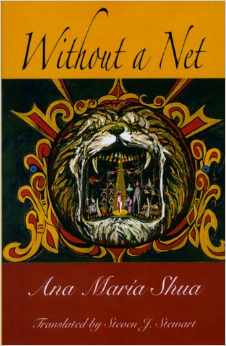

Book Review

Trapeze artists and animals. Freaks and clowns. Crowds, high-wires and swallowed swords. In the same way listeners raised on digital music still recognize a scratched-record sound in a radio ad, the images in Ana Maria Shua’s Without a Net evoke a circus whether or not we have been to one. The book’s 99 microfictions, divided into a prologue and five sections, use tropes of circus life as metaphors for life beyond the big top, even as they challenge the argument that there is any clear distinction. At the same time, Shua subverts our common expectations of a circus, and defamiliarizes a world we think we know. Like fellow Argentinians Borges and Cortázar, her abbreviated fictions often serve as games in which the chief rule of participation is multiple re-readings.

Trapeze artists and animals. Freaks and clowns. Crowds, high-wires and swallowed swords. In the same way listeners raised on digital music still recognize a scratched-record sound in a radio ad, the images in Ana Maria Shua’s Without a Net evoke a circus whether or not we have been to one. The book’s 99 microfictions, divided into a prologue and five sections, use tropes of circus life as metaphors for life beyond the big top, even as they challenge the argument that there is any clear distinction. At the same time, Shua subverts our common expectations of a circus, and defamiliarizes a world we think we know. Like fellow Argentinians Borges and Cortázar, her abbreviated fictions often serve as games in which the chief rule of participation is multiple re-readings.

The title of the book’s first section, It’s All a Circus, opens a metaphorical umbrella over the fictions beneath it. The stories that follow introduce us to new circuses—“Dubious Circus,” “The Ghost Circus,” “My Dream Circus,” “The Poor Circus,” and “The Poorest Circus,” which reads:

“The Papelito circus still goes through small towns all over Argentina, modest and picturesque. Its first big top was made from burlap bags and the spectators had to bring their own seats.”

“But there was another circus that was even poorer. Besides bringing their own seats, the spectators had to sit down and pretend they were watching the ring, to imagine it.”

The story glides from a concrete image to a circus that exists in abstraction, and yet that abstraction is treated by the audience as concrete. The story’s circularity invites readers to a challenge of reification even greater than that of the audience within the story; while they imagine the circus, we imagine the imagined circus. A story like this becomes a hall of mirrors we are reluctant to leave. The first section also contains the existential story “Why?” in which animals continue performing after their trainer disappears, and “The Math Class,” one of the book’s many stories that argues for no clear line between circus and life. As we read on, the microfictional form invites us to view the circus as a figure with infinite sides, through brief bursts of story that suggest the whole without articulating it.

In the sections that follow—The Performers, Freaks, The Animals, and Circus History—Shua riffs on circus life as we imagine it to be, creating an audience as a circus of its own, rewriting mythology as a circus, and taking speculative flights to other planets and future eras. Narrators speak with absolute authority, informing us of events hundreds of years apart, and we frequently encounter the pleasant conundrums to which the microfictional form lends itself. For example, “The Great Garabagne:”

“Magic has its limits. Not even the boldest magician dares to promise to be able to grant every wish, not even every simple wish, of his audience members. But the great Garabagne promises, with a great display of artifice, the opposite. With his magic he can make it so that your wishes never come true. His fame around the world keeps growing as no one dares put it to the test.”

In a section called Freaks, one might expect deformity and horror, but instead a meditation on Diane Arbus opens it: “With morbid childlike curiosity and thrilling subtlety, the photographer Diane Arbus (1923-1971) chose to capture the tragic beauty of monsters.” The factual tone rebuts sensationalism, while its adjective-heavy clauses project a contained excitement. This tension of legitimacy versus prurience is extended in a subsequent line: “She became an artist in the same field that Barnum grew as a promoter.” Another fiction informs us that Barnum wanted his circus’s freaks to maintain “something of their human form, because only a deformation of the normal and familiar can provoke that effect of horror and fascination.” Again, the almost clinical diction suggests an internal struggle to desensationalize. The narrator of “It’s All Relative” is an extraterrestrial (Shua has no fear of the fantastic) relegated to freak status on earth, who laments that on her home planet she won beauty contests. Freaks is appropriately the shortest section in the book; this is a circus, after all, and freaks are a side show.

Animals in Ana Maria Shua’s circus might have two, four, or eight legs. Microbes and mythological creatures appear in the ring, lion tamers put their heads in big cats’ mouths while wearing helmets, and the lions’ union demands dental compensation. Animals are brutally beaten “to the audience’s pleasure and outrage” but prove to be human performers only disguised as animals. Elephants, however, are conspicuously absent—that there is no elephant in the room might be the elephant in the room. The menagerie throughout microfictions such as “The Fake Horse,” “Animal Rights,” and “The Liger” confronts the traditional centrality of animals in the circus as well as the complexities of cruelty-as-entertainment. If we go to the circus expecting animals and instead see ourselves, we should not be surprised.

Without a Net ends with a challenge to in-the-beginning expectations of linear time. The word circus means “circular line” in Latin, and in this collection of circus microfictions, the beginning comes at the end, and the end—“Circus History” deals with the beginning. Or does it? Circus time is fluid, apparently, and we encounter a past whose characters and images sprawl from antiquity to the future. As in the rest of the book, occasional lyricism here punctuates diction that is largely spare and direct to powerful effect.

Throughout her seductively phantasmagoric microfictions, Shua blurs the boundaries between audience and performer—and between character and reader—proving that while people may dream of running away to the circus, life once there is no dream.

About the Reviewer

Geoff Kronik lives in Brookline, MA. He has an MFA from Warren Wilson College, and his work has appeared in Salamander, The Boston Globe, SmokeLong Quarterly, Litro and elsewhere.