Book Review

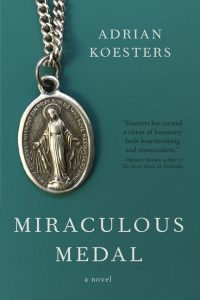

One need not read Union Square, the 2018 novel preceding Adrian Koesters’s Miraculous Medal, to enjoy her latest work. However, this slim, powerful volume presents a world so viscerally haunting, readers are likely to pick up both. In each, Koesters balances the music (and often the humor) of her characters’ voices with unflinching portrayals of sexual abuse, religion, stratifications of class and race, and the cultural reverberations of cyclical, endemic violence.

Adrian Koesters’s background in poetry permeates the prose of Miraculous Medal, her second with Loyola University’s Apprentice House Press. The current book begins where the last ended, entrenched in Baltimore, 1952, with one brief, powerful vignette. There, we find a priest, Father John Martin, wrestling with his attraction to a woman who has long tempted him. When he retreats, choosing a path of virtue, we’re left with an unsettling complication. A girl’s voice floats down from the woman’s row house window to embed itself in his conscience: “Ain’t you gonna come up? We could do somethin.” He debates. Should he ensure the child is safe and well cared for? Or should he take the path of least resistance and keep his vow of celibacy intact? With no small dose of gravity, he walks away, leaving the reader to wonder: What was the real fear that caused his inaction?

From that moment, we jump twelve years to 1964, and Father John Martin’s decision casts an unsettling shadow over the pages that follow. We rove through a cast of characters all deeply connected through a long dead but still much-loved neighborhood matriarch, Miss Maurice. Because of Miss Maurice, Father John Martin, a white Catholic of Jewish heritage, is the god-brother of Black parishioner Jezriel Maurice Heath, or Jeb, who, when not sweeping the church steps, is compelled each day to methodically walk the streets of his Union Square neighborhood. From the opening, Jeb’s tone is monastic and meditative as he considers the broom the priest gave him. Father John intimated the broom was as sacrosanct as the holy communion chalice. Another character might be touched or simply wave off such a comparison. Instead, we learn the depth of Jeb’s contemplation: “He did not know how the priest could bring himself to equate the actual consecration, where his own hands did not even touch the sacred metal of the chalice, and surely this was a disembodied action of which the priest had little if any part, to holding a broom.” In the end, though, Jeb permits “himself to agree that it might be so.”

And as we follow Jeb on his daily travels, we’re shown that it is, indeed, so. Through his encounters and observations of the day-to-day, we find mysticism in the mundane. Whether the people Jeb meets are menacing or welcoming, all carry an otherworldly, shimmering quality. Visions that might best be described as visitations are as commonplace in Jeb’s wanderings as more familiar sounds and sights. This day in the life leaves readers to ask where the division between the physical and metaphysical can be cleanly delineated.

That same question then threads through a day in the life of eight-year-old Marnie Signorelli, Father John Martin’s cousin. With a voice echoing such memorable protagonists as those crafted by George Saunders, Marnie’s zeal for Catholicism (as she naively understands it) is matched only by her voracious, if sinful, pride. Evoking hilarity and mortification alike, we learn of Marnie’s breathless excitement over earning three medals in a door-to-door church booster sale. She proclaims, “Nothing in this life had ever been seen, not Barbie dolls nor paper dolls nor roller skates nor crown jewels, as perfect and beautiful and everlastingly fine as those medals.” The titular medals, worldly and coveted as they are, are deemed “miraculous” by Marnie—she is certain they will protect and uplift not only herself but also her shy best friend, Alice Smaling. We quickly learn both characters could, indeed, use some divine protection. A vicious bout with chicken pox has left Marnie with a life-threatening heart condition, while next door, Alice’s recently-divorced mother’s latest beau, boxer Paddy Dolan, has made Alice his sexual prey.

How Koesters handles the rawness and violence of Alice being sexually attacked—opting to recreate a child’s emotional and mental dissociation, focusing less on the violation than on the mixed messages of adults aware of the abuse (messages ranging from denial and blame to an urge to forget)—are gutting. The reader experiences the full spectrum of Alice’s trauma without the author traumatizing reader or character. Koesters’s deft use of sparse imagery and allusion are a testament to her craft and carry a potency akin to Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye.

In the aftermath of Paddy Nolan’s brutal attack, Marnie’s family, cousin Father John Martin included, sweep Alice into their realm of relative safety. But here, the narrative is not done with Father John. Alice’s trauma too eerily echoes the child from whom he walked away twelve years before, and there is a reckoning. Emotionally and physically incapacitated by his guilt, he is temporarily removed from the church and placed in a facility with a psychiatrist, Sister Camille. The nun helps Father John unravel his past, his years of repressing desires, and not solely his guilt but also his lack of it. When he finally returns home, he is functional but raw with wants: want for reconciliations, want for words left unsaid, want for actions not taken. All are in the past and now impossible. Still, he thinks, “Someone needs to do something. Why doesn’t someone do something?” In his memory, the girl from the rowhouse window answers: “We could do something.”

And there the novel leaves us. Someone must do something. We can do something. So will we?

Miraculous Medal has drawn apt comparisons to Frank McCourt and Ernest Gaines, but there can be no doubt: Adrian Koesters paints a vivid, haunting portrait of Baltimore that is both solely her own and one that speaks to all of us.

About the Reviewer

Chris Harding Thornton holds an MFA from University of Washington and a PhD from University of Nebraska. Her first novel, Pickard County Atlas, will be released January 5, 2021 by MCD/FSG, a division of Farrar, Straus & Giroux.