Book Review

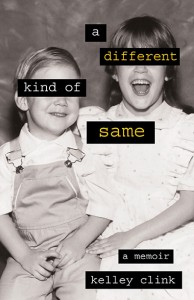

In 2004, weeks before he was due to graduate from college, Kelley Clink’s little brother, Matt, hanged himself. While his death was the culmination of a long struggle with bipolar disorder, it still came as a shock to those who loved him. Clink’s memoir, A Different Kind of Same, chronicles her grieving process over the course of several difficult years. The book is honest, brave, and soul-baring in its exploration of grief and clinical depression.

Though they were born three years apart, Clink and her brother shared an unusual sibling closeness and, as children, spent hours in each other’s silent company, communicating just by being near. In the memoir they seem more like identical twins than brother and sister. Clink perceived Matt as an extension of herself, an extra vital organ of sorts, but after his death she comes to understand that this sameness was a mirage, born of the tendency of children to project their own consciousness onto the people around them, unable to fully comprehend that each person experiences the world through a unique lens.

Clink’s slowly unfolding realization—that her long-held belief in her and Matt’s sameness was a fallacy—is what takes this memoir a step beyond the expected. Yes, the narrative recounts a terrible and sad personal tale, but it is not, to my initial surprise, Matt’s story. Instead, Clink chronicles her own experience of depression, set against this tragic death. So while she conducts informal research to better understand her brother—interviewing friends and relatives, and reading his journals, stories, poems, blog entries, and suicide note—the book contains only a small taste of her findings. In addition, she includes flashbacks of Matt only occasionally, making him feel like a ghostly presence rather than a fully realized person. But it was never Clink’s objective to paint a holistic, vivid portrait of her brother. Instead, the memoir is about Clink’s struggle with depression both as a teenager and in the wake of Matt’s death. This self-focus is not a flaw in the book, but its heart.

In typical families a little brother might copy his sister’s taste in music or books or even clothes, and Matt did copy Clink in these ways, but when he became mentally ill, Clink misinterpreted Matt’s bipolar disorder as yet another copycat maneuver. Blinded by the self-centeredness of youth, she failed to recognize that his illness was both different from hers and more severe. When he first attempted suicide a few years after Clink had, also by overdosing on psychiatric medication, her reaction bordered on egocentric annoyance. As she describes it:

I told him that I was disappointed in him for doing this, knowing what it had done to all of us before [when I made my attempt] . . . I waited to see a look of understanding, remorse. I waited to hear it all again, to see my sixteen-year-old self through my twenty-year-old eyes. I waited.

But he didn’t cry. He wasn’t sorry. Arms across his chest, eyes like wet steel. His face hard, removed, distant. No response. Only crossed arms. Only steel eyes. Only silence.

The more Clink accepts the distance that had actually lain between her and Matt and that they were more different than the same, the closer she is to healing.

The memoir moves in an appealing way between past and present and is broken into bite-sized, titled chapters in three sections: “Beginnings” (Clink and her brother’s childhood and their early struggles with mental illness), “Three Years” (her grief), and “Surfacing” (her acceptance of Matt’s death). The prose is readable and affecting. At times the narrative repeats itself, but not so much as to be irritating. It’s a challenge to describe how it feels to be depressed, especially when multiple, similar bouts of depression strike within a dozen years, and Clink’s descriptions of her various emotional experiences are keen and well differentiated.

Researching and recounting her brother’s story, voicing what had mostly gone unsaid in her Catholic, Midwestern family brings Clink catharsis. For her readers it is a sobering tale of how mental illness can rob a person of his or her life and leave in its place a path of guilt, regret, and confusion for loved ones to follow. Clink takes us down this path alongside her in A Different Kind of Same. It’s a painful journey, but we are the wiser for having seen it and joyous for her recovery. As Clink recounts,

The stories we told about Matt said more about us than they did about him. Mom wanted the cause of his illness to be pinpoint-able, concrete, and beyond her control. Dad didn’t want him to be ill at all. They told these stories out of love. Out of fear. Out of a need to keep him safe.

In this insightful memoir, the story Clink tells is ultimately not about Matt, but about herself—not in a callous or egocentric way—because whose story are we best qualified to tell but our own?

About the Reviewer

Jen Wisner Kelly’s stories, essays, and reviews have appeared in Massachusetts Review, Greensboro Review, Beloit Fiction Journal, Poets & Writers Magazine, Colorado Review, and others. She has attended residencies at the Jentel Foundation, the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts, and the Kimmel Harding Nelson Center for the Arts. She is the Book Review Editor for fiction and nonfiction titles at Colorado Review.