Recent years have seen an increasing interest in erasure poetry, in which a poet creates a new text by selectively erasing from another author’s pre-existing text. Poets Kristina Marie Darling and Sam Taylor are both practitioners of “self-erasure,” in which they first write their own text and then erase part of it. Taylor and Darling both developed self-erasure independently around the same time and then happened to be given studios next to each other at Yaddo, where they discovered the coincidence. They’ve been having a conversation about it ever since, and they’ve shared some of it here. For all the surging interest in erasures, there has been little discussion of the unique poetics and possibilities of erasure poetry. This conversation—between poets who explore erasure within their own texts—strives to expand the discourse on the poetics and ethics of erasure, as well as to illuminate the unique possibilities of self-erasure.

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of over twenty books of poetry. Her awards include two Yaddo residencies, a Hawthornden Castle Fellowship, and a Visiting Artist Fellowship from the American Academy in Rome, as well as grants from the Whiting Foundation and Harvard University’s Kittredge Fund. Her poems and essays appear in the Gettysburg Review, New American Writing, the Mid-American Review, the Iowa Review, the Columbia Poetry Review, Verse Daily, and elsewhere. She is currently working toward both a Ph.D. in literature at SUNY–Buffalo and an MFA in poetry at New York University. Visit her online at kristinamariedarling.com.

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of over twenty books of poetry. Her awards include two Yaddo residencies, a Hawthornden Castle Fellowship, and a Visiting Artist Fellowship from the American Academy in Rome, as well as grants from the Whiting Foundation and Harvard University’s Kittredge Fund. Her poems and essays appear in the Gettysburg Review, New American Writing, the Mid-American Review, the Iowa Review, the Columbia Poetry Review, Verse Daily, and elsewhere. She is currently working toward both a Ph.D. in literature at SUNY–Buffalo and an MFA in poetry at New York University. Visit her online at kristinamariedarling.com.

Sam Taylor is the author of two books of poems, Nude Descending an Empire (Pitt Poetry Series) and Body of the World (Ausable/Copper Canyon). He is completing a third collection, “The Book of Fools: An Essay in Memoir and Verse,” an experimental book-length poem that invents new formal structures to marry global, ecological themes of loss—focused around the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—to personal, confessional ones. Excerpts from this new manuscript have been published in the Kenyon Review, the New Republic, OmniVerse, and Tupelo Quarterly. The recipient of the 2014–15 Amy Lowell Poetry Traveling Scholarship and other awards, he is an assistant professor in creative writing in the MFA program at Wichita State University. His website is www.samtaylor.us.

Sam Taylor is the author of two books of poems, Nude Descending an Empire (Pitt Poetry Series) and Body of the World (Ausable/Copper Canyon). He is completing a third collection, “The Book of Fools: An Essay in Memoir and Verse,” an experimental book-length poem that invents new formal structures to marry global, ecological themes of loss—focused around the Great Pacific Garbage Patch—to personal, confessional ones. Excerpts from this new manuscript have been published in the Kenyon Review, the New Republic, OmniVerse, and Tupelo Quarterly. The recipient of the 2014–15 Amy Lowell Poetry Traveling Scholarship and other awards, he is an assistant professor in creative writing in the MFA program at Wichita State University. His website is www.samtaylor.us.

* * *

ST: You and I have this remarkable history. We met at Yaddo in 2011, where we had studios right next to each other, and we were both working on self-erasure poems next door to each other without realizing it. At the time, I thought I was the only person doing self-erasure and was reticent about talking about it, both because I considered it an infringeable concept and because it seemed like most people viewed it as a freakish project. Somehow you and I eventually got talking about what we were working on, though, and it was so marvelously strange to discover the universe had brought us into such proximity. So, I’m curious: How did you first come to the concept of self-erasure? What motivated that decision or invention? And, while we’re at it, let’s establish once and for all who first thought of this thing! I say this tongue-in-cheek since it seems clear such conceptual developments emerge from a synchronous collective mind, but when did you first arrive at the concept?

