Book Review

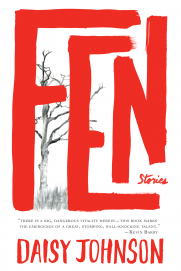

For a reader seeking a tidy collection of stories that mind their manners, Daisy Johnson’s debut collection, Fen, from Graywolf Press, is not that book. This is in part due to these stories’ magical and fantastical elements, but it would be a disservice to pigeonhole this collection as being weird exclusively on account of its being surreal. These stories, while inexplicable, are also quite ordinary and mundane in subject matter: sisters grow apart, there are first loves, a younger sister intrudes upon the established borders of sibling territory when she goes drinking with her older brother’s friends. But also within its pages, a house falls in love with a girl, but like real love, it’s complicated, and the house ultimately grows possessive and jealous. “Give a house half a chance and it’ll answer back.” This is a collection about sexuality, belonging, the unexplainable compulsion and magnetism toward chosen lovers. It’s also about pleasure, agency, consent, and the marginalized female body. In the opening story, our narrator’s sister intentionally starves herself into an eel. In another, women consume men—they’re potentially read as witches or vampires, we’re never able to pin them down for sure—but after the consumption of their latest victim, the men’s language exists within them like a virus they cannot shake. Magic is present in these stories, but it often feels like an afterthought, the static of background noise. Instead of drawing attention to itself, it is most often a mode for teasing out the emotional stakes of the characters.

For a reader seeking a tidy collection of stories that mind their manners, Daisy Johnson’s debut collection, Fen, from Graywolf Press, is not that book. This is in part due to these stories’ magical and fantastical elements, but it would be a disservice to pigeonhole this collection as being weird exclusively on account of its being surreal. These stories, while inexplicable, are also quite ordinary and mundane in subject matter: sisters grow apart, there are first loves, a younger sister intrudes upon the established borders of sibling territory when she goes drinking with her older brother’s friends. But also within its pages, a house falls in love with a girl, but like real love, it’s complicated, and the house ultimately grows possessive and jealous. “Give a house half a chance and it’ll answer back.” This is a collection about sexuality, belonging, the unexplainable compulsion and magnetism toward chosen lovers. It’s also about pleasure, agency, consent, and the marginalized female body. In the opening story, our narrator’s sister intentionally starves herself into an eel. In another, women consume men—they’re potentially read as witches or vampires, we’re never able to pin them down for sure—but after the consumption of their latest victim, the men’s language exists within them like a virus they cannot shake. Magic is present in these stories, but it often feels like an afterthought, the static of background noise. Instead of drawing attention to itself, it is most often a mode for teasing out the emotional stakes of the characters.

The landscape of the English Fenlands is ever present. Tonally, Johnson’s collection is reminiscent of another book that draws power from its lyrical rendering of the fens, Graham Swift’s novel, Waterland. Fen is atmospheric, liminal, and often ominous as the fens permeate each character’s experience. While there’s a great deal of water imagery, this representation of the fens often leans more toward cultural, rather than ecological commentary. Johnson plays with myth and folklore, but her play is not overwrought. These stories exist between the crags of monotony and the humdrum of everyday life. The ennui of these lives is presented through the lens of young women in lines like, “Virginity was a half-starved dog you were looking after, wanted to give away as quickly as possible so you could forget it ever existed.”

Simply put, Johnson knows her way around a sentence and continually pushes the boundaries of language so that we might marvel at its elasticity. She subverts the reader’s expectations at the sentence level with disarming images and metaphors that shift and morph, accumulating meaning as tracked throughout the collection. These are particularly strong when she’s depicting the body. In the case of women who hope to seduce men: “We shaved all the hair off our legs and underarms, plucked until we were smooth, coating the white bathtub in drag lines of dark; moisturised until we shone white and slick through the dim; painted crimson ‘yes’ markers on our mouths.” Later, the image shifts, “We painted her mouth a red church.”

Johnson is without a doubt lyrical, but she also moves beyond pretty sentences as she plays with the very concept of language in her stories. In “Language,” the words of a deceased husband physically hurt his widow: “…his words were in her system like a sickness. She could feel the spiky pressure of letters against her gut, the sticks of Ks and Ts and Ls on her insides.” In “Blood Rites” the women devour men and learn, “The truth was fen men were not the same as the men we’d had before. They lingered in you the way a bad smell did; their language stayed with you.”

Short stories are successful through omission. By definition, they need to be short, but within that limited space they must transmit narrative, while trusting the reader to intuit what has been left out. Johnson’s stories are not only sparse; they’re acute. Though these stories are dreamy and evocative, they’re also skeletal and rarely arrive at a singular capital-T Truth. Instead, a Johnson story will change the reader’s temperature, perhaps only by one degree, but it’s an unmistakable shift nonetheless. For many readers there’s a discomfort in this, in being asked to infer, to piece together. Johnson is assured in her withholding and makes her reader sit with that discomfort. This poetic coming-of-age collection is both strange and beautiful. We are pressed to pay attention as we read: stories are told in reverse, animals and humans merge, intimacy is forced through the use of the second person, and she doesn’t bother with quotation marks—in other words, we are asked to listen. Many of the characters feel numb, or like they’re moving through the world motivated by internal desires that they might never be able to articulate, and Johnson allows her reader to be swayed, and pulled along with the character. Johnson is a talent and a new voice to which we should all be listening.

About the Reviewer

Jennifer Popa recently relocated from the interior of Alaska to the South Plains of West Texas where she is in her second year as a Ph.D. student of English and Creative Writing at Texas Tech University. She's currently working on a collection of short stories, some of which can be found at Grist, Watershed Review, The Boiler, Monkeybicycle, and Fiction Southeast. She can be found at www.jenniferpopa.com.