Book Review

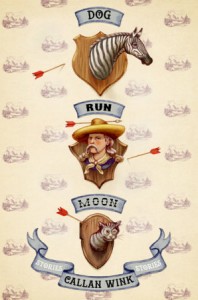

Sid is a nude sleeper running from a man known as Montana Bob. James is a teacher who takes a summer job at a hunting ranch populated with exotic animals. August kills cats; his parents aren’t speaking. Dale’s girlfriend has a crazy husband, and Perry has been playing General Custer in the annual Big Horn County Civil War reenactment for years (while having an affair with the Native American woman who pretends to kill him on the battlefield year after year after year). These are just a few of the vivid and memorable characters in Callan Wink’s first story collection, Dog Run Moon, which introduces readers to the dangers and idiosyncrasies of life in the American West.

Sid is a nude sleeper running from a man known as Montana Bob. James is a teacher who takes a summer job at a hunting ranch populated with exotic animals. August kills cats; his parents aren’t speaking. Dale’s girlfriend has a crazy husband, and Perry has been playing General Custer in the annual Big Horn County Civil War reenactment for years (while having an affair with the Native American woman who pretends to kill him on the battlefield year after year after year). These are just a few of the vivid and memorable characters in Callan Wink’s first story collection, Dog Run Moon, which introduces readers to the dangers and idiosyncrasies of life in the American West.

Wink’s collection gets off to a running start with “Dog Run Moon,” the title story, which appeared in the New Yorker and introduced Wink’s writing to the literary public. It begins in medias res as Sid (the aforementioned nude sleeper) streaks through the harsh, blackened landscape beyond his trailer in a half-witted attempt to escape Montana Bob, whose dog he’s stolen. Excuse me: whose French Brittany spaniel he’s stolen. Montana Bob is very particular about that fact. Sid, who isn’t interested in the dog’s pedigree, liberated it from Montana Bob’s yard because no one appeared to have any love for it but Sid. Sid is jealous of the dog’s sleek coat, its thick foot pads, its beautiful bird dog’s nose, with its accompanied ability to sniff out game. Following Sid in his run, one gets the sense that he would like to be a dog, and that this flight is in some ways an attempt to become a kind of animal, free of the responsibilities of being a man. When he thinks of running to his ex-girlfriend’s house and begging her to wash his feet, it’s clear that he wants her to take care of him, like he took care of the dog. He doesn’t have anyone to love him.

Moments of tenderness are rare in this collection, which sees lives ruined and cattle murdered all in the name of retribution, but when some tenderness does bleed through, it’s usually in relation to animals (Sid’s dog, for instance, touches its nose adorably to the windshield of Sid’s truck). In the collection’s fourth story, “Breatharians,” the unsettlingly intimate violence of August’s mission to smash the heads of all the cats in the barn is tempered by the knowledge that he had a “birth dog” and that it died recently. This term—birth dog—was enough to make me put down the book for a moment. Its sweetness and accuracy left me wondering how I’d never heard that term before, and if, when my parents brought home my dog, Duke, a purebred cocker spaniel, their intention was for him to be my “birth dog.” That Wink’s writing made me reevaluate a relationship that I’d long considered understood is a testament to his skill and vision as a writer.

Of the nine stories included in this collection, perhaps the best is also the longest: “In Hindsight,” the first and, it seems, the only New Yorker novella. (This series was meant to showcase works of longform fiction that the magazine wasn’t able to publish due to length constraints, but it appears, as of this writing, to have been placed on an indefinite hiatus.) Wink’s novella thus stands alone as a singularly brilliant work of fiction that showcases all his strengths as a writer: his spare, precise prose; his deft use of landscape; his mastery of voice; and his ability to make an animal’s death at once the most commonplace and catastrophic event in a person’s day. “In Hindsight” opens on its main character, Lauren, pulling up the drive to find that one of her steers has been slaughtered by her son-in-law, who resents her for getting the house after her husband’s—his father’s—death. As the novella progresses, the standoff between these two characters forces Lauren to reexamine her life. In hindsight, she has a lot of regrets—like allowing most of her life to be spent in the care of others or not leaving with the woman who loved her when she had a chance—but in the moment, sitting there and petting her dogs, life seems more or less manageable.

Considering “In Hindsight” beside Wink’s other stories, a unifying thread reveals itself in that his characters are all, in some way, engaging in standoffs and mock standoffs: Perry in his Civil War reenactment, August with his cats, and Lauren with her son-in-law. Even Lauren’s dog (playfully dubbed Elton John) does it: he’s “steering clear of the cattle, engaging in mock standoffs with the cats.” This is a world where everyone and everything must lay claim to what’s theirs, then defend it with all their strength, whether it be dogs, steers, lovers, families, or even memories. There’s an important moment in “In Hindsight” when Lauren attempts to explain to her son-in-law why she married his father and says, “I married him because I’d loved someone and made a mess of it and I wanted something to take my mind off it. To punish myself for being stupid. Maybe I needed to be needed. I don’t know. It was a long time ago and things get muddled. I never wanted his shitty land.” Finally, after decades of fighting over the land, it becomes clear that what Lauren has been fighting for is really her right to exist without a standoff. To answer to no one and be beholden to nothing. In a collection where standoffs often turn deadly, not being caught up in one seems a lot like happiness. Finding that happiness in Wink’s work was a pleasure, and I’m looking forward to what he writes next.

About the Reviewer

Ruth Joffre is a writer and a critic whose work has appeared or is forthcoming in Kenyon Review, Hayden's Ferry Review, Mid-American Review, Copper Nickel, Diagram, the Millions, and Full Stop, among others. She's a graduate of the Iowa Writers' Workshop and lives in Seattle, where she teaches at the Hugo House.