Book Review

These are challenging times for those committed to literary realism. Literary writers like Colson Whitehead, Justin Cronin, and Benjamin Percy have tackled zombies, vampires, and werewolves respectively and reaped the reward. Chang-rae Lee’s latest novel is a dystopian fantasy. A satirical fabulist like George Saunders is not only considered one of the masters of the American short story, but one of our most esteemed writers. Karen Walker Thompson, Karen Russell, Jamie Quatro, and Alyssa Nutting routinely transgress genre labels and conventions, grounding their work in consistency of style and voice.

These are challenging times for those committed to literary realism. Literary writers like Colson Whitehead, Justin Cronin, and Benjamin Percy have tackled zombies, vampires, and werewolves respectively and reaped the reward. Chang-rae Lee’s latest novel is a dystopian fantasy. A satirical fabulist like George Saunders is not only considered one of the masters of the American short story, but one of our most esteemed writers. Karen Walker Thompson, Karen Russell, Jamie Quatro, and Alyssa Nutting routinely transgress genre labels and conventions, grounding their work in consistency of style and voice.

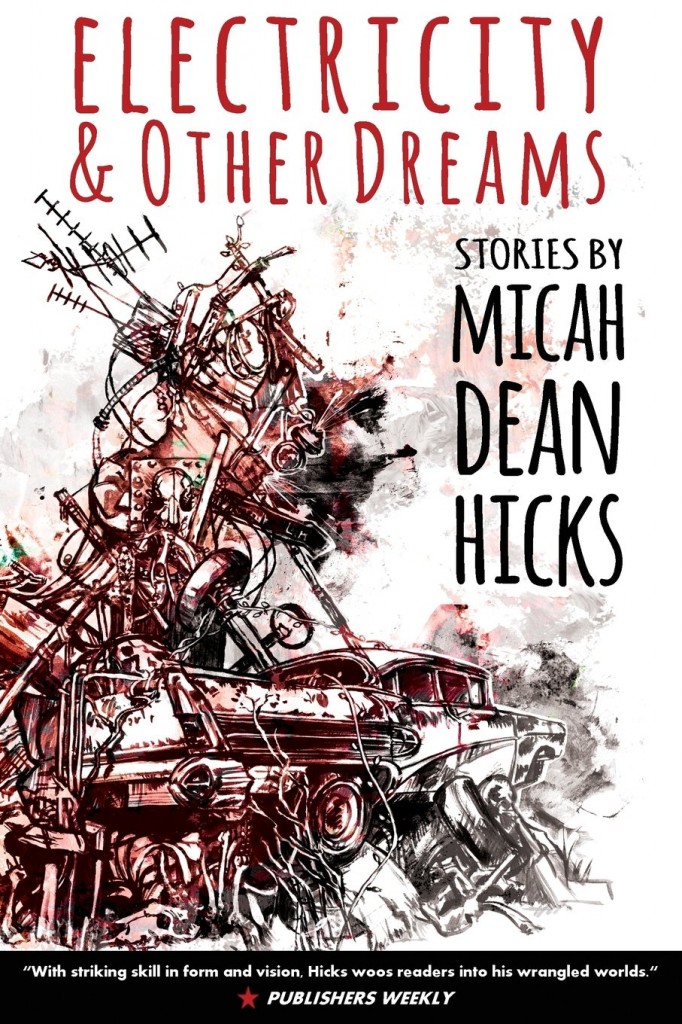

Salmon Rushdie once defined magical realism as the “commingling of the improbable and the mundane.” By those lights, all the writers mentioned above might be called magical realists, but no one comes closer to the embodying the full range of possibilities inherent in the genre than Micah Dean Hicks. In his short story collection, Electricity & Other Dreams, Hicks takes the familiar iconography of American culture and, with formal precision, upends it by means of fabulist elements that often underline the grimmest of portents. Sometimes he resorts to the familiar tropes of fairy tales—witches, giants, enchanted shrubbery—or the stuff of legend, like the story of Bluebeard. Hicks mines older stories for meaning while revealing unsettling layers of implication. What is most unsettling about Hicks’s stories is how they resonate with the possible. His bizarrely precise visions forge an eerie alliance with American daily life. Hicks, with his seemingly limitless talent for invention, is a master of North American magical realism.

Latin American magical realism flourished during the reign of the dictator-generals, when people were routinely “disappeared” by government thugs, imprisoned and tortured without even the pretext of due process. The magical realist tradition, with its roots in indigenous magic and folk tales, was both an act of collective resistance and an affirmation of national identity.

In this country, the present cultural moment seems particularly rife with monsters, witches, and mythologized superheroes while the public stands by helplessly as the American government, with its penchant for universal surveillance, unlimited incarceration without benefit of trial, and lopsided foreign interventions, is regularly shut down by a contingent of right-wing elected anarchists. Reality has taken flight from our collective life. During times like these, a fabulist imagination like Micah Dean Hicks’s acts as a tonic.

It is fitting that the collection’s lead story, “The Time of the Wolf,” is set in some nameless Middle Eastern land. The American imagination is on endless deployment in these desert lands. In the story, a character known as Contractor Jackson enters Abdul Karim’s bazaar in Contractor Town to buy a present for his son. And, like all Americans wandering in the desert, civilian or military, Contractor Jackson encounters a culture whose ancient magic will never bend to his will.

