Book Review

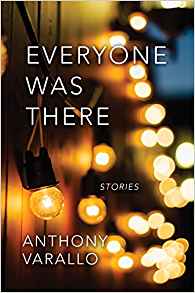

“I am simply not interested, at this point, in creating narrative scenes between characters,” Lydia Davis once claimed in an interview. So it is with Anthony Varallo, arguably a Davis devotee, in his new collection of short-shorts Everyone Was There. Like Davis, Varallo has little use for traditional narrative structures. Rather, the stories in this collection offer a critical examination of narrative as an artifact, drawing attention to its limitations as well as its versatility. These are brief meditations on the function of narrative, what we expect from it and why. As with so many writers of his ilk, Varallo crafts stories that are significant not simply for what is on the page but also for what he leaves out. This minimalist approach establishes a tone that is equal parts humorous and somber and challenges our general attitudes toward stories and their purpose.

“I am simply not interested, at this point, in creating narrative scenes between characters,” Lydia Davis once claimed in an interview. So it is with Anthony Varallo, arguably a Davis devotee, in his new collection of short-shorts Everyone Was There. Like Davis, Varallo has little use for traditional narrative structures. Rather, the stories in this collection offer a critical examination of narrative as an artifact, drawing attention to its limitations as well as its versatility. These are brief meditations on the function of narrative, what we expect from it and why. As with so many writers of his ilk, Varallo crafts stories that are significant not simply for what is on the page but also for what he leaves out. This minimalist approach establishes a tone that is equal parts humorous and somber and challenges our general attitudes toward stories and their purpose.

This is not to say that Varallo is uninterested in traditional creative elements like character, setting, voice, etc. Quite the opposite: he seems so preoccupied with them as objects that each piece tends to focus largely on one element over the others. The short-shorts in Everyone Was There bounce whimsically between realism, fabulism, and absurdism, invoking the work of authors like Donald Barthelme, George Saunders, and David Foster Wallace. In “Unfriend,” for instance, we follow an unnamed narrator as he is inexplicably besieged by an onslaught of loose acquaintances:

I escape to the men’s room, but my neighbor’s brother—the one who keeps sending me links to est conferences—is just finishing up at a urinal, while my father’s Al-Anon sponsor wrestles a paper towel from the wall dispenser…I head for the nearest stall, but my junior high yearbook editor is already inside, arms folded, staring me down with a clear look of contempt.

Varallo is interested in the sense of isolation that descends when our interconnectedness breaks down. To this end, there is little emotion in the book; most of the narrators speak matter-of-factly, eschewing sentimentality in favor of a focus on the mundane.

Similarly, Varallo’s work explores our relationship to the everyday objects that tend to define our lives. There is a degree of fetishization here that deftly illustrates our connections to them, as evidenced in “The Good Phone”:

We called it the good phone, the downstairs telephone mounted to the kitchen wall, to differentiate it from the only other telephone in our house: the green Trimline in our parents’ bedroom. If we were upstairs and the phone rang, we would race into the bedroom, dive across the bed and try to answer by the third ring—this, a game of our own devising, a game we sometimes expanded upon, assigning meaning to the third ring, as in, If we don’t answer the phone by the third ring, the world will explode. The Trimline had illuminated buttons that glowed as greenly as fireflies. But the caller always sounded like they were trapped inside a tin can.

Here, Varallo’s focus on the phone over the “we”—who is never named, never given any sort of identity in the piece—drives home the fact that we are, to a larger degree than most of us would like, the stuff with which we tend to surround ourselves.

Running through all these stories is a thread of humor that reminds us of storytelling’s inherent silliness: we invent narratives to help us understand a world unfettered by meaning. Perhaps this is why very few of Varallo’s stories offer the kind of resolutions readers have come to expect from literary fiction, because the tidiness of those narratives undermines the absurdity of our day-to-day lives. He isn’t creating realistic worlds for us to traverse; his worlds are like plywood sets with only the most incidental resemblance to reality, spoofs of what we have come to expect from fiction. In “The Pinball Speaks,” we become attendees to a speech given by, yes, a pinball:

You’ve asked me how I feel about being a pinball, an odd question, sort of like asking how you feel about being, say, a mammal. The truth is I do not really know how I feel about being a pinball, and feel myself to be somewhat of a mystery to myself, if that’s not too ridiculous to say. I am a composite of contradictions, to be sure: slow but fast, brave but fearful, a doer who is done unto, my front my back and my back my front. But these warring essences lend little complexity to my sense of self: I am a pinball. Guide me well. Never let me drop.

Indeed, we are all composites of contradictions, mysteries unto ourselves, forever zinging between obstacles like a pinball. This is why we tell stories, to convince ourselves that the world is not without reason. But it is important that we not take those stories too seriously, or else we risk taking ourselves too seriously. Absurdity is not necessarily a bad thing. In fact, as Varallo reminds us, sometimes it is a wonderful thing, a means of keeping our thirst for meaning in check. The world isn’t going to explode, we know this, but sometimes it helps to be reminded of it.

About the Reviewer

Jeremy Griffin is the author of the short fiction collection A Last Resort for Desperate People from SFASU Press. His work has appeared in such journals as the Indiana Review, the Iowa Review, and Shenandoah. He was the 2017 Prose Fellow for the South Carolina Arts Commission, and he teaches at Coastal Carolina University where he is the fiction editor for Waccamaw: a Journal of Contemporary Literature.