Book Review

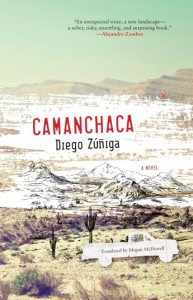

Not until the last page of Diego Zúñiga’s novel Camanchaca does a camanchaca itself appear. Camanchacas, a Chilean phenomenon, are banks of clouds that form over the Atacama Desert and produce a dense, dry fog. If you search for the term online, you can see pictures of them enveloping the bases of ridges and of mountains as if the peaks actually reached into the stratosphere.

Not until the last page of Diego Zúñiga’s novel Camanchaca does a camanchaca itself appear. Camanchacas, a Chilean phenomenon, are banks of clouds that form over the Atacama Desert and produce a dense, dry fog. If you search for the term online, you can see pictures of them enveloping the bases of ridges and of mountains as if the peaks actually reached into the stratosphere.

Most of the novel Camanchaca indeed takes place in and around the Atacama, which stretches over northern Chile. The story alternates between bits of an unnamed narrator’s fractured life. He spends most of his time with his mother, who is still distraught over her separation from the narrator’s father. But he also visits his grandfather, a Jehovah’s Witness who makes frequent comments about the narrator’s weight, and his father, an obtusely happy man who listens to Pat Metheny.

Now twenty, the narrator was four when his parents split. His mother descended into penury while his father was eventually able to purchase a BMW; she remained single and desperately lonely while he married and had another son. The narrator’s mother pushes him to persuade his father to buy him as many provisions—especially clothes—as possible. Meanwhile, she is too poor to do anything about their dying dog, Coka, who is constantly whining in pain. (Cruelty to animals—among them dogs and sea lions—is a motif here.) As a result of his frenetic existence, the narrator has become deadened to his surroundings. He jams his headphones on when he gets into the car with his father and absconds into a book when he is at his grandfather’s house. And while he is intelligent—he wins scholarships for college—he still blows his university stipends and meal vouchers as soon as he gets them. With a life empty of truth, he searches for things to fill himself up; in a particularly low moment, he leaves the house with one thing in mind: “The most important thing right then was to eat something big, something that would hold me over until very late.” Consuming, for him, has become therapeutic, perhaps a way to access both his father’s spending and yet return to his mother’s poverty.

As the title hints, there is a fogginess to each character, and certainly to the events preceding the novel. Take, for example, the death of the narrator’s uncle Neno, who, we learn on the first page, was killed by the narrator’s father’s BMW. Or take the mysterious family circumstances that led the narrator’s mother’s refusal to ever return to Iquique, a coastal town near the Atacama. Or take the fact that the narrator’s mouth bleeds. What is wrong with his mouth? Why is Coka sick? What happened between the narrator’s parents? Why does an image of the narrator’s mother “facing away . . . her back red and sweaty” come to him in the dark house?

The successive pages of Camanchaca keep raising questions and deepening mysteries. Its vagueness is occasionally maddening, at least until one realizes the answers aren’t the point. The narrator is as ignorant as the reader about events like what happened in Iquique: “I know my grandpa will start talking now about why we left Iquique like that, so rashly, and I won’t know what to tell him.” Eventually, the narrator himself resigns to the fog and doesn’t press his father for answers.

There is nothing foggy in the writing, however—or in the translation. Megan McDowell—who has translated Álvaro Bisama, Lina Meruane’s outstanding Seeing Red, and works by Alejandro Zambra, among others—provides another lucid and direct rendition. The novel is episodic, swinging from the past to the present, with no bit lasting longer than a page. The effect is poetic, and Zúñiga’s bare sentences also resemble the Atacama: “The color of the sky: orange, maybe purple at times. The desert: blue, as if a blanket were covering it. There is nothing.” The purpose of these episodes is perhaps analogous to strategy of a boxer intent on jabbing, jabbing, and jabbing, in preparation for the haymaker.

Zúñiga is an author and journalist. Camanchaca is his first novel, and his first work to appear in English. He seems to fall within a burgeoning wave of Latin American writers producing short and evocative novels that are trickling into English thanks to independent presses. Like Bisama’s Dead Stars or Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream, Camanchaca leaves its readers with a bitter taste. Its denouement—its haymaker—verges on the ethereal. Ultimately, the only thing truly unexplainable is what to make of the past. Events are one thing, but when you try to make sense of them, the fog creeps in.

About the Reviewer

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Midwestern Gothic, The Millions, Necessary Fiction, Palooka, and Pulp Literature, among other sites and publications. He lives in Lincoln, Nebraska, with his wife, daughter, and Yorkshire terrier.