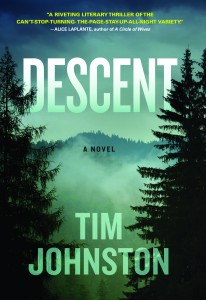

Book Review

Descent by Tim Johnston is less a story of a kidnapped teenager’s escape from the mountain home of a psychopath and more a story of the girl’s family’s descent into self-destruction while they ascend the mountain to find her. Caitlin Courtland, in preparing to become a college track star, has come to the Rocky Mountains of Colorado to train in the rigorous thin air one can only experience at altitude. While her parents are still back in the hotel room, Caitlin and her brother Sean go out for an early morning trail run. It’s not far into the book that a truck hits Sean high in those mountains, and he is left for dead while the maniac behind the wheel takes Caitlin. This is a story of finding Caitlin. Johnston tells the story in a winding fashion mimicking the hairpin curves of a mountain road, delving deeply into each character, no matter how small a role they play, making the mountain a character in itself. Readers may come for the thrill and mystery, but they stay for the incredible transformations of the characters in their time of tragedy.

Descent by Tim Johnston is less a story of a kidnapped teenager’s escape from the mountain home of a psychopath and more a story of the girl’s family’s descent into self-destruction while they ascend the mountain to find her. Caitlin Courtland, in preparing to become a college track star, has come to the Rocky Mountains of Colorado to train in the rigorous thin air one can only experience at altitude. While her parents are still back in the hotel room, Caitlin and her brother Sean go out for an early morning trail run. It’s not far into the book that a truck hits Sean high in those mountains, and he is left for dead while the maniac behind the wheel takes Caitlin. This is a story of finding Caitlin. Johnston tells the story in a winding fashion mimicking the hairpin curves of a mountain road, delving deeply into each character, no matter how small a role they play, making the mountain a character in itself. Readers may come for the thrill and mystery, but they stay for the incredible transformations of the characters in their time of tragedy.

Four storylines, one for each family member, braid together to create this novel, each showing a different approach to dealing with trauma and reflecting how the family members fall away from one another. The first and most exciting storyline is Sean’s. After being forced to go back to Wisconsin with his mother while his Dad stays in Colorado to search for Caitlin, the teenage boy steals his father’s pickup truck and begins to drive across the country. As he drives, the things his body feels tell the reader his story: a gimp leg from getting hit by the car, a cigarette in hand to show how he’s matured, a body that is leaner to show how losing his sister has affected old habits (no longer is he the fat kid). “Grant studied his son’s face—grown thin in the last year, like the rest of him. The soft blond mustache he ought to just shave.” He drives to Colorado to help in the search and must work odd jobs along the way in order to get there. All the while he is working out his own guilt that he could have done more.

Meanwhile, dear old Dad, Grant, has made a new life for himself. He has moved in with the local sheriff’s dad and spends his time fixing things up around the ranch for him as well as flirting and essentially dating the waitress at the diner. While rescuing Sean from jail he finds himself thinking of his new life, “He seemed very far away from the mountains and the ranch and the people he had come to know: Emmet and his sons, Maria and her daughter.” His tactic to seemingly avoid the issue of his lost daughter hits hard with the reader against his son’s strong-willed, do-anything approach.

But in juxtaposition to both of these, Angela, Caitlin’s mother, has flown far over the edge. She is living with her sister back in Wisconsin, no longer working, spending stints in the mental hospital and talking to her dead sister. She occasionally sleeps in her daughter’s bedroom and strokes her old hairbrush, “After a long moment Angela reached and touched. Fine lacings of hair deep in the bristles. Hairs still eighteen and silky. Hairs that would never age.” It’s moments like these that show that this is a woman who most likely will never move on.

While Grant buries his head in the sand, Sean does whatever he can, and Angela flies over the cuckoo’s nest, Caitlin remains rational. She counts the time she’s been gone by the dates on the magazines her captor brings, gives herself advice from the voice of an older and wiser self: “There is only you. There is only you.” For a kidnapping story, Johnston gives very little of the juicy details of the missing one’s life. For a while Caitlin appears in every other chapter, but then fades away until she is found. No matter how interesting it is to watch the other lives fall apart, nothing is as compelling as Caitlin’s story, Caitlin’s voice. Johnston could have given his readers more.

Johnston has a gift for creating human, flawed, dynamic characters. Picture a really good sheriff, the kind who is the hero for his small town. Now picture that guy’s misguided brother, a classic, screwed-up, alcoholic good-for-nothing. That’s Billy, the twisted brother of the sheriff. Johnston paints a person to hate. In one instance Billy is dragging his elderly father, Emmet, inside with violent force, “Emmet dug at his son’s fingers and planted his feet but with a modest tug Billy yanked him off balance and got him clomping pitifully toward the screen door.” Beyond that Billy is racist and maybe a bit of an animal abuser. Then Johnston turns it all on its head and Billy is suddenly the hero. With all of his characters he goes for unexpected choices. Instead of the stereotype: sometimes good people make bad choices, we are presented with the twist that sometimes bad people make good choices. Other characters, like Reed Lester, Carmen, Lindsay, came and went in only a handful of pages, yet their essence is captured beautifully. Simple moments—like how Reed, a hitchhiker on Sean’s journey back to Colorado, always calls Sean “boss;” or the way he describes his girlfriend, “Pure Cuban. All her family crossing over on a boat hardly more than a raft”—give us a hint of Reed’s past and societal views in two short sentences. Johnston is able to create such nuanced minor and major characters through the use of dialogue and action, never falling into the trap of static stereotypes.

For many people, especially those who grew up near them or spent a time around them, mountains take on a persona of their own. They are mysterious, ominous, and yet beautiful and wondrous all at the same time. Much like the complexities Johnston creates in his human characters, the mountain is a character in itself with strengths and flaws. The title itself says it: Descent. This is a story of getting down that beast, the ultimate antagonist. “The wind plays a cold note in the boughs of the trees, in the needles; the sound of absolute aloneness. She moves forward and the mountains move together and she is under trees again, their laden arms dragging against her, the snow spinning up from the ground and littering the backside of her lenses with a distorting rash of crystals.” Johnston has given the mountain music, movement, and intention. But the many-faceted mountain can also be a friend. As Caitlin works to corrode the chain on her ankle, it is the crunching of mountain snow that tips her off that her captor is returning, a sound that saves her on many occasions.

Tim Johnston has crafted an intricate novel in which the reader gets to enjoy real characters in surreal and tragic situations. There is nothing more refreshing than experiencing human beings who act like human beings. And in the end, Descent is a story we all need to hear as Johnston dedicates the book “to your daughters, and to mine,” with Caitlin’s chilling warning “this could happen to you.”

About the Reviewer

Malissa Stark is a freelance writer from Colorado currently living and working in Chicago. Her book reviews have been published in Bookslut and the Review Lab, as well as Colorado Review. Her work can also be read in Eco News Network, the Story Week Reader, and Crack the Spine, among others. She also serves as associate editor of the Publishing Lab, an online resource for emerging writers.