Book Review

Himmet Dajee begins his autobiographical tale in his youth, which is split between Cape Town, South Africa, and India. His life’s timeline is tracked by major events in the world, from his youthful realization of the apartheid system he was born into, to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, to the international community’s establishment of the Nuremberg trials. Amidst this backdrop, Dajee experiences his own upheaval. His mother dies while he is in high school. His eldest brother, Bhanu, vacates the family home and operates his own business nearby. He invites Dajee to move in with him, which is a welcome invitation as his father’s abrupt remarriage strains their relationship. Dajee also struggles academically for most of his youth, which is a constant self-deprecating theme throughout the early portion of the memoir and helps the reader to sympathize with his initial futile labor. Despite these challenges, Dajee endeavors to fulfill his dream to migrate to the West where he can be “free,” demonstrating his lack of awareness of racist institutions outside of South Africa. However, for a young Indian man whose world is limited for so many years by his father’s ideals and his brothers’ successes, the author manages to craft his own narrative of how he perceives his own life.

Himmet Dajee begins his autobiographical tale in his youth, which is split between Cape Town, South Africa, and India. His life’s timeline is tracked by major events in the world, from his youthful realization of the apartheid system he was born into, to the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi, to the international community’s establishment of the Nuremberg trials. Amidst this backdrop, Dajee experiences his own upheaval. His mother dies while he is in high school. His eldest brother, Bhanu, vacates the family home and operates his own business nearby. He invites Dajee to move in with him, which is a welcome invitation as his father’s abrupt remarriage strains their relationship. Dajee also struggles academically for most of his youth, which is a constant self-deprecating theme throughout the early portion of the memoir and helps the reader to sympathize with his initial futile labor. Despite these challenges, Dajee endeavors to fulfill his dream to migrate to the West where he can be “free,” demonstrating his lack of awareness of racist institutions outside of South Africa. However, for a young Indian man whose world is limited for so many years by his father’s ideals and his brothers’ successes, the author manages to craft his own narrative of how he perceives his own life.

His humble beginnings are wrought with anger as he confronts the daily reminder of apartheid enforced by primarily Dutch Afrikaners. Dajee expresses sympathy for black Africans who suffered much worse than Indians as a result of the apartheid caste system. The tone of the text changes, however, as Dajee recounts his time in Ireland and England where he begins to fulfill his dreams through rigorous academics.

Dajee acknowledges the two worlds that shaped his experiences as he pursues his professional medical career. Continental Europeans invite him into a world where he is respected for his intellect and talent, while Afrikaners humiliate and attempt to limit his and others’ quest for upward mobility because of their color and ethnicity. He discovers that some people, regardless of ethnicity and religion are good-hearted and kind. Their nature and understanding of what is right transcends the distinction or commonality of purported belief in doctrine or ethnicity. Meanwhile, others are of pure evil, even when they share a trait or belief system with those they seek to maim, slander, persecute, oppress, or even kill. Dajee seemingly reconciles much of these conflicting experiences when he states, “I would treat every patient in my care—young, old, black, white, rich, poor—as if that person were one of my own family.”

In spite of these intentions and his acknowledgement of the parallels between the apartheid system of South Africa and Jim Crow of the old American South, Dajee fails to address the racial discriminatory practices, micro-aggressions, and acts of violence of South Asians against Black Americans, which continue into the twenty-first century. Even as the author becomes a well-traveled and established medical professional, he appears to have never reached this level of dignified abhorrence against his ancestral India, whose cultural infrastructure and laws discriminated against him and his family, who admittedly hailed from a lower Hindu social caste. Perhaps this is because he spent much less time in the South Asian peninsula than in South Africa, where he witnessed the majority of violence for a substantial portion of his life before removing himself to the West. However, the omission of these parallels seems like a lost opportunity to illustrate the universal challenges of racial discrimination.

The rift between him and his father remains until his brief return to South Africa. Dajee candidly discusses how his father, who abandoned him in his time of need, now sees fit to tow him around the locals “… as if he was taking credit for my success”—a sentiment that will resonate with anyone who has endeavored to achieve a rarely pursued goal only to have those who scoffed, sabotaged, and disbelieved in their ability suddenly rally around when success appears to be on the horizon.

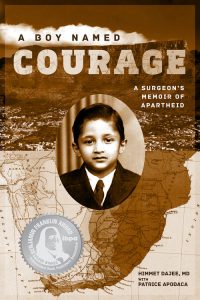

The theme of the heart, both physical and metaphoric, permeates the memoir. The reader may understand this as the interrelation of external events, a possible detriment to the human body, and the impact that these variables may have on the mind. For instance, at one point the author must address his father’s heart ailments. Although Dajee admits he never reconciled with his father, he acknowledges that without him he could have never persevered without the same obstinacy his father showed towards him and his family for so much of their lives. The author must also confront the mortality of his brother Amrit, who succumbs to complications from heart surgery. Dajee finally makes the decision to retire from medicine. His memoir is a truthful tale wherein he surmounts numerous barriers, endures copious rejections, and still evades the violence and inevitable death that South African apartheid generously offers. He carves his own path with help from strangers and often from his brothers, too. His heart becomes strained, just as his relationship with his father was for so many years, but he is able to endure. It is here that the author reveals that his name, Himmet, means “courage.”

About the Reviewer

Patricia M. Muhammad is an independent scholar in human rights law and restorative justice. She has currently published a combined nineteen academic book reviews and research papers which have appeared in the History Teacher, Columbia Journal of Race and Law, and the American University International Law Review, among others. She is also a fiction author of sixteen fiction book manuscripts, focused on sci-fi/fantasy, historical romance, and mystery genres.