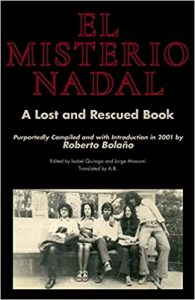

Book Review

The poet behind El Misterio Nadal performs the mercurial poetic achievement par excellence of disappearing into the work itself. Although somewhat described as a novel this is no more a novel than is poet Jack Spicer’s Rimbaud. No, this is no novel. This is writing about writing itself that explores the intersections between the life, or lives, of the writer(s) and the written work(s). A ribald blast of immersion into the meta-poetic, if you will, which is only further compounded by the mystery of who is really behind this work. As “translator” A.B. explains:

The poet behind El Misterio Nadal performs the mercurial poetic achievement par excellence of disappearing into the work itself. Although somewhat described as a novel this is no more a novel than is poet Jack Spicer’s Rimbaud. No, this is no novel. This is writing about writing itself that explores the intersections between the life, or lives, of the writer(s) and the written work(s). A ribald blast of immersion into the meta-poetic, if you will, which is only further compounded by the mystery of who is really behind this work. As “translator” A.B. explains:

The annotations to this text (with the exception of the notes to the republished

materials relating to the great Surrealist poet Benjamin Péret) have been made by “Robert Bolaño,” “Isabel Quiroga,” and me. One set of notes (to the Octanovitch Pazinsky speech, at the end of the book) is possibly made by Jorge Mosconi. I place the names of Bolaño and Quiroga in quotes in this first instance, for the nature and extent of their involvement with this manuscript, handed down to me by Mosconi, is still open to question (see my Translator’s Presentation, preceding).

Apparently a pile of manuscripts and assorted documents have been sifted through—including ones lost, as well as others newly recovered—to assemble this wonky, at times rather unwieldy, volume. It might be said that the work is itself in search of the work itself. A cagey, pseudo-literary detective tale of lost ends and sham beginnings, this collaged together document draws upon numerous texts by multiple authors and various translators for a wild immersive dip into Mexico City’s infamous Infrarrealistas group and beyond. As “editor” Isabel Quiroga tells it:

I want to believe that what you have in your hands is a lost work of Robert Bolaño —one that, if not written wholesale by the great author, is at least authentically introduced and partly annotated by him. Readers familiar with The Savage Detectives will not be able to miss that key structural devices—most notably the extended epistolary section that follows his introduction—are reminiscent of that book, published three years before Bolaño claims to have “found” this manuscript “by” a furtive figure called “Nadal.”

The resulting document is a textual/taxonomical exposé exploring the group’s ties to the European avant-garde, particularly Surrealism, “purportedly compiled” by the group’s ultimate “star” Robert Bolaño yet predominately written and/or translated by the mysterious figure Vladimir Nadal, around whom the work centers. The original manuscript was initially edited by Isabel Quiroga who received it in the mail nine months after Bolaño’s death. Shortly before her own death, Quiroga passed it on to her acquaintance Jorge Mosconi—who in turn sent the work on to the reputed translator, one A.B. (“Arturo Belano”). Whatever may be said about any of these figures, it must be that one (or perhaps none?) of them is The Poet responsible for this intriguing book.

Many writers are identified as contributing to the text itself. In addition to A.B.’s voluminous notes and his opening “Translator’s Presentation,” there is Quiroga’s “Translator’s Preface” as well as a lengthy “Introduction” by Bolaño himself. And there is “Searching for Nadal” a section composed of selected letters to Bolaño written by various writers—all mutual friends—discussing the enigmatic Nadal. Adding to the peculiarity of just who wrote what are remarks regarding this section made by Quiroga in a footnote:

It is interesting that the surnames for the correspondents in the “Some Memories of Nadal” section are also used as pseudonyms in The Savage Detectives. However, it is clear that the pseudonymous surnames applied in the letters herein do not denote the same historical persons to whom the surnames are applied in The Savage Detectives. Is this nominal recycling and scrambling just a convenience, or is it some kind of joke by Roberto?