KMD: The story of how I discovered self-erasure begins like many of my stories. I met a guy who turned out to be truly awful, and by “awful,” I mean just terrible. It all started when he sent me a random email, saying that he liked my “poetry reading voice.” We started emailing back and forth, and eventually, we met. So I started to like him a little too much. Then, in what I interpreted as a gesture of complete love and trust, he asked me to erase one of his poems. So I erased it into a love lyric and sent it to him. This made things very awkward between us, I think, because he never spoke to me again. After that, I came to understand that I’m not very good at reading signs from men. But what had happened also sparked my interest in erasure.

Since I couldn’t erase his poems anymore, I erased my own. This was back in 2011. I became very interested in erasure as a way of expressing grief. Julia Kristeva writes in Black Sun that true melancholia, true mourning, represents a loss not only of a beloved object, but a loss of language. Words lose their meaning, and so too, grammar becomes insufficient for constructing relationships between phenomena. For me, erasure came to represent this kind of despair, a rejection of language and one’s own voice as being insufficient. Jeffrey Pethybridge’s Striven, The Bright Treatise is a great example of this kind of beautifully melancholic erasure. He includes pages in the book that are completely blacked out, referring to them as “mourning pages.”

As I continued to write and dismantle my own work, I started to think about erasure in a more expansive way. Your work, and the conversations we had at Yaddo, definitely helped expand my sense of what is possible within the realm of erasure. It is strange and wondrous that your work allowed me to see erasure not as entirely destructive, but as an opportunity for conversation and collaboration.

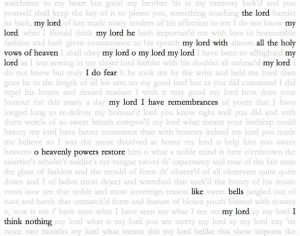

I’ve enjoyed reading drafts of your third manuscript, “The Book of Fools: An Essay in Memoir and Verse.” Your use of erasure in this project is especially innovative. It’s almost reminiscent of Jen Bervin’s Nets, with some words in black and others in grayscale. The erasure is literally haunted by the source text, which remains omnipresent even as words are excised and struck through. But it’s vastly different from Bervin’s work in that you’re erasing your own poems. How did this project begin? What sparked your interest in self-erasure?

ST: My memories are usually filed by place, and I remember the exact moment. I was walking over the bridge at the Vermont Studio Center in October of 2010. I had been so impressed by the conceptual innovations in the work of several visual artists there, and I wanted to find ways to make literary work as conceptually interesting. At that moment, as I crossed the Gihon River, the idea struck me. As you know, “The Book of Fools” explores loss at levels of memory and death, as well as ecological loss and destruction, and when I came upon the idea of erasure, it really propelled the book forward as a way to enact loss and haunting. I relate to your perspective of self-erasure as a vehicle for grief, but, as you suggest, I have also found the relationships between the two texts establishes an exciting interplay.

At the time, I had written a one-page poem that I found successful as a classical lyric, but I felt dissatisfied with its easy statement and closure. The form that made it successful as a lyric seemed to guarantee that it could not contain the complexity or emotional truth of the experience. I had already been complicating it, adding different takes and such, and then I had the idea to do a self-erasure. The erasure undermined the authority of the text and accessed something rawer and more chaotic. And while I say it undermined it, it also restored and revivified it by placing it within a spectrum of other linguistic potentialities and creating an electric tension among them. I see now the image of an anatomy textbook with overlapping transparencies of the body. Self-erasure adds a new dimension to a text, the dimension of a text’s relationship with all other possible texts that could have emerged from the same psychological or aesthetic moment.

Since you mentioned Jen Bervin’s Nets, I am wondering if I ever mentioned it to you, because it was, once upon a time, the first erasure I read, and I still consider it to be the gold standard of erasures. It seems definitive, not only because the poems are so moving in themselves, but because nothing could execute the concept better than netting such spare, fractured, alternative poems from a work as monumental, canonized, and seamless as Shakespeare’s sonnets. But, by now, while I find the concept of “traditional” erasures to be marvelous, I think it has been done in enough iterations that they offer diminishing returns; I can even find them tiresome unless they are motivated by some significantly new concept. In addition, at some point, they become frustrating in that the authors are not exactly writing anything. So, another reason I started exploring self-erasure was to innovate the concept—to restore conceptual freshness by marrying it back to authorship, while also introducing new possibilities.

