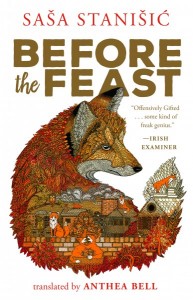

Book Review

Who writes the old stories?

Who takes that job on?

From the opening lines of Saša Stanišić’s Before the Feast, the reader sits as if at the feet of the novel’s storytelling narrator, the first person plural collective voice of a village. “We are sad,” the village laments. “We don’t have a ferryman any more. The ferryman is dead.” With that, we readers are sent to some mythic ferryman-incorporating past, only to be yanked back to the present further down the first page. By the banks of a lake where the ferryman once rowed, “there’s a fridge stuck in the muddy ground, with a can of tuna still in it.” The can of tuna, we learn, made the ferryman angry. This push and tug of past and present, myth and precise contemporary detail, create a sense of slippery links between story and fact that pervades Before the Feast.

Who was the ferryman? The ferryman rowed villagers and tourists across the Deep and Great Lakes, often for stories instead of a fee. The ferryman existed in all the village’s ages, rowing Angela Merkel in the present-day and the devil in a previous era. “He didn’t belong in this time,” thinks Johann, the village’s sixteen-year-old apprentice church bell ringer. “The Middle Ages would have been a good time for him.” Who was the ferryman to the village? Not a Charon to ferry the dead—or at least not foremost—but a ferryman who described the village to itself. The village posits: “Who but a ferryman says things like, ‘Where the lake laps lovingly against the road,’ and ‘It was tuna from the distant seas of Norway’ so beautifully? Only ferrymen say such things.” What happens to a village heavy with stories when its recounting ferryman drowns?

It appears the village must carry on telling its stories, which it does on the night before the so-called Anna Feast, held every September. “No one really knows what we’re celebrating,” the village tells us. “Perhaps we’re simply celebrating the existence of the village. Fürstenfelde. And the stories that we tell about it.” Before the Feast is not the choral story of “Our Town” but of “Their Town.” The village’s “we” does not include us.

That is, unless the reader happens to have grown up in rural northeastern Germany. It turns out that Stanišić’s Fürstenfelde can be precisely located on Google Maps, its name barely changed: Fürstenwerder, a village on a spit of land between two lakes in the Uckermark region and the state of Brandenburg, eighty-five miles north of Berlin and forty miles west of the Polish border. In Stanišić’s telling, Fürstenfelde is charged with the same specificity of location and details mingled with history and legend.

Who are the villagers telling us Fürstenfelde’s stories now that the ferryman is dead? There is Frau Schwermuth, “our chronicler, our archivist,” swollen and burdened with stories, who is watching Buffy the Vampire Slayer while eating baby carrots the evening before the Feast begins; her son Johann the apprentice bell ringer, who listens on his headphones to the British band The Streets and their song “On the Edge of a Cliff,” about the generations who have come before and given us the gift of life (“What are the chances of that like?” sing The Streets); old Imboden, who tells stories of “the old days,” by which he, “like everyone else, always means the entire time before the Wall came down”; Uwe Hirtentäschel, the village’s prodigal son, once drug-addicted and away from home, now back and the village’s pastor; the elderly Frau Kranz, who paints pictures of the people of Uckermark and, like Stanišić himself, fled her home in Yugoslavia as a child due to war; Herr Schramm, a retired former lieutenant-colonel in the East German National People’s Army, who toys with destroying himself the night before the Feast and succeeds in partially destroying a cigarette vending machine; a fox; and different Annas through the ages.

The night before the Feast is the last night in the village for the present-day Anna, who has grown up in a farmhouse, owned by generations of her family, which lies next to a fallow field. The field is rampant with weeds and wild rose brambles and has an oak tree at its center. Both field and oak tree return again and again: the fox runs through the field; Polish forced laborers recite poetry there during the War; Belorussians shoot dozens in the field; a “Gypsy gallows” stands there; once, mysteriously, in a time of great hunger, apples are found lying beneath the oak tree; the present-day Anna smells “cadaverine; the field has made a kill again, it gives and it takes away.”

A time-traveling duo of tricksters, speaking in rhyme and stealing in past and present, were once executed in that same fallow field. The night before the present-day Anna Feast, they dig up their own skulls near the oak tree, stick cigarettes in their skeletal jaws, and then bury them again. Or were they never executed but instead carried across the lake by the ferryman after they escaped their prison due to a fire in 1599? And are they the reason the village church bells are found by the shores of the lake on the morning of the present-day Feast?

And is Frau Steiner, who tromps through ancient Kiecker Forest wearing Globetrotter hiking boots looking for herbs and who recites not a prayer but an incantation in the early morning of the Anna Feast, really a witch?

The night before the Feast ends with some villagers as bewildered as we are about where the mortar and cracks between past and present are, between legend and fact, between story and experience. As the novel slides from the sixteenth to the twenty-first centuries and back again, moving between nonchronological excerpts from the village’s annals to the village’s present, the reader is immersed in a nebulous aura similar to the state between sleeping and waking, when one remembers a dream’s vague outlines and a few piercing details—like a can of tuna in a fridge by a lake and a cigarette clamped in a skull’s jaw. When one emerges from a dream to that half-awake state, it is often difficult to say what exactly made the dream significant. The same is true of Before the Feast. I am left with those details and many stories, but I am not sure I know what it means. Beyond this: a village’s past stories seep into its present.

The village has a Homeland House where its archives are kept. Currently on display are an exhibit of tile stoves and another of “everyday items from the time of the German Democratic Republic.” Regional cycling maps can be purchased. In the cellar of the Homeland House there is a room—climate-controlled and behind a massive oak door, locked electronically—called the Archivarium. What the room holds is something of an intriguing mystery to the villagers: “We are surprised that no stories are growing and proliferating around the room in the cellar. That sort of thing usually happens when we come across cellars, locked rooms and open questions. We take a historical interest in the nonproliferation of stories.” However, when Johann spends some time during the night before the Feast locked up in the cellar room, we find that, on the walls of the Archivarium, there are leather hangings dated September 1636 with undisclosed writing on them. “It’s a skin of stories growing on us,” says the village.

“SOMEONE. SOMEONE WRITES THE STORIES. Someone has always written them.”

About the Reviewer

Lisa Harries Schumann lives outside Boston and is, among other things, a translator of German to English, working on texts whose subjects range from penguins to poems by Bertolt Brecht and radio shows by the cultural critic Walter Benjamin and the radio pioneer Hans Flesch.