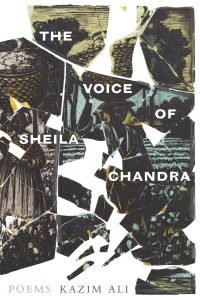

Book Review

A strange energy propels a Kazim Ali sentence. Heed me, it calls, and like one of the heads of the Cerberus, it bites, it snaps, and it rips one apart. The source of Ali’s power comes not merely from the spring of language, but from the tides of history. History has not been kind to those of us who are people of color and it is through the seven poems of The Voice of Sheila Chandra that Ali proposes to speak—not as one but as divergence, not through polyphony but through cacophony—to the set of struggles that unite people of completely different nationalities, races, and cultural backgrounds.

A strange energy propels a Kazim Ali sentence. Heed me, it calls, and like one of the heads of the Cerberus, it bites, it snaps, and it rips one apart. The source of Ali’s power comes not merely from the spring of language, but from the tides of history. History has not been kind to those of us who are people of color and it is through the seven poems of The Voice of Sheila Chandra that Ali proposes to speak—not as one but as divergence, not through polyphony but through cacophony—to the set of struggles that unite people of completely different nationalities, races, and cultural backgrounds.

The titular poem compels one to read it in a particular fashion. Originally, I have to confess, I did not know anything about Sheila Chandra. Only after I did a Google search did I learn there was a British singer of Indian origin who suddenly lost her ability to sing, speak, and laugh due to a strange illness called Burning Mouth Syndrome. What a strange thing, I thought, to be suddenly be rendered mute, particularly as an artist who derives one’s entire sense of self from the use of one’s voice. We as artists use our medium to get closer to that eternal wavelength that can be described as celestial. When I read about what happened to Chandra, it felt almost like an act of the gods striking down an artist for daring to come closer to their heavens.

If Chandra was cosmically punished for daring to act, Ali has come to resuscitate her voice and to strike the divine where it hurts.

Dark earth come Sheila

Dame ocean dome this poem

Roam to tome tomb foam

It is an incantation; it is a chant. The words are coming together as if to form an “Ohm” (ॐ). But unlike the eternal syllable, these words are not an invocation of peace. The “roam” and “tome” hit against the pallet like battle drums. They have all the urgency and sweat of a modern rap, while feeling lilted and melodic like epos. Ali staggers on. He blurs between reflections on Sheila Chandra—

Sheila Chandra sings without words

Because a word is a form of rage at

Death the implicit formlessness

Of the body

—with aching reflections on sexuality, relationships, and love—

In New York once I took a friend to a party he

kissed every man in the room including

The waitstaff the bartender and the program

Director of the foundation

The language never loses momentum, it never loses pace, as Ali strives to throw words out to the cosmos with the velocity of an electron. The words never lose poetry no matter how ugly they initially appear.

Ali’s poetry is clearly meant to be read aloud; the poem “Tagaq Sutra” trysts linguistically between English and French:

Pilgrim in parts

Ply the route entire entre

mensonge and mon songe

The play between “mensonge” (a lie) and “mon songe” (my dream), along with the alliteration between “pilgrim,” “parts,” and “ply” create a melody that can only be understood if read aloud. Similar alliteration occurs in the poem “Recite.” The lines “[crassness] of calling [a] body a corpse” create a harsh cacophony between “crassness,” “calling,” and “corpse” which can only be felt fully if thrust forth with the tongue.

Ali also has a keen gift of observation. In “Phosphorus,” part love ode to Berlin, part experiment on the limits of language, Ali opines of Berlin as:

a city you write yourself against

Unlike New York or Paris which write themselves into you

That the city itself has no voice or

If it has one it agrees to mute

Itself against the noise of your own life

Or is it a chorus of voices sedimented

A voice in which the present life is overlaid

On voices from history

An aural palimpsest

Ghost town with golden stumbling blocks in the street.

This is one of the most astute observations of Berlin I have seen in a poem, and as someone who has visited the city once or twice, it gave me explanation as to why Berlin never charmed me, but remains gripping to those who choose to make it a home.

The best poem of the collection—in my opinion—is also the one that takes up the most space: “Hesperine for David Berger.” Based on its innocent start, one would not expect it to be such a maelstrom of emotion:

Begin with the dining room attendant at the ivy-covered university who smashed the stained-glass window because we are now actually going to change history.

No word is particularly ornate, no word particularly stands out, and yet we have a sense of anticipation. Ali continues: “in the suburbs of Cleveland a sculpture of steel rings [breaks] in halves,” and “a painter [leaves their] canvas entirely and instead [looks] at all the extant surfaces in the already man-made and man-frayed world.”

I learned that the man Ali is referring to, Corey Menafee, was a waiter in the dining hall at Yale, and one day, he got livid, and broke a windowpane depicting slaves. But this is not only a poem about Corey Menafee. At the same time, “David Berger … [moves] across the world to Israel to train and compete in the Olympics, 1972 Munich” while Imran Qureshi “paints little blossoms on the ground on the wall in corners of the room.”

As Menafee fractures the glass, a kaleidoscope of narrative begins. With each sentence fragment, Ali crisscrosses into another human mind. The Greek God Hesperus “shines with a cold light through the tightest drawn evenings sharp-edged and dissolute.” In the next sentence, Ali writes of how Menafee “came into work in the dining room everyday and he hated that one image in the glass and one day he just.” The thought doesn’t continue, but instead blurs into Qureshi in Pakistan: “And of all that was wrong was a pattern painted not last year or a hundred / years ago but I mean yesterday or this morning.” The language continues on, blurring between Menafee, Qureshi, Berger, the singer Amjad Sabri, the physicist Stephon Alexander, various other narrators that are blipped through lines of the Qu’ran, and possibly, the rims of the universe itself.

Much like Cloud Atlas by David Mitchell, Ali creates a ripple through time and space, entering all the corners of our planet at times where people were wronged. The form gives Ali a chance to speak more directly to the universe than had he structured a novel. In slivers of language, Ali asks, “What if God is improvising like Coltrane?” or “Can history be unwoven the tightness released to make it possible to breathe and write anew?”

We will never be sure of the answer to these questions, but The Voice of Sheila Chandra ascertains that much like the shells against the ocean’s coast, Ali’s voice is firming and finessing with each year. He is coming closer to writing his masterpiece, and until then, The Voice of Sheila Chandra sings song to his talents, convictions, and depth of vision.

About the Reviewer

Kiran Bhat is a global citizen formed in a suburb of Atlanta, Georgia to parents from Southern Karnataka, India. An avid world traveler, polyglot, and digital nomad, he has currently traveled to over one hundred thirty countries, lived in eighteen different places, and speaks twelve languages. His homes are vast, but his heart and spirit always remain in Mumbai, somehow. He currently lives in Melbourne.