Book Review

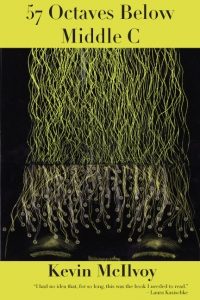

It’s said that the sound the universe makes is fifty-seven octaves lower than middle C. More specifically, it is a sound wave issuing from a black hole in the Perseus galaxy cluster. The escaping sound is low, lower, and lowest in one note, although no one can sing that note. Kevin McIlvoy, the author of the story collection 57 Octaves Below Middle C, is likewise, unique: I know of no one else who can sing his stories. They are always unexpected. It’s true that in recent years various authors have tried to find ways to write outside the box, but many fail in this endeavor. The human mind still longs to be logical and hopes for a reasonable, preferably favorable, reading. McIlvoy is the exception, his stories even stranger than those of Ben Marcus or Lydia Davis. So strange, sometimes, that it is difficult to put the story down. You may find yourself reading it over and over in search of meaning.

It’s said that the sound the universe makes is fifty-seven octaves lower than middle C. More specifically, it is a sound wave issuing from a black hole in the Perseus galaxy cluster. The escaping sound is low, lower, and lowest in one note, although no one can sing that note. Kevin McIlvoy, the author of the story collection 57 Octaves Below Middle C, is likewise, unique: I know of no one else who can sing his stories. They are always unexpected. It’s true that in recent years various authors have tried to find ways to write outside the box, but many fail in this endeavor. The human mind still longs to be logical and hopes for a reasonable, preferably favorable, reading. McIlvoy is the exception, his stories even stranger than those of Ben Marcus or Lydia Davis. So strange, sometimes, that it is difficult to put the story down. You may find yourself reading it over and over in search of meaning.

I have always thought that meaning is crucial. Sometimes it may be too plain for our taste, sometimes too clearly exhausted. But then, we open a backdoor and find a writer like McIIvoy, which means we are now in a crazy place without a clear idea of what’s going on. Knowing that, it is possible to simply follow along from sentence to sentence without questioning where we are or where we are going. For example, his story “Black sweater” (note to reader: cited text from here on out reflects author’s capitalization style) begins: “At the right time in his life, she visited.” A clear and crisp sentence. The woman commends him on his place. An apartment? A house? We don’t know. The man looks at her sweater and somehow finds it incomprehensible.

It was as if he’d never before seen a woman’s sweater arms not covering her slight wrists, not ending at her elbows either but where, according to some fashion rule, the sweater-arms must end: at her mid-forearms, which made him wish she might take it off and become for that one visit not incomprehensible.

These sentences remind me of a novel I read some years ago. The novel noted every detail of which the main character was aware. The author wrote as if he was certain the reader would be interested in every detail, or, more likely, as if the reader would be enamored of the writing itself. Fortunately for McIlvoy, he is writing short stories, which readers often welcome because of their brevity. “Black sweater” is under two pages. We need not feel we have wasted a day or a week. Furthermore, the very fact of brevity encourages readers to relax and take a moment or two to consider what the author may have been thinking about his story while he was writing it. As for the man who is watching the woman, he thinks about the possibility of the sweater falling off her shoulders or otherwise baring her arms, daydreaming for a moment that he might put his arms around her where her sweater was.

Other stories include “I was watching the movie, edited” and “Veterans day.” Some take on a longer length. One of my favorites is “Mrs. Wiggins’ altocumulus undulatus asperatus.” Is this Latin or pretend Latin, like Pig Latin? Perhaps it does not matter. Mrs. Wiggins writes to personages named Abraham and Kudzu. “Whenever I’m not the people in my dreams,” she says, “I start to think you’re the people in my dreams.” She says this without capitals or punctuation. What is even stranger is that as she continues to talk, the talk becomes ever battier. That is to say that perhaps she is a batty old woman. Turn the page and you will find her speaking on the subject of Tina Turner. Also, The Boss. But now she turns out to be a woman someone saw on television. Who is the speaker? Maybe McIlroy? In any case, what happens now is that the story unwinds. Maybe this is a comment about deconstruction, that fad of a generation, but if so, McIlroy is making fun of it. The paragraphs continue to dwindle until a photo of Mrs. Wiggins is mentioned (but not shown). It is possible that Mrs. Wiggins herself has been deconstructed, though it is also possible that Mrs. Wiggins was never more than a slip of the pen. Or the concerted effort of a pen and a writer.

McIlvoy’s story, “Notes on his poems by a guy who observed them in their natural habitat” is one of my favorite pieces, and it is a one-pager. “His poems slept where they ate.” Slept where they ate! I think this a brilliant line. “They were low on the food chain, these poems, the favored snack of predacious poems.” That’s another brilliant line. There are many in this book.

“Batter” is a story with a beautiful description of how a batter feels when he comes to bat. “He knows it never hurts to practice-swing, to pound the plate, to chop from the chin, from the gut, from the hip, to imagine the crack-sound, to knock the thing against his thighs, rap it against his lifted cleats, hold it up as if to switch on the ballfield lights with it.” I am not a baseball fan. I played softball in junior high but that was the beginning and the end of it. Yet, this portrait of a batter actually felt real to me, as if the batter were hitting balls on my lawn. That’s what really good writing does: it makes us feel that we are living in it. That we are the batter. That the guy who paid attention to his not-very-good poems may be a real guy. That Mrs. Wiggins and her two real or unreal friends are unraveling. That a man dreams of putting his arms around a woman in a black sweater.

These stories could be read in an hour, but to understand them, the reader should stop after each one, for the express purpose of thinking. Or rather, dreaming, for they are rather like dreams, these curiously tilted, somewhat wacky, often startling small stories. I recommend them to anyone who wants to visit new worlds.

About the Reviewer

Kelly Cherry is author, most recently, of Quartet for J. Robert Oppenheimer (poetry).