Hicks is equally at ease restoring magical implications to modern technology. In the story “Where the Electrician Went,” Hicks uses an established technology—electric lights—to demonstrate an essential truth about the trailblazers dragging us forward into the future. The mad electrician brings light, but most of the people he brings it to would prefer to shelter in darkness. Here, Hicks demonstrates a genius for revealing the simple truth of what many people already think and feel about the light-bringers and trailblazers who change our world by further dividing us from the familiar comfort of the natural.

A trio of good ol’ boys is out hunting gator in “The Alligator’s Gods,” draining their beer cans and crushing them on the floor of the truck, “where the shifting mass clattered and rolled under their feet with every bump, the old beer smell mixing in the air with wide bands of cigarette smoke. This truck was more their place than anywhere else in the world.” We may not have been to this place, but we know it. And when the back of that truck begins to fill up with gators, piled on top of each other like so many logs from an old growth forest, we feel an almost routine despair. The story that emerges from these grimly familiar circumstances will upend the reader’s expectations in a way that seems refreshing while falling well short of hopefulness.

“Crawfish Noon” demonstrates Hicks’s penchant for mordant wit as he maps the most American of archetypes—the Western gunslinger—onto a population of East Texas crawfish, in particular a gambler named Seven-leg who’s been betrayed by a member of his gang and aims to gun him down. No one will ever accuse Hicks of not making this one work, especially during the showdown when “no one moved until a larva ran out in front of Tom Boiled—a scrawny thing, not much past a nauplius—and Tom skewered it with one sharp foreleg, shoved it in his mouth and ate that little bastard with his parents watching from their door. Shit got bad then.” This story clarifies Hicks’s method—by taking the time-honored locales of American myth and allowing them to be taken over by the least likely inhabitants, he startles us into a new appreciation for their potential, both comic and tragic.

Hicks’s stories create meaning the way the unconscious does—revealing elemental structures via metaphoric substitution. At first you may be tempted to keep reading just to see what Hicks is going to do next, how he will redistribute the pattern by substituting unlikely elements for its most fundamental parts. And that’s when he will do something really disturbing. “The Lost Loves of Danny Lowe” begins with a heartbreakingly resonant sentence: “All the lost loves of Danny Lowe, his lifetime of lonely nights, began that evening at the barn party.” In this story, Hicks demonstrates that he’s more than just a gifted imaginer, he’s a gifted and daring stylist, using rhythm and alliteration to lull us into a world where lust, violence, and the metal-smell of omnipresent machines combine to create a story firmly rooted in the realm of horror, one that echoes the manic tension found in Edgar Allen Poe.

In “The Butcher’s Wind Chimes,” Hicks creates horror in a story that mimes the form of a Grimm Brothers folk tale. An old woman who lives deep in the woods cares for her nine unruly grandchildren. The old woman teaches the children to make wind chimes, which she loves, and when the meat fair comes to town, she teaches them to steal. Many of Hicks’s stories take the form of devil’s bargains. As in the old tales Hicks re-imagines, the characters in his stories often learn too late that they have gambled with fate and lost.

In some of the stories in this collection, Hicks displays an easy mastery of literary realism, but his stories are never completely realist. “Ash Flowers” is about the kind of quiet girl who trudges home from school with her shoulders curved under the weight of her book bag, only to discover a house full of flowers when she arrives. Her mother has stolen them from local funerals because no one ever brings her flowers, and she’s sure she deserves some. But the girl and her mother and sister are only waiting for their father to come home, when the blooms stolen by this selfish woman will reveal what she really deserves.

The magical elements in Hicks’s stories are set against the backdrop of the ordinary, not to make quotidian characters and details seem strange to us, but to make us realize how strange they already are. A man’s generosity threatens the inhabitants of an apartment complex, the kind where everyone’s windows overlook the parking lot; a plumber drinks ghosts; gun-wielding jugglers ply their trade at a local waffle house; a weatherman finally learns to make the weather do his bidding, only to lose the weather girl who was his sole reason for undertaking the quest. When Hicks dabbles in the mythologies of other cultures, he’s not doing it to explore difference, but to explore the American pop culture version of a particular brand of foreignness. “The Warlord Reishi” is as American as the local tae kwon do academy. “The Hairdresser, the Giant, and the King of Roses” isn’t simply an updated fairy tale, it’s the Americanization—the conquest—of an entire genre.

And yet, despite Hicks’s imaginative conquest of the jinni, witches, and giants of millennia of anonymous legend, he means them no disrespect. He doesn’t toy with their power; he uses it to draw us up short, to make us pause. There’s something more than a little addictive about Micah Dean Hicks’s fractured fairy tales, but you won’t find yourself plunging from one of these stories to the next. Instead, you will read them one at a time, pausing in between to let their resonance, if not their meaning, unfold.

Published 3/31/14

About the Reviewer

RT Both is a doctoral student in fiction writing at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. Her fiction, creative non-fiction, and articles have been published in magazines, journals, and newspapers that include The Brooklyn Review, Cream City Review, Weep, Chicago Magazine, and the Sunday Milwaukee Journal.