power and authority govern representations of racial difference? When are we first told how to see others (and told how we ourselves are perceived)? How is the gaze of other communities refracted and internalized? As McCrae teases out possible answers to these questions, his new book offers technical choices that are as resonant as they are subtle, offering readers a perfect matching of form and content.

With that in mind, McCrae’s use of enjambment proves to be especially striking as the collection unfolds. Frequently breaking the line at unexpected moments, McCrae uses enjambment to create a voice that is at once hesitant and insistent, that seems startled amidst the remnants of history, mass culture, and cruelty that surround him. McCrae’s artful use of enjambment seems especially fitting in the book’s opening piece. He writes in “The Subject”:

Little Brown Koko goes by Koko

in the book as I remember it

Although he is / Little and black although he is

Subject to the book

in the book as I remember it / Nobody calls him Little Brown Koko

nobody in the book

Here McCrae breaks the line in what might seem, at first glance, unlikely places, and chooses not to break the line where there appear to be natural pauses. For example, when reading the line “in the book as I remember it” aloud, one would likely pause after “book,” but McCrae deftly undermines the reader’s preconceived ideas about rhythm and cadence. By creating a series of almost unnatural pauses in the piece, McCrae hints at the speaker’s discomfort, his unease in even describing these representations of race in books that were meant for the very youngest readers. While the content seems matter of fact, offering an objective, almost scientific reporting of the book’s contents, McCrae’s subtle technical complicate the poem in provocative ways, opening up myriad possibilities for readerly interpretation.

Along these lines, McCrae’s use of fragmentation proves equally noteworthy as the book unfolds. The poems in Forgiveness Forgiveness present us with a speaker whose voice proves to be beautifully and poignantly fractured, suggesting that mass culture, and the images that circulate within it, have the power to shatter the very communities that they depict. Indeed, McCrae’s speaker can no longer situate himself within these conversations, as he is merely “subject” to them. In many ways, he suggests that we are subject to the identities that are imposed upon us by others, made to inhabit clothing that no longer (and has never) fit. He writes in “The Empty Spaces”:

Little Brown Koko skips along

A picket fence as tall as he is

in the book as I remember it

In the book as I remember

it the fence is brown

And I remember wondering

why it wasn’t white / Like

the white picket fences in my mind

What’s fascinating about this passage is the fact that McCrae makes ambitious claims about race and class through small stylistic choices. By including a dash in the line “why wasn’t it white / Like…”, McCrae ultimately asks us to consider the ways that our identities pieced together from various texts, artifacts, and images, none of which we retain any agency over. In much the same way that the line itself is pieced together, and gestures at its own fragmentary nature, the self is an amalgamation of cultural detritus, much of which we did not create ourselves, but rather, have inherited from others. Along these lines, McCrae suggests the myriad ways these pieces of found language and culture are internalized and unwittingly made into a normative standard (an idea that he communicates poignantly by stating that the speaker had imagined the picket fence as “white”) that the speaker also finds himself subject to. I’m intrigued by McCrae’s subtle and dexterous use of fragmentation and typography to convey these ambitious claims about culture. With that in mind, McCrae’s Forgiveness Forgiveness is a highly accomplished and moving collection of poetry. This is a stunning follow up to an already accomplished body of work.

Published 2/10/2015

About the Reviewer

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of twenty books, which include Melancholia (An Essay) (Ravenna Press, 2012), Petrarchan (BlazeVOX Books, 2013), and Scorched Altar: Selected Poems and Stories 2007-2014 (BlazeVOX Books, 2014). Her awards include fellowships from Yaddo, the Ucross Foundation, the Helene Wurlitzer Foundation, and the Hawthornden Castle International Retreat for Writers, as well as grants from the Kittredge Fund and the Elizabeth George Foundation. She was recently selected as a Visiting Artist at the American Academy in Rome.