I use Bervin’s typographical presentation partly as homage, but mostly because I am fascinated by the simultaneous presence of two texts, the relationship between them, and the undermining of any definitive text. I love how it reveals how any written text emerges from a larger mind-body sea of available text, imagery, rhythms, and sounds. A poet can consciously tune into and navigate this subconscious sea in different ways, choosing what to erase and what to highlight. So, for me, erasure is partly an exposure of process and a reflection on aesthetic choice, and often it allows me to develop a lyric narrative and a distilled pure lyric simultaneously. I love how it allows any number of relationships between the two texts: One can distill and intensify the other, can bend or twist it, can undermine it, can offer a counterpoint, or can do something completely independent. For me, self-erasure is also, perhaps ironically, an indictment of aesthetic ideology, whether from the mainstream or the self-styled avant-garde. I believe strongly in the full palette of aesthetic options and in the foolishness of declaring any style to be the right way or of limiting oneself before one even begins. That’s one of many reasons the manuscript is called “The Book of Fools.”

Now, while I’ve been focused entirely on one book of erasures these past five years, you’ve completed a series of them, and you’ve done erasures of both your own work and the work of others. I am curious whether you see yourself making different discoveries with each erasure project, and I wonder if you could talk about the evolution of your erasures from book to book. Also, in what ways is your experience in erasing your self different than your experience in erasing the work of others, such as in your erasure projects with Lolita and Hamlet?

KMD: For me, all of writing, whether it’s erasure of one’s own poetry, erasure of someone else’s work, or a conventional single author poem, is a collaborative act. Self-erasure, then, becomes a dialogue, a conversation between parts of the self or parts of consciousness. It may be that these facets of the same person existed at different temporal moments, such as during and after the writing process, or before and after trauma. Or perhaps these two parts of this same individual continue to coexist. What’s interest about self-erasure is that it forces these parts of the self to confront one another. Perhaps this is why I loved your description of poetry as an attempt to navigate the ocean of the subconscious. Self-erasure becomes a visible attempt to excavate from, and respond to, what has been buried in one’s own consciousness.

In this respect, self-erasure is vastly different from erasing someone else’s work. So much of the time, an erasure of a canonical figure like Vladimir Nabokov becomes a mere critique. In this particular erasure project, started in late 2013, I excised text from Lolita in order to recast the narrative from Lo’s perspective. There’s nothing wrong with this, but it’s very different from self-erasure, since the dialogue that happens is with something external to the writer’s consciousness. There are many erasures that critique the source text, which I find fascinating: Yedda Morrison’s Darkness, Ronald Johnson’s Radi Os, Jen Bervin’s Nets, and so on. But the work that they do is very different from that of self-erasure.

In this respect, self-erasure is vastly different from erasing someone else’s work. So much of the time, an erasure of a canonical figure like Vladimir Nabokov becomes a mere critique. In this particular erasure project, started in late 2013, I excised text from Lolita in order to recast the narrative from Lo’s perspective. There’s nothing wrong with this, but it’s very different from self-erasure, since the dialogue that happens is with something external to the writer’s consciousness. There are many erasures that critique the source text, which I find fascinating: Yedda Morrison’s Darkness, Ronald Johnson’s Radi Os, Jen Bervin’s Nets, and so on. But the work that they do is very different from that of self-erasure.

There are also many erasure poems that strive to excavate material from the source text, which may have been overlooked. Erasure becomes a way of redirecting the focus of scholarly or critical attention, a way of forcing us to confront something in the source text that we may have avoided. A good example of this would be Janet Holmes’s brilliant book The Ms of My Kin, an engagement with Emily Dickinson’s work that excavates her most politically charged material. Again, the work of this kind of erasure is simply very different from self-erasure, as the conversation that takes place in books like Holmes’s is external to the individual. What’s different about self-erasure is that it externalizes something that is purely internal, this interaction between facets of the same consciousness. Not only that, but it makes possible an exchange between parts of the self, which often exist as distant ships traveling along the same coast.

