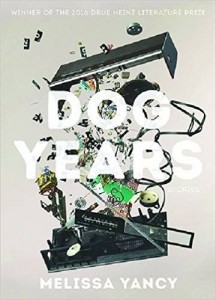

Book Review

Melissa Yancy’s debut collection, Dog Years, is excellent. Normally I would give examples of Yancy’s finely tuned writing, maybe a passage of description or subtle dialogue, but the collection is so consistently excellent that it’s hard to choose. It’s also hard to choose just a few stories to highlight. They are all realistic literary stories, but what strikes me now, looking back on the whole experience of reading Dog Years, is the diversity of shapes the stories take. To emphasize these striking and diverse shapes, I’ll turn to the late Jerome Stern, who in Making Shapely Fiction described the various shapes that can embody a writer’s imaginings.

“Go Forth” is what Stern would have called a “Journey” story. In it, an elderly married couple who are part of a kidney chain take a trip to meet their respective donor and donee. The wife, who received a kidney, is excited to join this new community. The husband, who donated a kidney so his wife could get hers, is more cautious. Their reactions to the experience are unexpected—an interesting reversal of roles—but what most strikes me about the story is Yancy’s ability to enter the minds of her elderly protagonists. By doing so, Yancy make us understand the nuances of their partnership, which, unlike others in the collection (and in life), will almost surely withstand whatever comes its way.

“Firstborn” is what Stern would have called a “Visitation” story, wherein an eccentric loner, a self-described mistress and aunt (as opposed to wife and mother), is reunited with her niece on the eve of their trip to Europe. Though the story is rich in background, it’s dominated by a single scene between these two characters. Yancy stretches out the scene with delicious and sometimes hilarious awkwardness as the protagonist’s memories are contradicted by those of her niece. The two are an odd pair. The niece wears a tracksuit with “Juicy” lettering, whereas the aunt longs for her old Kenzo-print silk shirts. When pressed, the niece says she’s looking forward to seeing the Eiffel Tower, whereas the aunt has fantasized about a “walk through the streets of the 18th arrondissement flanked on each side by a royal silver-blue feline.” The visit doesn’t end well.

“Miracle Girl Grows Up” is a sort of “Last Lap” story. While Stern’s example of the “Last Lap” shape is of a story that opens on a character partway up the face of a cliff, the cliff in “Miracle Girl Grows Up” is a series of mediocre dates and, we intuit, the possibility of trusting other people. The “Miracle Girl” of the title is miraculous because she had a teratoma (a rare and bizarre type of tumor containing limbs, organs, hair, or teeth) sliced away from her at birth. The connection between the teratoma and the woman’s current struggle is never made explicit, but the teratoma haunts the character and her story. Though she isn’t a showy writer, Yancy marshals some of her most vivid (and disturbing) descriptive writing for the teratoma: “Her face had been melting off into a second face that lay alongside her like an enormous puddle of flesh.” The story ends up centering on whether the woman will choose to strike up a romance with a congenial voice actor. In the climactic scene, he surprises her by showing up at her workplace, a children’s hospital.

One of the finest stories in the collection is “Consider This Case,” which has something in common with the “Last Lap” shape of “Miracle Girl Grows Up” in that the protagonist, a fetal surgeon, must decide whether to enter a romantic relationship. But the heart of the story is the surgeon’s relationship with his ill father who, at the beginning of the story, moves in with his son. The father, a former White House interior decorator, approves of neither his son’s austere (and outsourced) home décor, nor much about his son’s life. Interestingly, both men are gay. The father, who doesn’t admit that he’s gay (only “deeply southern,” according to his son), seems more comfortable in his own skin than his son does. The son’s tidy, controlled life as a bachelor surgeon is threatened by his father, and Yancy uses the encounter to show two ends of the healthcare spectrum. The son is a specialist, and his relationship to his patients is clinical and somewhat impersonal, whereas his father’s condition requires something more akin to palliative care, which the son is ill-equipped to provide.

“Consider This Case” is great, and so are “Dog Years” and “The Program,” which I haven’t even mentioned, but my favorite story in the collection (this is the kind of collection that compels me to tell you my favorite story) is “Stray.” “Stray” represents both a “Visitation” and a sort of “Last Lap,” and Yancy, who seems to be a writer of supreme confidence, really takes her time with it. “Stray” is about a woman who takes in an abandoned child, but ten pages pass before the little girl shows up. The first ten pages are about animals, and the narrative escalates like an elaborate joke: swans, dogs and cats, fifty shrimp kept in a bathtub until their predictable demise. We wonder whether the protagonist, who has an unusual personality that seems to prevent her from forging relationships with other people, will choose to keep the child, and if the child’s parents will return for her. I won’t spoil it.

Healthcare figures prominently in many of the stories: there’s a children’s hospital, a kidney chain, a fetal surgeon, and a boy with Duchenne muscular dystrophy, among others from the world of illness and treatment. Yancy works as a fundraiser for healthcare causes, and has worked at a children’s hospital, so it’s tempting to attribute the sensitivity and authority with which she writes about that world to her personal experience. But to do so would undersell Yancy’s skill as a writer. Yancy seems to be an artist who sees everything clearly, and who can make us see, and feel, alongside her. I look forward to reading more of her work.

About the Reviewer

Bradley Bazzle is the author of the novel Trash Mountain, forthcoming from Red Hen Press. His short stories appear in New England Review, New Ohio Review, Epoch, Web Conjunctions, and elsewhere, and have won awards from Third Coast and the Iowa Review. Some of them can be found at bradleybazzle.com. He lives in Athens, Georgia, with his wife and daughter.