Book Review

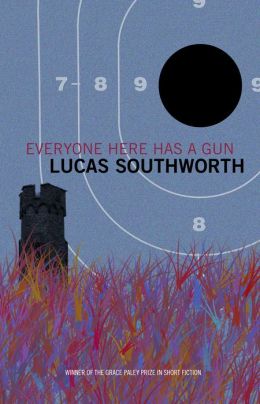

With tales of violence carried out by anonymous characters, Lucas Southworth’s short story collection delivers exactly what the title promises: Everyone Here Has a Gun. The collection of twelve stories includes characters that range from a murderous teenage paraplegic to a renowned makeup artist who is just plain fed up with her clients. Southworth throws the reader right into chaos with his opening title story. Written in second person, we are in the story with a gun in our hand along with everyone else, just waiting for someone to make the first move: “The most important thing is that eventually someone will shoot. We must always stay ready for this.” This line sums up Southworth’s gripping collection of short stories.

With tales of violence carried out by anonymous characters, Lucas Southworth’s short story collection delivers exactly what the title promises: Everyone Here Has a Gun. The collection of twelve stories includes characters that range from a murderous teenage paraplegic to a renowned makeup artist who is just plain fed up with her clients. Southworth throws the reader right into chaos with his opening title story. Written in second person, we are in the story with a gun in our hand along with everyone else, just waiting for someone to make the first move: “The most important thing is that eventually someone will shoot. We must always stay ready for this.” This line sums up Southworth’s gripping collection of short stories.

The collection is told with diverse narrative styles, such as folk tale, story in letters, model telling, to name a few. Such drastic switching between story-telling styles might seem a distraction, but Southworth does not overdo it. Instead, each story being told from a new angle allows the narrative to drive forward in a refreshing manner. For example, the second story, “The Running Legs and Other Stories,” is told in repetitive sequences. There are three threads: one of two little girls and their abusive father, one of the stepmother telling the little girls a story, and one of the girls as adults. These threads then braid together—part one, part two, part three, part one, part two, part three—until finally converging in the last section. In contrast, the next story, “Lincoln’s Face: A Resurrection,” is told in a traditional linear structure with a clear beginning, middle, and end. As boring as that may seem, it is refreshing after the complexities of the previous story. The book is laid out in a back and forth manner that won’t allow you to settle into a flow. It is this tension that Southworth is aiming for, holding a gun to the reader’s head.

But it’s the characters that really drive the collection with their extreme aggression and twisted motivations. The lack of names—the anonymity—paradoxically allows the characters to be developed and displayed in a deeper manner. In “The Safest Place You’ve Ever Been,” set in the waiting room of a clinic, the characters are reduced to simply numbers. We as readers meet these characters without the judgments and bias that often come with a name—gender, race, class. For example, “#12 wore tight jeans and a hooded sweatshirt with a designer’s name stitched across the breast.” Initial judgments must be based on the image of the character—through clothing and body language—rather than something as small as a name. The same can be said for the other character, “#13 glared at the others as if challenging them.” Throughout the rest of this story, the reader gets to know the two characters and their relationship on a much deeper level than may have been possible with the inclusion of names. Instead, we are attached to their actions and how they slowly begin to fall in love rather than their pasts.

The complexity of character is strongest, however, in “The Hundredth Confession.” This is a story of three brothers and their mentally absent and, at times, obsessed mother. The narrator, Ivan, spends nearly five pages describing the circumstances of his family and we are led to believe that he is the caretaker, the sane one looking after the family. But, to our shock, after five pages he plainly states, “this time I had come to kill [my mother].” The familial emotions that follow during the funeral and investigation are both real and surreal. This is when Southworth’s capabilities as a writer shine, as he creates a narrator that we trust as well as fear. We don’t even judge his homicidal tendencies because his motivations are fully examined and revealed. These complex emotions towards the characters are carried throughout the whole book. We both root for these people as humans, but hate them as killers.

The only shortfall of this collection is the one weak link story, which happens to fall right in the center. “All This in a World Without Dragons” didn’t hold up to the other invigorating stories surrounding it. This is a story of sons who grow up in a world without dragons and, thus, have nothing to hunt. They have pent-up energy because they have no dragons to slay and therefore, slay their fathers—or kill them in their sleep. In this particular case, one mother runs away out of fear of her son killing her husband. In only eleven not-so-short pages, this concept seems truncated—like it wasn’t completely thought out. This world seems very similar to our own, a world without dragons; yet, young boys are not killing their fathers out of sheer overexcitement. What is different about this world that makes them behave this way? A novella would have been a better fit for this concept. Luckily, the other eleven stories picked up the slack of this overeager one.

Southworth creates surprising characters and unique narrative structures that stimulate intense thought and emotion. Everyone Here Has a Gun is a short story collection crafted in a new way, with at least one story for every different kind of reader. Everyone may have a gun, but this is not a hostile read.

About the Reviewer

Malissa Stark is a Colorado writer living in Chicago. Her fiction has been published in Crack the Spine, Friction, and Story Week Reader. Her nonfiction has been published in The Chicago Tribune and The Review Lab. She is pursuing her B.A. in Creative Writing with a minor in Environmental Science at Columbia College Chicago.