With that in mind, I’d love to hear your thoughts about the relationship between self-erasure and the lyric. Your previous books, Body of the World and Nude Descending an Empire, offer beautiful lyric poems in a more traditional sense. How do the terms of lyric address change when you engage in self-erasure? How do changes to the visual appearance of the poems (such as grayscale, strikethrough, and footnotes) serve to problematize, comment on, and expand what is possible within our understanding of lyric address?

ST: First, I love what you say about the difference between conversation with another and with oneself, and it reminds me of what Yeats said about poetry coming from the quarrel with oneself. But, to answer your question, even in “Fools,” I was usually—though not always—first composing a traditional lyric and then in the erasure problematizing, distilling, or enriching it. I think, however, that the extent to which I was engaged in this quest and the extent to which I did not consider any text definitive led me toward greater freedom and experimentation in the original composition.

I think poetry is always partly a navigation between the said and the unsaid, but traditional lyrics make a definitive version that sculpts immemorially the line between what is said and what is not said. Erasures, strikethroughs, and footnotes all create a third category or multiple categories in between what is said and what is not said, and they score a more complicated movement between said and unsaid. Look at all the categories: What has been said but erased. What has been said but erased but is still there in a ghostly way. What is hidden inside what is said, but has not been said, or would not have been said if an erasure had not been done (and in this sense, an erasure can also be viewed as an archaeological rescue). What has been doubly said (said in a full text that remains and said in a highlighted erasure text). And with strikethroughs, the presence of something crossed out is not the same as those lines not being there at all, and it’s not the same as those lines being ghosted into a faded erasure. They are there along with the decision not to include them, and the reasons for including certain lines and not others becomes part of what the poem is about. And sometimes there are things that can only be said that way. I had one piece in the manuscript to which I had never done any post-production scruffing, and I always felt strongly ambivalent about the piece. Just recently, I crossed out two-thirds of the poem, and it now feels right to me. But, it would not work at all if I had simply cut those lines; those lines have to be part of the poem, but as a kind of negative version of themselves, dark matter. So, there is what you say you say and what you say you do not say, though there still remains what you do not say you do not say.

Our experience is less singular, less enduring, more fragmentary, more conflicted, more simultaneous and layered, and less marked by closure than a traditional lyric poem. Nevertheless, through this process, I have come to the conclusion that a traditional lyric poem’s structural unity feels true in the way that myth feels true. The more I questioned the lyric and gave license to these other dimensions, the more I came to appreciate the lyric for what it was, a mythical structure with access to our spirit.

I want to return to what you were saying about erasure being a conversation or critique and ask a question from another angle. Erasure has sometimes been considered a form of Conceptual Poetry. In “traditional erasure” the author both does and does not create a text, instead transforming a prior text, so it has been seen as being aligned with writing that was “against expression.” As we all know, last year was a disastrous year for the biggest self-promoters of Conceptual Poetry, as Kenneth Goldsmith and Vanessa Place received widespread criticism for projects and performances that many considered racist, or at least insensitive appropriations. Obviously when you and I engage in self-erasure, our conceptual emphasis is “for expression” and there are no ethical questions in using our own work or making decisions of what to say and what to silence. But I am curious what ethical considerations or responsibilities you think might lurk in erasing other people’s work. Your erasures of Shakespeare’s plays and Nabokov’s Lolita seem beyond reproach in that they are engaging with canonical, white male works in a conversation transparently framed as respectful criticism. To me, they seem equivalent to critical essays, except that they use a more creative form. But what if the relationship is less respectful, or if the work in question is not old and canonical but contemporary, or if the work involves a different balance of power?

I want to return to what you were saying about erasure being a conversation or critique and ask a question from another angle. Erasure has sometimes been considered a form of Conceptual Poetry. In “traditional erasure” the author both does and does not create a text, instead transforming a prior text, so it has been seen as being aligned with writing that was “against expression.” As we all know, last year was a disastrous year for the biggest self-promoters of Conceptual Poetry, as Kenneth Goldsmith and Vanessa Place received widespread criticism for projects and performances that many considered racist, or at least insensitive appropriations. Obviously when you and I engage in self-erasure, our conceptual emphasis is “for expression” and there are no ethical questions in using our own work or making decisions of what to say and what to silence. But I am curious what ethical considerations or responsibilities you think might lurk in erasing other people’s work. Your erasures of Shakespeare’s plays and Nabokov’s Lolita seem beyond reproach in that they are engaging with canonical, white male works in a conversation transparently framed as respectful criticism. To me, they seem equivalent to critical essays, except that they use a more creative form. But what if the relationship is less respectful, or if the work in question is not old and canonical but contemporary, or if the work involves a different balance of power?

