Book Review

In 1970, the Jargon Society published the The Poems of Alfred Starr Hamilton. At some point in the 1980’s, I stumbled upon a copy. It is a beautiful book, with thick paper in alternating signatures of off-white and lavender. There are pen and ink drawings by Philip Van Aver sprinkled throughout. This book was a happy secret; it was incredibly hard to find copies of it. I would bring it out to share with the occasional friend, and occasionally that friend would already know about Alfred Starr Hamilton, whereupon we’d put our heads together over the book and shiver in pleasure.

In 1970, the Jargon Society published the The Poems of Alfred Starr Hamilton. At some point in the 1980’s, I stumbled upon a copy. It is a beautiful book, with thick paper in alternating signatures of off-white and lavender. There are pen and ink drawings by Philip Van Aver sprinkled throughout. This book was a happy secret; it was incredibly hard to find copies of it. I would bring it out to share with the occasional friend, and occasionally that friend would already know about Alfred Starr Hamilton, whereupon we’d put our heads together over the book and shiver in pleasure.

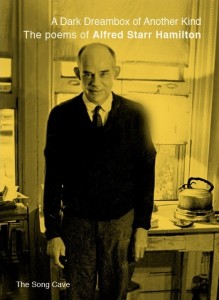

Alfred Starr Hamilton’s poems are now an open secret thanks to the good work of The Song Cave which has recently printed A Dark Dreambox of Another Kind, an extended collection of Hamilton’s poems. Among other things, this is a miracle of retrieval. As Ben Estes’s and Alan Felsenthal’s introduction notes, Hamilton was a prolific writer (for many years, he submitted about 45 pages of poetry by mail each week to Epoch Magazine) and of “all the thousands of poems he was known to have written, each was typed up a single time—with no duplicate.”

That Estes and Felsenthal have sifted through such a mass of work, including Hamilton’s late and shakily written notebooks, is reason for gratitude. It is also worth reflection as to what this means about the poetics enacted in A Dark Dreambox. Hamilton subsisted on a tiny inheritance, living in a rooming house in New Jersey. The evidence suggests that what he did was make poems, and that he did little else. The poems are strange, and they are not always “good.” Sometimes they are clunky and redundant like the best efforts of an ardent grade-school poet.

Utterly earnest, their grammar and logic can strain attention. Consider this first stanza of “Tampa, Florida”:

To sting a centipede around

A pineapple bend, on a peach—truth is

Studied on the breast—abysmally

To my reading, the density of thought, while intriguing, doesn’t quite add up to a satisfying experience. Yet it is an experience. Hamilton’s writing models poetry as experience and process: in the Starr Hamilton universe, poetry is a vast expanse of perception that wrestles to attain form, maybe to impose form, but its greater purpose is to ride that experience through various tides. This is the difference between career and vocation. Hamilton made poems that followed the call of vocation. While reading his poems, one sometimes feels as if the voice that called him little heeded traditional markers of craft or intelligence. Instead, there’s something more than a bit uncanny in these poems. As Estes and Felsenthal aptly state, these poems are “the product of encountering a world while staying away from it.”

If the remove between the concrete, conventional world and an intensely lived poetic world can make for bumpy moments, it can also alter all of our worlds suddenly with the snap of parts fitting together in ways that one would have been sure they simply could not do. Here’s “Blizzard”:

moreover

creeps over

the barren astonished earth

moreover that is a cat’s white velvet claw

that can have been named after the white and drifting snow

As this poem may suggest, Hamilton’s poems seem made up of equal parts compulsivity and grace. Most often his poems are constructed around a repeating word or phrase, relying on the durability of litany and chant as a mode of order within an unstable and apparently lonely interiority. Hamilton will fasten onto a word and then lean hard on it. The pressure yields the inner malleability of the word, so that the bird “cardinal” may become clergy “cardinal,” for example, or “ink” may become “inkling.”

In “Blizzard,” one can see this form of movement at play in the repetitions of “moreover.” Each instance of the word functions differently (once as a seeming noun and once as a conjunction). This repetition rhymes with “over” and knits with the soft “r” sounds that recur in “creep,” “barren,” “earth,” “after,” and “drifting,” which are set off by the interrupted alliteration of “cat’s,” “claw,” and “can.” This sound play, combined with the gorgeously improbable image of the “white velvet claw,” and the larger metaphor set off by the title, demonstrate both the compulsive ordering that Hamilton works through repetition and the way the poem is able to leap through and above that structure to find something of its own.

The leap is a form of transposition and transformation: “I revered/I was reverent/I revered postage stamps”; “I ventured beautific (sic) dreams/I ventured enchantments/I ventured further than I could.” Transposition and transformation may be part of a leap that acknowledges limits (“I ventured farther than I could”), but that is a part of the grace of the poem. Elsewhere, Hamilton asks, “Are you a fierce nomad?” You have to be fierce to write, and perhaps even read, these poems. They follow the call they hear. They are trustworthy but not reassuring. Hamilton shows us how stumbling is a necessary grace.

Reading these poems, I have wanted to find a way to express the pull they exert over me, but a review is not sufficient for that task. Preparing this review, I found myself frequently pausing to read them aloud to my 18 year old son Wilson, with whom I was traveling.

One day, I read “Sky and Purposes” to him:

I know this is colossal

I know this is possible

I know I can do it

I know I can do it again

I know I can do it again and again

I know of a big cloud that is shaped for an elephant

I know of a little cloud that is shaped for a peanut

I know of pushing the little cloud over to the big cloud

I know of putting the peanut onto the elephant’s trunk

When I finished reading, my son paused and looked thoughtfully into the distance. I thought he was searching for a polite way to tell me to stop interrupting him. Instead, after a moment, he turned to me and said, “You know, Alfred Starr Hamilton might be my favorite poet ever, because his poems make sense in a kind of a way, though I don’t know exactly what that sense is.”

About the Reviewer

Elizabeth Robinson is the 2013 Hugo Fellow at the University of Montana. Her most recent book is Counterpart (Ahsahta, 2013). On Ghosts, a hybrid poetry/lyric essay book is forthcoming from Solid Objects. Robinson is a co-editor of Instance Press and a new magazine, Pallaksch.Pallaksch.