Book Review

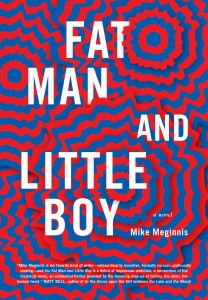

Mike Meginnis has done something truly remarkable with his debut novel, Fat Man and Little Boy. He has created a piece of art that transcends genre boundaries while remaining both accessible and conversation sparking. The novel is the personified tale of the bombs dropped on Japan during World War II that, upon their explosion, gave birth to the characters of Fat Man and Little Boy. Meginnis’s novel is historical fiction with a twist, a very sharp and weird twist: historical magical realism. The blend of history and absurdity is seamless, portraying real events alongside fantastically impossible ones in an unsettling and brilliant way.

Mike Meginnis has done something truly remarkable with his debut novel, Fat Man and Little Boy. He has created a piece of art that transcends genre boundaries while remaining both accessible and conversation sparking. The novel is the personified tale of the bombs dropped on Japan during World War II that, upon their explosion, gave birth to the characters of Fat Man and Little Boy. Meginnis’s novel is historical fiction with a twist, a very sharp and weird twist: historical magical realism. The blend of history and absurdity is seamless, portraying real events alongside fantastically impossible ones in an unsettling and brilliant way.

In a recent interview, Meginnis explained to me the inception of these characters: “When I saw those phrases again [Fat Man and Little Boy] it immediately made me sad because it seemed unnecessary to me to name them, as if they were people.” And that’s who he created: two immensely sad characters. Little Boy, being the older of the two, walks for days after the explosion to find his younger, though much larger, brother, and together they explore Japan. Not only do they witness the destruction they have caused, but also, oddly, they begin to cause natural objects to grow to epic proportions in their wake, much like you’d expect soil to be far more fertile after a volcanic eruption. After two Japanese soldiers become suspicious of their true identities, Fat Man and Little Boy move to France and assume aliases: John, the large uncle, and Matthew, the very young nephew. As they are still technically newborns despite what their bodies imply, the two must then grow, learn, and mature throughout their time in France, all the while concealing the horrible tragedies they have inflicted. They meet their greatest challenges as they work at a former concentration camp, turning it into a hotel under management of an American widow.

Meginnis uses growth as a powerful motif throughout the narrative in a literal, figurative, structural, and emotional way. Everything the brothers touch sprouts new life: mold on the food they eat, babies in the bellies of women they meet, a willow tree from the death of someone they try to save. This, however, is a cause of great distress, for they intuit that these newborn things know about their shady past, their destructive birth. Even infant pigs know the brothers’ history:

“Why do the little pigs know who we are and not the big ones?” says Fat Man. “And if they know us, then why do they love us?” He sets down his pig and looks at his black palms. “How can they love us?”

This self-loathing does not dissipate as the story progresses.

Despite their guilt, the two main characters nevertheless experience a significant amount of cognitive and emotional growth. At the beginning Fat Man knows nothing. Upon meeting his brother, he must learn even what happiness is:

”If that’s what it looks like, I guess you must be.”

Fat Man mirrors Little Boy’s expression to see how it feels. He tries variations. He touches his face.

“Happiness,” he says.

But Fat Man very quickly becomes the more intelligent of the two characters, first recognizing Japanese words, then becoming completely fluent in French without even seeming to try, as if this intelligence has just spontaneously happened to him. Little Boy, on the other hand, regresses in a very similar fashion, creating an interesting contrast between the two bombs. In the beginning, when the two are starving in the destruction they created, it is Little Boy who finds them money and must explain to his brother that money can be exchanged for food, but by the time they make it to France, Little Boy no longer speaks and eventually becomes an infant in his own right, making Fat Man feed, bathe, and put him to bed. The growth and regression in the characters seem to mirror the life and death drama that follows war. In order for some things to grow (a new town, for example, or even Fat Man), something else must be destroyed (the old Hiroshima or Little Boy). “That’s essentially what happened to Japan. We basically burned half of it to the ground and now it’s the economic and cultural powerhouse,” says Meginnis. This is something we see all over the world and in our own lives: some things must end in order for others to begin.

Even the structure of the novel reflects this focus on growth. In the first section of the book, the chapters are short, averaging between two and five pages. The sentence structures are simple and so is the vocabulary: “Two bombs over Japan. Two shells. One called Little Boy, one called Fat Man. Three days apart. The one implicit in the other. Brothers.” It tricks you into thinking that this 400-page novel is going to be a breeze, a quick read. And it is for a while. The transition is so smooth, the reader may barely notice that the chapters are now ten to fifteen pages long. The sentences become longer and more complex:

He goes on, in his meant-to-be-educational household mixture of English and French, describing what he imagines his brother keeps balled up in his mind like a fist: the memory of the Japanese family, the babies, the piglets, the fire, their trees. . . .

The novel ends with the last chapter taking up a whopping fifty pages in which every element—character, imagery, and structure—reaches its fullest potential; to say more would spoil the ending.

The greatest gift Meginnis gives his readers is the heartfelt insights, though dark at times, that make this book an incredible tool to spur discussion on many levels, and to help the reader experience personal growth. But these insights, even when presented as aphorisms, don’t feel like self-help advice, flowing instead naturally from the plot of the story. For example, the Japanese medium asserts: “The dead can’t see the dead . . . because it would be too much comfort.” At another point he says, “Sometimes the living are dead come back.” Little Boy has the realization that “in a wasteland you can look for food, water, or people. You can wait to die. You can assign the blame for what’s been done, or you can accept what it is and survive.” As Meginnis explains: “I did want to talk to the guilt that I feel and to what extent that guilt is valid. Obviously, I didn’t, myself, do it and neither did those bombs, themselves choose to do it. But I think we are complicit in the way that we have buried that memory since.” Taboo topics, such as death and war, are often the most important and, thankfully, literature like this is being written and published to facilitate just that dialogue.

Fat Man and Little Boy is unlike anything I’ve read. As a piece of art, it grows tremendously from inception to death in both content and form. Even the reader may experience a bit of growth by the final page. Enjoy this book for its philosophy, its character, and its uniqueness, but be willing to get a little bit uncomfortable. This is a book for readers open to a mental and spiritual challenge.

To read an interview between Malissa Stark and Mike Meginnis, click here.

About the Reviewer

Malissa Stark is a freelance writer from Colorado currently living and working in Chicago. Her book reviews have been published in Bookslut and The Review Lab as well as The Colorado Review. Her work can also be read in Eco News Network, The Story Week Reader, and Crack the Spine, among others. She also serves as associate editor of The Publishing Lab, an online resource for emerging writers.