Nevertheless, it is precisely this interconnected chorus of voices all recalling the elusive figure each knew from out their youth together—but only few had intermittent contact with in later years—that somewhat enlarges the void of information surrounding Nadal—as much as it fills in incidentals regarding his personal characteristics, struggles, fleeting friendships and occasional romances.

Then there are brief remarks again by Bolaño on French Surrealist Benjamin Péret followed by a text introducing Péret written by North American Surrealist of Chicago Franklin Rosemont lifted directly from out Radical America v.4, no.6 (Aug, 1970). Next comes a dossier of material on Péret: two lengthy, incomplete transcriptions of Brazilian police interrogations of Péret (who was ejected from Brazil 1931 shortly after these interrogations are claimed to have occurred) copied from police files by Nadal and translated by him or someone else into Spanish; Péret’s essay “Black and White in Brazil” as it appeared in Nancy Cunard’s The Negro Anthology (1934) translated by Samuel Beckett; Péret’s “The Dishonor of Poets” translated by Cheryl Seaman also from the same issue of Radical America; and ten poems by Péret that have been translated by Nadal with varying degrees of faithfulness to the original texts.

The Péret material, particularly the interrogation transcripts, presents a fascinating glimpse into the cross-cultural conflicts between art and politics as the enthusiastic spirit of Communism became usurped by the emerging threats of Stalinist terror and the fascist advance of the Nazis hungering after global power.

Q: You will show respect, Sr. Péret. You are playing with fire.

BP: But otherwise, back to your fascination with Surrealism; your biggest mistake is to so simplistically confuse the artistic statements of Surrealism with its revolutionary positions, my dear interrogators. True, they often overlap, and in deep manner. But they are not the same. For example, in France, Surrealism fights within the Communist Party for a complete autonomy of poetics and art; the Party bureaucrats of Moscow and Paris want to chain artistic expression to Party command. We reject that, absolutely and mercilessly. We are for the freedom of Art.

How Nadal ever got his hands upon the transcripts is a pure act of 007-inspired poetic handiwork.

Finally, in closing, there is the chaotic, rather rambling, a bit drunken diatribe of a speech delivered by the figure “Octanovich Pazinsky” (aka Octavio Paz) “at the Official Socialist Infrarealist Writers’ Congress, founding the Union of the New Infrarealist Writers of the United Specialist Poetic Republics (USPR)” in April, 1934, during the First Congress of Soviet Writers in Moscow (during which Pazinsky upsets basic laws of physics and much else managing to discuss poets who only published work decades later—at times he as well seems to be echoing Charles Olson’s infamous Berkeley lecture of 1965). It provides for bizarre reading.

And it is no accidental that here, at the congress, both in Comrade Huertapov’s report and in the speeches delivered by many writers, so much should have been audibled about the people’s art. Yes, in our country the people is once again producing its singers, its artists, its Infrarealist heroes, in this time when the whole countryside is being electrified into Infrarealism by our vanguard Search Engines! [Applause]. Every year sees the rising up of fresh rootings of new Infrarealist writers, who come from the pit of the workers and collective serfs and who sometimes become immortal to the whole country with their very first plagiarism and theft. [Applause and shouts of “Death to bourgeois morality!”]

In what ultimately becomes a mystery of poetic investigation turned inside out, The Poet dives into the subject matter, yet avoids commenting upon or dissecting the work at hand instead immersing the text in the creative usurpation of the connections between all these individual figures and their actual lives, indelibly mixing and imbibing (in another nod to Spicer) The Real of The Poem with Reality itself. If nothing less this book represents the Poetic Mind writ large, engagingly divergent in its various offerings of assorted lenses through which the creative life is rendered. Whoever The Poet responsible for this book might be, he or she is a sumptuous obsessive over Poetry—ever well informed as to the nature of this most acroamatic activity.

About the Reviewer

Patrick James Dunagan lives in San Francisco and works at Gleeson Library for the University of San Francisco. He is author of The Duncan Era: One Poet’s Cosmology (Spuyten Duyvil). He recently assembled a portfolio honoring poet David Meltzer for Dispatches From The Poetry Wars. With Nicholas James Whittington and Marina Lazzara, he is editing an anthology of writings by alumni and faculty of the now-defunct Poetics Program at New College of California.