Book Review

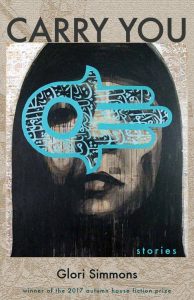

In 2003, along with millions of people around the world, I tried to stop our country from going to war with Iraq. I marched, I chanted, I waved signs. I protested nonviolently. I was arrested. Nothing worked. Now, fifteen years later, in spite of the war officially ending in 2011, we are still fighting in Iraq—a fact so mind-boggling I had to Google it to be sure. The war has continued for so long now that an entire generation has never known a time that we didn’t have soldiers in the Middle East. It’s depressing and easy to forget—two reasons (but not the only reasons) that Glori Simmons’s latest story collection, Carry You, is so important.

Simmons’s collection contains eleven linked stories that follow two middle-class families throughout the war. One family is Iraqi, the other American. The Iraqi family suffers power outages, militias, car bombs, kidnappings, deaths, ransoms and more. The American family suffers PTSD, addiction, and wounds collected from combat. These are two sets of experiences from two sides of an ongoing war, but it is not that simple. Simmons shows us that, as in war, the two sides do not remain fixed on either side of a declared line. Instead, the two families become increasingly intertwined with each subsequent story, impacting one another in inescapable ways.

The Iraqi stories shine with a special brilliance, not in detailing the horrors of war—though Simmons does this too—but in humanizing the families we have been bombing and shooting for more than a decade. The scenes that detail Baghdad before the 2003 invasion show a sophisticated urban world totally at odds with the rubble-strewn images we have come to know. Take this description as Sahar Khalil leaves one morning for her job as a museum curator:

She shook a cigarette loose from the pack she kept hidden in her glove compartment and slipped it between her lips. She pushed in the lighter and then a Best of Streisand cassette, adjusting the levels so that the American’s strange nasal voice came through the back speakers. She cracked open the top of the window and blew out her first puff of smoke. Every move was steeped in ritual. On the boulevard, she sang with Babs, sometimes even cried.

We learn of Sahar’s family, her husband, her children, and her disapproving mother-in-law, and although war descends on her family with ultimately horrifying consequences, Simmons portrays the character of Sahar as a complex human being who finds joy, even in the midst of occupation: “She’d just left a museum event and felt giddy. Her keychain jangled as she swerved around the potholes created by IEDs and Humvees.” Only later, when Sahar’s daughter Leila goes missing, does Sahar’s life begin to truly unravel.

The Iraqi stories alternate with the American stories, which follow Clark, a man who enlists in the Army, gets injured by an explosive in Baghdad, and returns home at age nineteen for the shrapnel to slowly and painfully work its way from his legs. Despite his injury, it’s difficult to feel sorry for Clark—he does some pretty despicable things in Iraq, he hits his fawning girlfriend when he returns home, and he spends too much time cleaning his father’s rifle in front of the TV. Yet, in the end, he too is suffering, a living reminder of the ways in which war destroys the occupier as well as the occupied. Simmons, however, does not alternate chapters in an attempt to portray Clark on equally sympathetic footing as Sahar’s family. On one hand, we cannot objectively judge and compare the suffering of different people. On the other hand, who are we kidding? Clark’s mental and physical wounds pale in comparison to what the Khalils have experienced. Yes, young men like Clark were sent to Iraq based on a lie for geopolitical ends. Yes, they have been largely left to fend for themselves when they return. But Clark volunteered to go abroad. Those were his boots on the ground. He held the heavy weaponry. He held the power while the Khalils held none. By making this distinction, and not trying to write Clark as a wholly “likeable” character, Simmons breathes a true realism into the collection that makes it spark.

Were the collection to end here, it would still remain a fine example of war fiction—two separate narratives loosely braided in a geopolitical way. Nevertheless, Simmons tightens the collection further, using Leila’s disappearance as the engine that unites Carry You and links the two story lines on opposite ends of the globe, ultimately leaving us with a book that is more of a novel than a story collection. In Iraq, Leila’s father crisscrosses Baghdad with photographs of his daughter, frantically searching for information. On the other side of the world, in eastern Washington state, Clark is weighing suicide against redemption. One small way in which he can redeem himself involves an object passed to him by a young Iraqi woman moments after a marketplace explosion. What Clark chooses to do with this object will have ramifications far beyond his orbit.

After reading Carry You, I typed the beginning of a query into Google— “Are we still . . .”—and its autocomplete finished my question with the following suggestions, in order:

Are we still in an ice age?

Are we still friends?

Are we still at war with Iraq?

Clearly I’m not alone in wondering if it is truly possible that we still have a military presence in Iraq. The consequences of that invasion continue to be played out, resulting in statistics so large and awful that it can be difficult to process. Fiction, done right, can do the important job of making real the vague and overwhelming—a task successfully achieved by Glori Simmons in Carry You. A detailed and complex portrait of the war on both sides, Carry You is an important reminder of the terrible ways that war can—and does—go wrong.

About the Reviewer

Nick Fuller Googins’s fiction and poetry has been read on NPR's All Things Considered, and has appeared in the Southern Review, Ecotone, Narrative, ZYZZYVA, and elsewhere. He lives some of the time in Los Angeles and some of the time in Maine. In his spare time, he installs solar panels and plays trombone as the least talented musician in an activist street band.