Book Review

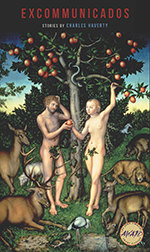

Charles Haverty’s Excommunicados is a collection of subtle and many-layered stories that defy simple categorization. There are some similarities of subject matter—inadequacy of fathers and husbands, failure of intimacy in couples, inevitable clashes between opposing cultures—but these are superficial similarities. The true constant in these stories is the form of pleasure they deliver. Haverty combines a satisfying weightiness of subject matter—painful shortcomings exposed and unflinchingly faced (though not necessarily resolved)—with a playful lightness in the telling.

Charles Haverty’s Excommunicados is a collection of subtle and many-layered stories that defy simple categorization. There are some similarities of subject matter—inadequacy of fathers and husbands, failure of intimacy in couples, inevitable clashes between opposing cultures—but these are superficial similarities. The true constant in these stories is the form of pleasure they deliver. Haverty combines a satisfying weightiness of subject matter—painful shortcomings exposed and unflinchingly faced (though not necessarily resolved)—with a playful lightness in the telling.

For example, in “Tribes” the lightness is quite literally comedy. A comedy writer claims to want to win back his estranged wife and devises a scam to get the money to do so from his wife’s unsympathetic brother. The writer’s son must decide if he wants to participate in his father’s scheme. The story is at heart about the son finally understanding how he fits into his family and journeying, literally and figuratively, from a place in which he desires to have more attention from his historically absent father to a place where he refuses to play a part in a script of his father’s making. Its poignancy is palpable. The story is, however, also leavened with a thread of humor in the form of the father’s one-liners (“The kid can hardly find the toilet, he’s going to explain the ins and outs of air travel?”) and the accidentally humorous statements of the non-English speaking cousin.

This symbiotic combination of the entertaining with the weighty is equally true of the other stories, and in each one the form of entertainment matches the tale. For example, in “The Angel of the City,” the second of three linked stories in the collection, a philandering husband has been ordered by his no-longer-tolerant wife to take a vacation in Venice with their two daughters. The story mainly recounts the husband’s repeated failures to understand and connect with the women around him because of his mistaken belief that his condescending appreciation is enough to make them love him. The reader can’t help but feel sorry for the protagonist even though he has brought isolation upon himself with his own obnoxious behavior. This story contains a dark humor that particularly fits the failure and lack of understanding embodied by the protagonist. For example, alone in a hotel room, husband and wife have the following exchange:

“If I were a woman, I’d be a lesbian,” he said. “I mean, how can any self-respecting woman not be a lesbian?”

“Then maybe I’ll have an affair with a woman,” she said. “For the sake of my self-respect.”

Similarly the protagonist also mistakes Stockholm Syndrome for Stendhal’s Syndrome, even though the former is clearly apt to the vacation he is experiencing. And throughout the story, the protagonist’s daughters get in their own zingers. One, who clearly knows of her father’s infidelity, quips over dinner: “How did you even manage to get [your prick] through customs?”

Haverty’s deft incorporation of thematic repetitions into his stories also makes them a delight to read. In “Crackers,” a story about a man making sense of his own identity by reconsidering a revelation about his grandfather, the bare facts of the protagonist’s history might have been story enough to tell. Seamlessly woven into the fabric of the central tale, however, are references to President Nixon—not merely as setting or historical context, although they do serve in that function, but also as amplification of plot elements and as a narrative catalyst for the unfolding of the story. Indeed, words from the protagonist’s bathroom encounter with the former president provide the only closure to the story. Catching all of the Nixon references (including investigations, impeachments, enemies, winners at all costs) in this story is a delight that stands on its own. Thus Haverty’s use of thematic repetition, or echoing elements, both enriches the telling of his tales and gives the reader the pleasure of making connections and noticing patterns.

Excommunicados is a collection to appreciate for its exploration of human existence and complex considerations of how humans make sense (or fail to make sense) of their own stories. And, with its many ways of making the telling entertaining, Excommunicados is also a collection to read for the sheer enjoyment of it.

About the Reviewer

Amanda Moger Rettig is a writer living outside of Boston with her husband and three children.