Book Review

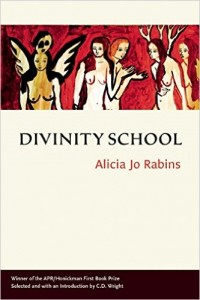

Alicia Jo Rabins’s poetry brings to mind the variety and vitality of water. The word estuary comes from the Latin aestus, meaning heat, boiling, bubbling, or tide. Such diversity of meaning parallels the union of opposing elements that Rabins enacts in her poems. As fluent in the music world as in the world of poetics, Rabins created a one-woman chamber-rock opera (A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff) in which mysticism and finance—an unexpected combination—intersect. Rabins’s Divinity School is also about how disparate ideas and imagery coalesce, and how such unions reveal the value of their components.

Alicia Jo Rabins’s poetry brings to mind the variety and vitality of water. The word estuary comes from the Latin aestus, meaning heat, boiling, bubbling, or tide. Such diversity of meaning parallels the union of opposing elements that Rabins enacts in her poems. As fluent in the music world as in the world of poetics, Rabins created a one-woman chamber-rock opera (A Kaddish for Bernie Madoff) in which mysticism and finance—an unexpected combination—intersect. Rabins’s Divinity School is also about how disparate ideas and imagery coalesce, and how such unions reveal the value of their components.

Divinity School seems to be full of estuaries, places where foreign ideologies are able to coexist. Rabins assures us there isn’t shame in secularizing the sacerdotal, showing the reader that “our training involved LSD and cathedral nights.” She writes: “We dreamed of immortality / We flexed our young flanks / We practiced beauty on each other.” There cannot be breadth between the sensual and sacred if we are to uncover ourselves, the poet insists. Divinity School often serves as an instruction manual to recognize the mysticism of passing moments. Sailing involves removing curses and traveling time; cross-country skiing is witnessing “a moon silence,” where the skier is urged to “read the snow while it scrolls across the hills . . . it’s in the static.” Outdoor recreation is access into spiritual Nature. Can the laws of rationality exist without transgressing into the fantastical? Can we pray without the body? In Divinity School, the coalescence of the disparate leads to questions. Telling time must be conveyed through parable. “A Vaccination for Loneliness” unifies physical, emotional, and spiritual pain: “O Lord, the praise on my tongue / has turned to fear.”

Besides the boundaries dissolved between physical and metaphysical realms, the curtain that separates those who are holy from those who are not is torn. Rabins implies that any person may become a prophet: “there is a frozen waterfall / at a man’s center,” she writes. To be receptive to “God’s word” is to be the man’s lover, making the water flow. In “The Magic,” a makeup artist bestows the secrets of beauty upon fellow mystics. The poet imbues ordinary, human tasks with the power of ritual. The poet displaces the distant concept of God with the human “Earth Room Man”—a security guard who overlooks and tends “the soft brown soil” of the Earth Room. Despite being “a man at a desk like any other,” the poet attributes power to his position as watcher. She declares, “I think you’ve grown wise from that.” The narrator prays to the Earth Room Man of time passed, the instance she “wasn’t afraid of death for the first time.” Conversely, the holy figure of Noah is stripped, through language, of sanctimonious certainty. Divinity School could be seen as a creative form of Midrash—the Judaic practice of applying linguistic interpretation to religious texts. In “The Story of Noah,” the poet addresses the ancient word tsohar, the meaning of which has been lost through time. “In the wooden wall of the ark was a tsohar. / This was a. a window b. a glowing precious stone c. we don’t know . . . in the wooden wall of Noah there was also a tsohar. Sometimes the voice of God would come through.” The obliqueness of language becomes Noah’s own uncertainty in translating heavenly orders.

Not only does Rabins capture tides, but her poems draw attention to what memory has taken. She expresses this elusiveness in the book’s title poem: “I kept thinking about suffering / and how until I look at it there is no movement.” Vision grants the seer some power over time’s losses. A single circumstance may produce multiple sides, or the fragmenting effect of perspective may be dissolved. In Rabins’s murder ballad, “A River So Wide,” the roles of God and Satan are interchangeable. One cannot exist without the other, and one cannot know for certain to which their temple is built. In “Too Late,” Rabins analyzes the necessity of the divisions in life:

. . . just as God

cannot unmultiply, defruit, divide,

undo dominion, close rib-flesh over, thumb

continents together, unsplit upper & lower,

watercolor all firmament, all hovering.

Here Rabins alludes to the inevitability of darkness, and how it may provide the individual attainable meaning.

Though Rabins will never directly tell you why, she will almost always show you how. “In the jade room I am jade. / In the infrared room I am silent. / In the cold plunge I am mute,” Rabins writes. Not only has the poet’s selfhood been threatened by dissolution into her environment, but the reader’s identity has been altered by communion with the poet. The senses of both are wracked by synesthesia. The reader then meets the narrator at a sushi bar where both are surrounded by a “panorama window.” Perhaps this is the oppressive yet grounding force of language. Following this, the poet affronts and accepts her reader in the same gesture: “we animals, / having been ice, having been jade, are changed.” The reader has been accosted on this metaphysical voyage, made to transform. Yet Rabins doesn’t leave the reader in such a compromised state:

When the ripening course

is complete, the separation

course begins. An ice land

must be entered alone.

Freedom of will is returned to the reader—opened to alteration, she may walk where she wants now. Rabins reveals that our gestures allow us to know our bodies, and the emotional associations of our words and choices are what define us: “I see death, I see profit . . . a piece of jade / in the hand, a piece of gold / to carry in the dark.” Our talismans reveal our experiences, which in turn reveal our values. What we call the stone will foreshadow what we choose—how we hold the stone may determine our lives.

Rabins considers the meeting place between death and birth. This device for intersection is revealed in “The Chute”:

Each time a baby is born

the universe squeezes itself

through a chute,

the same chute

into which

suicides squeeze themselves.

If arrival and departure occur at the same location, how must we imagine the architecture of the interval between? The poems in Divinity School prod tenderly at our faltering perception of time and place. They imagine how we can exist in each instant, as limitless and densely fragile: “We are the ocean and our speaking is the waves, each phrase / a little breaker spreading its foam, then a pause, and then another.” We carry on through our speech, which is eternal; art facilitates this. The space behind an object in motion is known as a slipstream: an opening in which a wake of water or air may follow at the same velocity as the original object. This, in Divinity School, is the relationship of word to experience.

About the Reviewer

A writer, artist, and actor, Grayson currently studies at the University of the Arts. They have published a book of fiction through Parnassian Publishing, the publishing company they founded, and have worked as an artistic consultant on a variety of projects.