Book Review

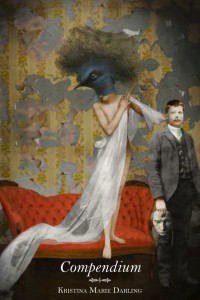

Compendium means a concise treatment of a vast subject, and this small volume (six inches by four inches, the size of a postcard) from Kristina Marie Darling is aptly named. However, the emphasis in a conventional compendium or abridgement is on including information so necessary and salient that gaps and omissions aren’t obvious, while Darling’s book calls attention to what’s excluded. There is more white space than print in its fifty-five pages. It includes a series of footnotes to missing texts and ends with a brief “Introduction to the Lyric Ode.” The book does not contain a table for its contents, though it opens with a table of contents of sorts, a work entitled “Palimpsest” (a palimpsest being a text where earlier writing has been erased to create room for another text, though the earlier writing often shows through). Each of the six chapters outlined in “Palimpsest” is labeled “Chapter One,” though they discuss a story in medias res. The six works that follow, titled “The Box,” “The Blue Sonnets,” “The Lockets,” “The Homage,” “The Dress,” and “The Elegy,” are each paragraph-long prose poems featuring a woman named Madeleine and a man known only as “the connoisseur”; they inhabit a lonely, large house where he writes poetry and entertains guests while she listens to music (the source of which is not made clear) and serves as some sort of muse. A relationship and a narrative are both hinted at, but the connections that would provide a clear sense of what actually happens are among the things that have been omitted.

Compendium means a concise treatment of a vast subject, and this small volume (six inches by four inches, the size of a postcard) from Kristina Marie Darling is aptly named. However, the emphasis in a conventional compendium or abridgement is on including information so necessary and salient that gaps and omissions aren’t obvious, while Darling’s book calls attention to what’s excluded. There is more white space than print in its fifty-five pages. It includes a series of footnotes to missing texts and ends with a brief “Introduction to the Lyric Ode.” The book does not contain a table for its contents, though it opens with a table of contents of sorts, a work entitled “Palimpsest” (a palimpsest being a text where earlier writing has been erased to create room for another text, though the earlier writing often shows through). Each of the six chapters outlined in “Palimpsest” is labeled “Chapter One,” though they discuss a story in medias res. The six works that follow, titled “The Box,” “The Blue Sonnets,” “The Lockets,” “The Homage,” “The Dress,” and “The Elegy,” are each paragraph-long prose poems featuring a woman named Madeleine and a man known only as “the connoisseur”; they inhabit a lonely, large house where he writes poetry and entertains guests while she listens to music (the source of which is not made clear) and serves as some sort of muse. A relationship and a narrative are both hinted at, but the connections that would provide a clear sense of what actually happens are among the things that have been omitted.

That’s not necessarily a problem in a volume of poetry, where interesting and evocative language can take precedence over other literary concerns. Certainly the significance of individual lovely, striking words or objects is highlighted in the second section. It consists of six untitled, extremely brief poems composed by excising all but a few words of each prose poem about Madeleine, as in

The most somber green taffeta

adrift.

An elegy with starched skirts.

It’s a clever and interesting move that may also underscore some weaknesses in the language of the longer poems. As lovely as individual words and phrases might be, as beautiful as the scenes they’re describing, the syntax and tone of the book threatens to become uniform. Most of the poems describe elegance and passion; the language is accordingly elegant, but strangely lacking in passion. Objects are imbued with greater significance than interaction between human beings. Fragments are used as a way to create mystery and carry a moment to its end while preventing closure, as in “Snow falling outside the great white house as she danced and danced” or “Her music drifting farther into the cold blue arms of that evening” or “Even the grandest arcades leaning towards her.”

Intrigued by Darling’s interest in format, omissions, white space, silence, and gaps, I read the book several times, hoping that its silences would also gain eloquence. On each reading, it was an immense relief to finally encounter, in “An Introduction to the Lyric Ode,” the very last poem, a few questions interspersed amidst all the beautiful description:

b. “And it was only then that the most unusual bird would emerge, singing.”

Where, exactly? And how?

“In the meadow. It was when you were sleeping, so the thistles were out of season.”

But what sort of event was it, precisely? I don’t understand the occasion, or the light catching in every darkened window.

The questions were a relief both because they offered a break to the uniformity of Darling’s other sentences and because the text’s elegantly dispassionate declarations and descriptions deserved to be questioned. If, as we read on page 25,

It was never

the lockets

then what was it? The coy five-word denial comprising an entire page might point to an affirmation or a presence elsewhere, but it doesn’t seem to. This is an interesting experiment by a writer with a genuine gift for beautiful language, but a beauty somewhat tempered by so much attention to what is excluded and so little attention to what remains.

If this is a “compendium,” what vast subject is it a brief treatment of? With references to madness, melancholy, the Victorian novel, a history of desire, multiple invocations of Orpheus and Eurydice, as well as a relationship between Madeleine and the connoisseur that precipitates the writing of a whole series of sonnets and the contemplation of the elegy, it seems reasonable to posit this as a compendium of passion. Strong emotions are frequently mentioned, but never recreated or aroused. I struggled at times with the book’s paradoxical work of passion and passion’s lack. Compendium is nonetheless interesting and promising. Given how much Darling accomplishes while working with such a limited range, it’s exciting to imagine what she’ll achieve if she broadens her syntactic repertoire, and worked to create in her pages that passion she is so apt to describe.

About the Reviewer

Holly Welker’s poetry and prose have appeared or are forthcoming in such publications as Alaska Quarterly Review, Best American Essays, Bitch, Black Warrior Review, the Cream City Review, Hayden’s Ferry Review, Hiram Poetry Review, Image, the Iowa Review, the New York Times, Poetry Northwest, the Spoon River Poetry Review, Sunstone, and TriQuarterly. She currently lives and writes in northern Utah.