KMD: That’s a great question, and one that I can only begin to answer. Yes, it becomes quite dangerous to erase a text that already embodies some imbalance of power. This privilege can be conceived of in terms of race, gender, sexual orientation, class, ethnicity, age, professional status, or any combination of these things. With that in mind, recent years have seen a number of grave lapses in judgment, especially when choosing source texts for erasure projects. In one rather extreme example, I found myself cautioning a female colleague against doing an erasure of Anne Frank’s diary. For me, this example shows one very disconcerting trend in contemporary literature: writers become so enraptured by “the concept” that they forget themselves, their own place in the literary landscape, and their privilege. The insular nature of academic communities fosters such privilege-blindness as it places us again and again alongside people who share our same backgrounds and experiences.

This privilege-blindness is often the beginning of the disasters you describe in so much of conceptual writing. I say this because erasure is perceived first and foremost as an act of violence, whether the intention is to excavate, reframe, or unearth text, there is a destructive quality inherent in this kind of artistic gesture. To see textual violence done by someone already in a position of privilege is what’s perhaps most egregious, as it serves only to maintain what is already an uneven playing field. It is also possible to initiate dialogue about systemic injustices, but this requires that we become aware of our own complicity, and fully acknowledge it. And this is where the projects you describe fall short for me. The responsibility is not so much to choose a source text by someone in power, but to understand and acknowledge one’s complicity within a broken system.

This is exactly what “The Book of Fools” does so well. Although some of your work engages contemporary constructions of masculinity, this new collection negotiates such privilege with vulnerability. The speaker not only shows a keen awareness that his voice emerges from a position of power and authority, but he also deconstructs and dismantles that same voice. Which leads me to my next question. I’m curious how this awareness of the multiplicity housed within each voice, each page, and each text has changed your practice, particularly when working in forms other than erasure. You have mentioned in the past that you might not do another erasure project, but is it possible to return unchanged to the lyric after one engages in erasure? How has your relationship to voice, its inherent subjectivity, and its place in time metamorphosed as a result of these experiments with form and technique?

ST: I think your statement on the dangers of erasing a text that already embodies some imbalance of power is excellent, and I hope it gets quoted often! I was having a dialogue last year with the Vietnamese-American poet Hoa Nguyen when she learned of a white male poet who did blacked-out erasures of some of her poems. She seemed to feel offended but also to be struggling to understand the gesture, as she talked with the “eraser” and eventually concluded she could not. When I looked at what he had done, I was struck by how the erasure did not seem to have any relationship with her original text, other than perhaps a dismissive one. She had written a poem on the corrupt prison system, and he had turned it into “find fun,” which didn’t seem to represent either a respectful or a legitimately critical dialogue. Combine that with the historicity of the subject positions involved and it becomes even more disturbing. I think your emphasis on erasure as conversation asks that a practitioner be aware of whom one is talking to and the position from which one speaks, not to mention attentive to the text. And, you are probably right that violence will usually be a default understanding of erasure, so that the burden is on the practitioner to establish a dialogue that honors the integrity of the original or is transparent in its critique. In the example mentioned above, the individual was doing hundreds of these black-outs of other writers, and they seemed to me to be rather careless texts, in dialogue with nothing, neither self nor other, truly against expression. And I suppose that points back to the larger critique of writing that is “against expression”: such writing often seeks to nullify the power of language without acknowledging that language has already been used to create material structures with massive imbalances of power, what you call above “the broken system.”

