Book Review

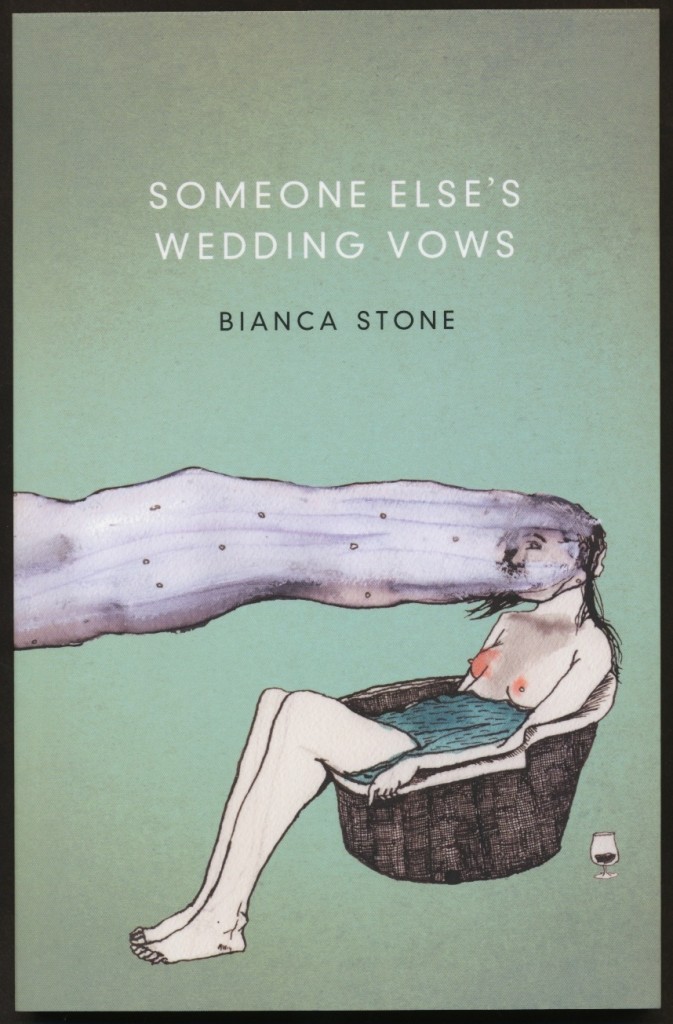

Do you remember learning about bimetallic strips in middle school? The expansion rate of one metal was different from the expansion rate of the other, which made them perfect for thermostats because the temperature of the room would cause the coil of bimetallic metal to unwind or retighten, turning off or on the heater in the room. That is what it feels like to read Bianca Stone’s Someone Else’s Wedding Vows—where Stone is one metal, and me reading Stone is the other metal. Her experience of the world occurs at a different rate than mine. And so when things heat up, and by things I mean grief, or the trivialities of life, or getting a Frappuccino at Starbucks, or maybe shaving your legs, there is Stone experiencing life on a different register than me. She is imagination exclamation-pointed. She is always thinking about an image that would do a much better job explaining what experiencing is like. And so Stone bends her reader to her will, or to her willful imagination, or just to how her imagination will all her life be explaining her experience to her.

Do you remember learning about bimetallic strips in middle school? The expansion rate of one metal was different from the expansion rate of the other, which made them perfect for thermostats because the temperature of the room would cause the coil of bimetallic metal to unwind or retighten, turning off or on the heater in the room. That is what it feels like to read Bianca Stone’s Someone Else’s Wedding Vows—where Stone is one metal, and me reading Stone is the other metal. Her experience of the world occurs at a different rate than mine. And so when things heat up, and by things I mean grief, or the trivialities of life, or getting a Frappuccino at Starbucks, or maybe shaving your legs, there is Stone experiencing life on a different register than me. She is imagination exclamation-pointed. She is always thinking about an image that would do a much better job explaining what experiencing is like. And so Stone bends her reader to her will, or to her willful imagination, or just to how her imagination will all her life be explaining her experience to her.

