Book Review

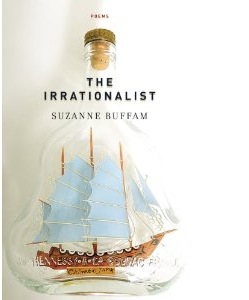

Original, inventive: we want our poets to be bold. We want the poems to add up to more than the sum of their parts. We want the sublime, the open-to-the-bone exclamation of epiphany. And we’d like the poem to be smart but not too intellectual. Why not? In her second book, The Irrationalist, Suzanne Buffam delivers.

Original, inventive: we want our poets to be bold. We want the poems to add up to more than the sum of their parts. We want the sublime, the open-to-the-bone exclamation of epiphany. And we’d like the poem to be smart but not too intellectual. Why not? In her second book, The Irrationalist, Suzanne Buffam delivers.

As if she didn’t get the memo that poems must take themselves seriously, she offers us a dizzying and appealing perspective laced with humor. Poems titled with the word “interior” preceded by a descriptive adjective (Ruined, Infinitive, Telescopic, Dim-lit, Vanishing, Romantic) frame the book. “Ruined Interior,” the first poem, starts with a biblical reference and branches out with attitude:

In the beginning was the world.

Then the new world.

Then the new world order,

which resembles the old one

doesn’t it?

The poem reveals Buffam’s concerns with knowing, telling, and questioning, as well as her unwillingness to accept the easy way out:

Don’t tell me there’s another,

better place. Don’t tell me

there’s a sea

above our dreaming sea

and through the windows of heaven

the rains come down.

In “Happy Hour” the delirious joy of experience is described:

I want to crawl through a honeycomb

Of subglacial passageways,

Shove my head under God’s faucet

And keep chugging until I pass out.

The narrative voice is preoccupied throughout the book with wisdom: understanding what is wisdom and what is not. The poet imparts her own brand of wisdom and relays other’s wisdom as well. Buffam’s wisdom is composed of smoke signals from an imagined world. She is declaring her universe. In the telling, in the declaration and formulation of the language, the narrative voice speaks directly to us, as in “Placebo”:

It is possible to die of fright after

being bitten by a nonvenemous snake.

Also, in some cultures to kill a man

by pointing a bone at his heart.

In “Amor Fati” the narrative voice speaks confidently, matter-of-factly, as if giving solid advice: “There is no such thing as a dream that comes true. / Every dream is already true the moment it is dreamed.” In “The Solitary Angler” the poet warns us wisely, “There is no greater calamity / Than to underestimate the strength of your enemy.”

Sometimes her wisdom is like a Zen koan: “Experience taught me / That nothing worth doing is worth doing // For the sake of experience alone” (“The New Experience”). At other times her plain-spoken advice is both scientific and mocking: “The sun came out. It was the old sun / With only a few billion years left to shine” (“The New Experience”).

Buffam’s individualistic stance is evident in the energy of her syntax: “I cannot tell you what I saw. / My catastrophe was sweet // And nothing like yours” (“If You See It What Is It You See”). In “The Solitary Angler” the speaker proclaims, “One day I woke up / And did not fear the old gods.” In a poem about the potentiality of life, “Death Toll Rises in Black Sea Sinking,” Buffam writes:

From where I stand

The world is a warm blue bath

I can wash my feet in it.

I can pick a cloud

Any cloud

And watch it nudge a mast

Across a harbor of light.

“Little Commentaries,” the second and longest section of the book, is composed of seventy-four poems with the title On______ (“On Metaphor,” “On Abstract Expressionism,” “On Clouds,” “On Attachment,” “On Shortcuts”). Buffam’s short attention span packs a laser-like focus. These short poems, life lessons from an uncanny seer, often consist of an observation or an observation turned on its head. Here she engages the world tersely, presenting us with a quick image or idea, then pulls quickly from the poem. Some of these poems are so short that they are about dismounting (as Jack Gilbert calls the act of ending the poem) the moment they mount.

In “On Last Lines” she writes: “The last line should strike like a lover’s complaint. / You should never see it coming. / And you should never hear the end of it.” In “On Beauty” she notices a common phenomena and its rare meaning:

Noon comes hammering down on the harbor

Ringing all its bells.

Masts tip

This way and that

Scratching God’s name on the vault.

In the prose poem, “The Wise Man,” that starts out the third section of the book, Buffam meditates upon what could be her own process:

I find it hard to sit still very long before I get up and wander the halls in my hat for example. On the other hand I stay warm and keep moving. Could these ways be the same way? A wise man could tell you.

Throughout the final section of the book, Buffam’s voice is more personal, and the poems are more likely driven by narrative. In “Trying,” about getting pregnant, she writes plainly: “We bought a new set of sheets for the bed. We bought a thermometer and a book.”

In the final poem, “Romantic Interior,” she speaks directly of despair and of hope:

There’s a hole in the ground

Where my house used to be.

A hole in my head

Where my heart used to be.

I’m climbing a hillside.

A green patch of laughter.

To experienced readers, Buffam gives back an inkling of the Zen notion of beginner’s mind. When you read for the first time poetry that really surprised you and opened your eyes to what poetry is capable of—perhaps James Tate’s “Deaf Girl Playing” or Charles Simic’s “Stone”—you might have asked yourself in rising expectation, “Poems can do this?” Regarding Buffam’s work, I agree with a child’s report on a book she enjoyed: “I liked it because it’s a funny book and long.”

About the Reviewer

John Whalen is the author of In Honor of the Spigot (Gribble Press Chapbook Award, 2010) and Caliban (Lost Horse Press, 2002). He is an abstract painter working with acrylic on canvas and makes a living in computer security. His poems have appeared most recently in the Gettysburg Review, the Laurel Review, Puerto del Sol, CutBank, Crab Creek Review, and Barrow Street.