As far as your question about how my practice of self-erasure has changed my relationship to voice, subjectivity, and time, as I suggested earlier it has actually made me more comfortable with the lyric as a myth and an aesthetic object. In “Fools,” I was pursuing some kind of truthful way of representing the actual, some nonfiction; and I couldn’t find it. Or, perhaps, I could find it only at an emotional level, and I’m not even sure about that. So, ironically, working with erasure has made me more comfortable with the classical lyric, accompanied by a clear-eyed acknowledgment that the lyric is a myth, because I don’t think there is a definitive reality waiting to be found by another route either. This might be analogous to appreciating religious myths once one has clearly removed them from any claim upon fact. It is funny to say this in an age so relentlessly driven by “reality hunger,” but I’d caution that we shouldn’t confuse the legitimate hunger for the texture of reality with trying to isolate, concretize, and possess a certainty about what really happened. Keats might call the latter hunger “an irritable reaching after fact.”

I think I will probably work with a more complex relationship between what is said and unsaid some time again, perhaps especially with strikethroughs. Such modes are equivalent to playing three-dimensional chess. Yet, I also have a further appreciation of the two-dimensional game, and I know I have more to say and learn in that realm. For now, I’ll let Shakespeare and Dante duke it out on that other astral plane. I also think erasure works particularly well for a very inward kind of lyric, and I am starting to work on a new book whose themes are more public and more given to a regular lyric. I am beginning a book of poems tentatively titled “The Miseducation of Samuel Beckett,” whose themes include race, identity, and the Jewish diaspora. What are you working on now? And how does it grow out of or relate to these other erasure projects that you’ve done?

KMD: Great title! I look forward to your new collection. And thanks for asking about my current projects. I’m working on a new poetry collection, “Dark Horse,” that engages themes of marital infidelity and the way that our culture fosters competition among women, rather than encouraging community. For me, this in itself is a form of erasure, a dismantling of possibility, dialogue, and identity. Which is to say: I couldn’t write the book without erasure. The collection begins and ends with the plain black “mourning pages” that I alluded to before. The mourning pages comprise a preface and an afterword, suggesting that the narrative we are presented with arises out of this melancholia, this loss, and returns again to it.

With that in mind, I think what you said about nonfiction, the impossibility of factually representing an experience with some degree of emotional truth is especially perceptive. For me, the difficulty of negating facts with what feels true is what makes me turn to fiction, to use metaphor as a way of rendering what is essentially an internal drama. “Dark Horse” arises out of the events of the past year or so of my life, but it is mostly fiction, as this narrative arc seemed the only way to accurately represent what is a purely interior drama occurring over a fairly long duration of time. Much like you, I take issue with the tendency to equate metaphor with fiction, as I think it is often the most concise way to tell the truth. And as we see in your recent work, metaphor, more often than not, encompasses form in additional to content.

Much like “The Book of Fools,” “Dark Horse” is essentially an extended metaphor, constructed through form as well as narrative, for what was my inner experience for a fairly substantial period in my life. That’s why I think your allusion to games, chess, etc. was so apt. We are constantly trying to anticipate readerly habits, manipulate them, and elicit empathy for the experiences that we are rendering. In this sense, the reader is a kind of opponent, whom we try to outmaneuver through formal innovation, narrative ruptures, and other surprises, in end bringing them back to a place of understanding, even compassion. There is nothing at stake in this game, but at the same time, everything is at stake. We erase a bit too much and someone else inherits the world.

ST: That certainly sounds like an interesting project, Kristina. As you suggest, so much of the world is an erasure, a messy palimpsest of strikethroughs, blackouts, whiteouts, erasures, and write-overs. It makes sense that certain subjects demand highlighting this rippling plasticity, with both its violence and forgetting and its discoveries. Much as I agree with most of what you’ve said, I have to add that I don’t see the reader as an opponent. Navigating layered relationships of said and unsaid creates a more complex sport of consciousness, but it remains one in which I feel deeply allied with the reader. I feel as though we together face the same challenge, like an outward bound event in which success depends on each other. I must think of the reader, and the reader must think of me, if we are to avoid falling off the high wire that spans the void (the unsayable on one side, the already trite on the other). That is, if we may still presume any reader beside us at all—which reminds me, returning to your theme of conversation, what a privilege it is to have someone to talk to in these realms. Thank you for the conversation!