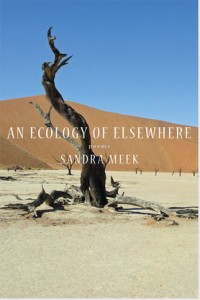

Book Review

Sandra Meek’s new collection opens with an ode to the Acacia karroo Hayne, a dense, bushy tree that can thrive in the arid conditions of southern Africa. Its long, white thorns come to vicious points; during the brief wars fought against the Herero in present-day Namibia between 1904 and 1908, German colonial soldiers stacked the tree’s branches as makeshift barbed wire. Meek’s ode walks an elegant tightrope between the beauty of the tree’s image and its sinister design. The thorns are compared to “the noteless stems of music a girl / scores into her arms.” Like the tree, the poem seduces us with a lovely—even saccharine—image, until we cross the white space of the page, and confront its bite. The human figure (the troubled girl) is employed not to anthropomorphize the tree, but instead as another vehicle in a string of metaphors that construct a perspectival view of this plant that “avoided pain/ by becoming its measure.”

Sandra Meek’s new collection opens with an ode to the Acacia karroo Hayne, a dense, bushy tree that can thrive in the arid conditions of southern Africa. Its long, white thorns come to vicious points; during the brief wars fought against the Herero in present-day Namibia between 1904 and 1908, German colonial soldiers stacked the tree’s branches as makeshift barbed wire. Meek’s ode walks an elegant tightrope between the beauty of the tree’s image and its sinister design. The thorns are compared to “the noteless stems of music a girl / scores into her arms.” Like the tree, the poem seduces us with a lovely—even saccharine—image, until we cross the white space of the page, and confront its bite. The human figure (the troubled girl) is employed not to anthropomorphize the tree, but instead as another vehicle in a string of metaphors that construct a perspectival view of this plant that “avoided pain/ by becoming its measure.”

This opening ode is in ways a metonym for the collection, which is constantly searching for vocabulary to capture the landscapes of Namibia which are at once picturesque and brutally inhospitable to human life. This is no easy task, particularly for a Western traveler who is often confined to experiences prescribed by the tourist industry and mediated by her purchasing power. “To be no one / in a country that doesn’t care to know you / is one version of home,” Meek writes in “Protea lepidocarpodendron (Black-Bearded Protea),” which chronicles the experience of her car being broken into in South Africa. Some of the most interesting moments in the book arise when Meek fully inhabits this conflicted position of the Westerner abroad, not apologizing for or diminishing the role, but staring unflinchingly at its problems. Applying the same close attention Meek gives to flora, “Protea lepidocarpodendron (Black-Bearded Protea)” details the car break-in, imagining that the burglar was a father. The poem ponders:

that second charge to the Cape Town

McDonald’s, the last to blink through

before my card cancelled: who you went back for

to feed, your confederates, or

your children

The poignancy of this question is heightened by an elegy to her own father that Meek weaves through the poem.

As might be clear from looking at “Protea lepidocarpodendron (Black-Bearded Protea),” Meek takes risks with these poems, testing the boundaries of her sympathy, whether for the human beings she encounters in their relative precarity, or for the fauna and flora that find means of existence in Namibia’s arid climate. Sometimes these interests—the human and the ecological—are opposed, and by exposing her sympathies so baldly, Meek leaves herself open to critique. The poem “Skeleton Coast” describes the hunting of baby seals off the coast of Namibia, ending with the baby seals’ plangent wails entering her ear on the shore:

voicing to sympathetic vibration

the three tiniest bones of the body

as if they might find there

anchor, safe harbor, some small welcoming

waving them ashore

The ear of the traveler here is a “safe harbor” from the savage fate the seals will face by the clubs of the hunters, whose activities (Meek adds in a note) the Namibian government has been unwilling to ban “despite the extremely modest income derived from seal hunting in relation to the real and potential income from seal eco-tourism.” Meek’s poem stages the difficult balance between human and ecological interests; while the notion of clubbing baby animals to death is unnerving, Cape fur seals are not an endangered species, and their hunting is a vital local industry. The collection moves through sympathies that, perhaps by their structure, cannot be easily reconciled, revealing possible bias even as it works to confront the same.

The poem “Kill,” which centers around a wave of xenophobic attacks in South Africa in 2008, also tests the boundaries and contours of sympathy. The poem describes the attacks directly in a long note in the back of the book; its body is instead centered on wild dogs in Kruger National Park eviscerating an impala, their “paws tucked / in the torso’s broken bowl as they strip // the steaming meat.” In the context of a book that is constantly reorienting metaphors that bridge human, plant, and animal, the implied comparison between the xenophobic attacks and the wild dogs’ meal is complex. Reading about genocides and war crimes happening continuously throughout the world can challenge the distinction between the moral conscience of humans and the thoughtless violence of animals; at the same time, by animalizing black violence, the metaphor aligns uncomfortably with a long history of white Western hubris. The poem ends with the speaker—still unfamiliar with the British colonial traffic system—turning her head the wrong way as she pulls onto the highway:

when I pulled back

onto the highway I caught myself

turning my head

as for a distant country, straining

to search the one direction

no one would be coming any longer.

This image of a harried, disoriented traveler turning her head the wrong way while steering into what may be a head-on collision may represent the affective confusion she has been thrown into by the news of the attacks. It is not pretty, but it seems honest.

The book explores its own inability to escape the legacy of Western colonialism, and the ways that the alleged moral imperative of ecotourism, when (as in the case of the Cape fur seals) used to sublimate the interests of the local community, can resemble the ideology of missionaries who flocked to southern Africa in the second half of the nineteenth century, helping to shore up political and economic power in the region while allegedly saving souls. The speaker of “Postflight Edema” addresses the legendary Scottish missionary David Livingstone:

But David, wasn’t it

sublime, how the crystalline sky seemed

to turn from the stylus of a thatched

roof’s cone as the village disappeared

into the darkness we made

to justify us; even the falling

stars cued each evening’s sweeping

swell of light, wasn’t it, wasn’t

it beautiful then, didn’t it feel just

exactly like home?

The speaker is caught in a bind, surrounded by the “darkness we made // to justify us,” haunted by a colonial present she can neither genuinely embrace nor fully disinherit.

Meek does seem to retain a faith, though, in attention to ecology as an ethical and aesthetic path forward for the Western travel writer in southern Africa. In a truly remarkable moment in the poem “Colophospermum mopane (Mophane),” Meek ironically inverts the relationship of traveler to landscape (whereby the tourist takes from the land) and imagines her photograph as a gift to the tree:

I’m standing you

to my camera’s

glass eye, leaving you

with this single

offering: a moment of pure

incandescence,

a flash of being

finally, fully seen—

Something for you

to remember me by.

The tone here is nearly impossible to pin down conclusively. Irony shimmers around the edges of Meek’s suggestion that the tree is only “finally, fully seen” when it is seen through the Western tourist’s mechanical aperture. But she seems committed to continue to look, alive to the limitations of her knowledge and sympathy, in love with the beauty of a place that may ultimately be hostile to her presence.

About the Reviewer

Sean Pears has lived in Boston, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. His writing and reviews have appeared or are forthcoming in Jacket2, Denver Quarterly, Colorado Review, NOMAN’s Journal, and other places. He is currently pursuing a PhD in Poetics at SUNY Buffalo.