Book Review

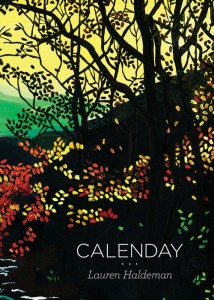

Calenday is a tiny pocketbook collection of days and moments, of time spent and time lost. Physically, it fits in the hand like a personal day planner or notebook, with textured pages that remind us to touch life back as it touches us, for better or for worse. This is the first full-length collection from Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum Lauren Haldeman and yet her voice is one of experience, rugged at the edges and unapologetic in its inquiries.

Calenday is a tiny pocketbook collection of days and moments, of time spent and time lost. Physically, it fits in the hand like a personal day planner or notebook, with textured pages that remind us to touch life back as it touches us, for better or for worse. This is the first full-length collection from Iowa Writers’ Workshop alum Lauren Haldeman and yet her voice is one of experience, rugged at the edges and unapologetic in its inquiries.

Haldeman explores the impossible task of learning to parent a newborn, the shock of how a “whole body came out of my body.”The simplest tasks of feeding and soothing come without instruction: “The cat put its butt / in your face. My milk got in your nose.” Children enter this world without a manual for the ordinary task of existing alongside parents who are out of their element until a familial rhythm is earned, a trust for one another is built, and “Someone sleeps // & it is quiet.”

The speaker alienates adult and child in the matrix of new parent and new person, demonstrating wonder in each experience and coming to understand “The reason she came from / outer space.” Before the baby, there was no baby. After the birth, the mother is no longer independent within herself, the speaker expresses, as she comes to know “My human,” as an extension of her own self.

These experiences are so full of wonder for a new parent that the poet transforms observations into poetry—writing poetry about writing poetry about these experiences: “If I were told to start a collection, and it / seemed wise to start a collection, and everyone else was starting a / collection, I would start a collection of you.” In this prose poem, “05/09,” the poet employs a microcosmic approach to understanding her world, which consists of poetry and a baby. Yet in this small-scale version of the universe, these two objects of her affection are the whole world, and the most important world to write about.

As the mother finds a groove in her new roles—“I’m your mom, I am // astronaut, helmeted raven; I am neutrons, plum-pits”—she begins to understand that “We don’t get older, we just / get more detailed” as life shifts from one detail to the next. This is where Calenday begins to curl inward on itself as the poems drift from parenting to other experiences of life—memory, grief, and confusion. Where a parent once expressed wonder at a new life developing outside of the womb, now “Fog was born from a room” and the narrator reflects upon how something could be present that only a moment ago was not. “Fog is hard to explain,” she muses; like life, “Fog just is.” In this way, life is paralleled with death, existence with nonexistence.

For some things, the speaker comes to realize that there is no explanation, no middle ground, yet the compulsion to ruminate about life’s intricacies carries on in microscopic analyses: “Feeling bad forever and then // it is finished: no more feeling bad.” The complexities of motherhood span from joy to frustration as the narrator contemplates curious child behavior even while admitting “the feeling of trapped lion inside me.” This emotion comes alive as the parent witnesses the child developing a personality outside of the mother and away from the parent, and this division promises both a future and a loss of what once was. While the parent can envision a child’s future adult face, the parent must redefine herself and reacquaint herself with who she was and who she is now: “I leave a mark / to track myself later.” Yet even while the narrator tries to regain a sense of who she is independent of her child, she is only just beginning to understand loss.

The second half of Calenday takes a turn toward confronting death—specifically, the death of a brother—and the speaker’s reflections are a means to coping with loss, of keeping a memory alive, and in giving the self permission to accept what must be accepted. In the poem “Courage Courage Courage,” the narrator speaks directly to her brother, as she fumbles with knowing what to say or what may be heard: “My letters to you begin with your name and then I am lost.” For all the wonder the parent experienced in seeing a life develop in and then outside her body, she is equally bewildered with how death happens within us: “What is true about dying? It happens / Afterwards you don’t know it happens.”

It is no accident to pair a section of poems about birth with one of death. One contains curious joy, the other fiery heartache, yet each section of Calenday interweaves with the other, like “Distances evolving between you & your date of birth.” For all the raw emotion the speaker expresses in figuring out a new life, she lends the same passion to deconstructing how a life that once was is no longer.

Calenday is a calendar of days, of life events, but it is not one that was planned. Life doesn’t work that way. Haldeman’s poems examine the intricacies of the unknown, the unexpected, and share a first-person diary of shifting when the earth moves, holding steady when the wind dies down. These are poems of strength and courage and grace.

Published 5/19/2015

About the Reviewer

Lori A. May writes across the genres and drinks copious amounts of coffee. Her writing has appeared in The Atlantic, Brevity, and Midwestern Gothic. Her sixth book, The Write Crowd: Literary Citizenship & the Writing Life, was published by Bloomsbury in December 2014. She lives online at

www.loriamay.com.