For example, in the poem “Elegy with a Darkness in My Palms,” Stone writes a poem for a fairly familiar occasion. It is Christmas Eve. She is at home and the poem has that special loneliness that we feel around our families during the winter holidays, like perhaps we should feel closer to them because we all share a mutual history. And yet there is a sense of lingering alienation. And yet, however familiar the circumstances, Stone’s imagination renews it. There is “the size of darkness in my palms / that shake out like emerald hummingbirds.” There is throwing a rind of toast at the moon “that recedes into the clouds like an iridescent testicle / into the holy lap of the atmosphere.” There is the apartment in Brooklyn that is an empty submarine. Is this what life is when this speaker is living it? A world emphasized by imaginative potential and explanation. An exaggerated world. A world on the verge of detonation.

And what chaos it is. In the world of Stone’s imagery, chaos is everywhere. It is in the speaker’s psychology. It is woven into the landscape. And often it is in both at the same time. It could be chaotic circumstance that prompts the psychology to a vision of order. It could be a chaotic psychology being placated by the habits that order human life. “I cannot love like a ninepin. Not / like the lane. Not like the blue shoe” says Stone in “What It’s Like.” If using the terms of chaotic circumstance the speaker could be personifying the different parts of bowling, so she can compare them to her personal, steadfast love. In terms of a chaotic psychology, we could be hearing from a speaker unable to describe the emotion inside her; the poem becomes her search among the ordered world for a suitable analogy.

It is perhaps ironic that this gesture towards chaos is often the most controlled part of the poem. While the poems manipulate chaotic circumstances, live off the chaotic impulse, and situate chaos as a hallmark of the human condition, all the images and circumstance make such an orderly appearance in the poems. The occasion and the setting are usually the most fixed elements. The poem “What It’s like” is a good example. The “I cannot love…” statement quoted above is followed by an “I can love…” statement, which is followed by two “This is….” statements:

This

is a pond where thousands

of black tadpoles loiter at the rocks.

This is a wooden raft being tipped

by an assembly of teenagers.

The imagery here is both fresh and unusual, yet it doesn’t push the poem out of its regular structure and order.

I like thinking about how poems that operate like this could be called a wedding vow, even if that vow is someone else’s. Wedding vows touch on all the chaos that might come to life, like sickness and health and grief and wild successes and horrible defeats, yet they also try to tell the beloved that all the normal, inconsequential things that happen in life are just so much better when that person’s around. Life will likely be unpredictable, says the wedding vow, but we can vow to let this new person bring some sensibility to life—even bring unpredictability to life. Granted, these poems aren’t much of an avowal. They are not really promising anything to anyone. These are personal testaments about normal life, normal devotion, as seen by an imagination that could explode what we expect in any normal moment. What is your human life like? Stone’s poems go there. But then the poems color that life different. Stone’s poems bring the quotidian into bloom.

These blooms aren’t only in adoration and light. There can be a darker side to the vow. Part of your promise involves what you fear most you might forget. In Stone’s words:

Devotion is like

an MCG 8 museum climate control machine

calculating temperature

in the corner of the room

or a continuous subsonic boom

confined to my skull

What are you supposed to do if your undying devotion drowns out what you’re supposed to feel when you’re devoted? Put more plainly, how do you keep from slipping into an automatic devotion? All devotion has a dark side. It must. It’s a part of our human lives. And the fact that Stone’s poems include this darker element should only underscore the reality of her devotion. “Our love is so meager / I have to hold it in my hands / like a white moth” she claims in another section of this poem, “Monsieur.” For lesser loves, this might be a concern. But big love, the kind of love continually appearing in Stone’s Someone Else’s Wedding Vows, is the kind of love that will be lived with for years, that will be analyzed and exploded and breathlessly evaded only to be breathlessly clutched at too tightly. How is the imagination not the natural part of a process like this?

About the Reviewer

Kent Shaw’s first book, Calenture, was published in 2008. Poems have since appeared in The Believer, Ploughshares, Boston Review and elsewhere. He is Poetry Editor at Better Magazine and an Assistant Professor at West Virginia State University.