Book Review

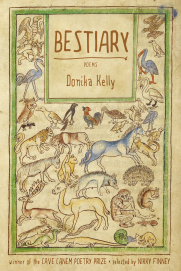

A ‘bestiary’ is a collection of beasts emerging from a long history of collecting data on animals both mythic and real. Perhaps the first bestiary was the Greek Physiologus, compiled around the second century, which catalogued beasts from literature and other accounts, blending anecdote, story, and description. In Donika Kelly’s Bestiary, winner of the 2015 Cave Canem Poetry Prize and longlisted for the 2016 National Book Award, the reader is presented with a catalog of Kelly’s life through rhythmic, fine-tuned poetry. It is a place where animals become human, humans become animal, and monsters lurk within and without the body.

Kelly invokes Lucille Clifton’s “Moonchild” in her poem, “Fourth Grade Autobiography” through the father’s “Midnight walks from his room to mine. / I believe in the devil.” The poem transforms and catalogs the family: mother, two daughters, a brother, the dog. It catalogs the house as well, but it slips between these concrete memories an “anvil” that orbits like Clifton’s moon, “Sometimes my dad dances with me. I am / careful not to touch. He is careful / to smile with his whole face.” The mother, too, is shadow, a memory repeated but often like the turn of the tide, present and aching. Torn is image of parent as protector, replaced with the doll, the memory, the shadow.

In “Self-Portrait as a Door,” Kelly shows a deft hand at use of rhythm, the anapest the only break in a series of hard-stressed lines that roll cyclically like a knock on the door that keeps knocking, perhaps connecting back to that autobiography: “There is a hand hard as you are hard / pounding the door.” Then, the hand is masked, a body within a body in the poem “Handsome is.” The father transforms and we retreat with the poem deep inside the self, and further even, “inside the earth.” Kelly connects everything back to the earth and natural elements which helps to ground the darker corners of the mind, but also allows for flight.

The bowerbird, unique in its intricate manner of courtship, builds bower-nests decorated with brightly colored shells, bits of plastic, shiny material, leaves, flowers, whatever might attract a mate. He “manicures his lawn,” selecting the bluest pieces, but when the female “finds him, lacking. / All that blue for nothing.” Kelly’s “Bower” series of poems about that same bird never resolves itself, but the bird transforms in the third iteration, in which the human body becomes both nest and bird. The clothes become a decoration of both identity and a reimagining of the female body. From “Bower”:

this ill-fitted hat. These boy things.

These men things. This hurried

disrobing. My ashen body

and untrimmed nails. But who will listen

to the song of a nutbrown hen?

The birds are a repeated image in Bestiary—a red bird, a swallow, a brown hen, pulp, feather, wings unfurling. The bird takes flight, calls, can be crushed in a hand, and can build a bower for its lover.

The love poems are also entries in the bestiary, taking on the more mythic creatures, the centaur, satyr, mermaid, and werewolf, each a shedding of skins. In “Love Poem,” the penultimate poem of the book, humans become both fish and fowl: “We iridesce / orange and green and shred the flannel / with our thrashing.” Donika Kelly’s debut book becomes an itemization of what we see in ourselves, and of the earth around us. The words are in the trees, sea, and sky, but also in the deepest parts of our shadow selves. Kelly’s sentimentality is distorted through trauma, but it is that distortion that draws us in:

I tell you, between gritted teeth, of my life as a tree:

How tall I was.

How brown and green.

About the Reviewer

Jennifer van Alstyne has been published in the Eunoia Review, Midwest Literary Magazine, The Monmouth Review, The Foundling Review, Paper Nautilus, Poetry Quarterly, and Whiskey Traveler, among others. Her collection, Scansioned Music: A Glenn Gould Collection, was published by Crossroads in 2013 for which she was the winner of the Jane Freed Grant. She holds an MFA from Naropa University where she was the Jack Kerouac Fellow. She is currently a graduate fellow in Linguistics at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. She is an Associate Editor for Something on Paper, a journal of poetics and pedagogy.