Book Review

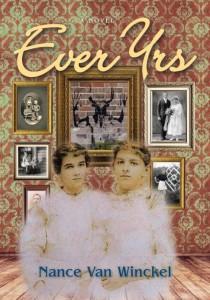

Nance Van Winckel constructs her latest novel, Ever Yrs, as a family photo album arranged by an unnamed but very elderly narrator. The novel is short at 160 pages, roughly the number of plasticky sheets you’d find in a two-volume wedding album. Inside, the novel plays lovingly between the narrator’s prose (a series of letters, notes, and remembrances addressed to an unnamed great-granddaughter), her taped-in photos, and the quirky clippings her sister Nettie kept (for reasons unknown to the narrator).

Nance Van Winckel constructs her latest novel, Ever Yrs, as a family photo album arranged by an unnamed but very elderly narrator. The novel is short at 160 pages, roughly the number of plasticky sheets you’d find in a two-volume wedding album. Inside, the novel plays lovingly between the narrator’s prose (a series of letters, notes, and remembrances addressed to an unnamed great-granddaughter), her taped-in photos, and the quirky clippings her sister Nettie kept (for reasons unknown to the narrator).

Grandy, as she calls herself, guides her great-granddaughter through the dizzying and complex family tree of her people, the Stanleys, and her husband Chester’s people, the Pettybones. Grandy is the last of her family and, because of the generosity of her grandson Buddy, lives in an assisted living home. Buddy made his fortune by inventing a game in which players move pieces around a board to escape the Minotaur in his maze. Grandy initially had her doubts that such a game would be popular, but (in Grandy’s world at least) it seems to be the Monopoly of mythology-based board games.

Grandy shares very little about the environment in which she is assembling this album, but she does explain that Jasmine, a nurse, is typing out her words and that everyone in the nursing home is hurriedly preparing for the uncertainty of Y2K. Grandy is ninety-nine years old and determined to finish this book before she’s one hundred. Aside from this—and the droll side-plot of another nurse, Polina, who claims to be a virgin impregnated by a whistle—Van Winckel’s book doesn’t follow the typical construction of a novel. It is mostly remembrance (or backstory) told in quick snippets pieced together according to the conversational flow of a woman born at the dawn of the twentieth century and nearing the end of her life at the approach of the next.

Ever Yrs is an outward expression of one character’s introspection—the background of her very self as composed from the faces of those people who came before, especially her mother and father, her siblings (who each died young and tragically), her husband (who was lobotomized in 1952 and died three years later), and even her somewhat estranged granddaughter, Sherry (who prefers “Cheri”), the mother of Grandy’s great-granddaughter. In Van Winckel’s hands, Grandy’s life can also be examined and explored as a piece of found art. The beautiful old photos of Grandy’s people—repurposed photos from people who actually lived—along with the (at times) goofy advertisements of women selling pencils or announcing contests inspired by Maidenform brassieres recalls a now (sadly) antiquated American pastime: sitting for the family portrait.

In 1839 a Frenchman named Daguerre perfected a method of chemical transference that enabled him to capture images from life. With the daguerreotype, photography steadily developed into a method for documenting life and, especially, family life. Portraits of family members, sweethearts, and deceased relatives became a way of preserving images of the people we knew and loved. A way to make the past linger in the present. Unlike the pace of photography today, imbued with over a billion selfies every minute of the day, the photographs of Grandy’s album have been carefully chosen and placed in the correct context of her memory. By assembling this book, Grandy is creating context, not only for herself, but for the great-granddaughter who is continuing the history of their family. And while a short story, a novel, or a novella cannot exist without context, Van Winckel’s novel seems to suggest that context itself is a story. Or, in Grandy’s own thinking, whatever happens in life is the only context in which it could have happened:

Sometimes I wish the stories about our family had different endings than the ones I know, or that I’d be wrong about what’s happened, and no one lost his mind, or a baby in a fire, or a brother in a blizzard. That such endings would be completely altered by some suddenly appearing new fact, and we’d find that child we thought we’d lost forever all grown up and living in the treehouse behind the old Streeter place, even though that whole neighborhood’s actually way down beneath the Berkely Pit now.

In our digital age, I think we have forgotten the novelty of the family photo album with its bound spine of self-sticking pages and assembled faces. How we used to turn its too-big pages to review our ancestors, if not to remember who they were, then at least to observe their expressions changed by laughter, caught in transition, or splashed by waves of salty and/or fresh water. True, the album (digital or otherwise) is a collection of photos, but it is also a collage of the people who came before us, or representations of ourselves at various times and places somewhere in the past—a glimpse of a prior time that we can recall because of the proof in our hands. Van Winckel’s novel is an ode to this otherwise lost expression of family. But, more than that, Ever Yrs is the family album we have always wanted to read because it is directly addressed to a person of the future from a person of the past.

About the Reviewer

Jacqueline Kharouf has an MFA in creative writing, fiction, from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her work has appeared in Necessary Fiction, Harpoon Review, Matchbook Literary Magazine, Gingerbread House, The Examined Life Journal, South Dakota Review, Fiction Vortex, Otis Nebula, and NANO Fiction, among others. She lives and works in Denver.