Book Review

In Randa Jarrar’s story “Lost in Freakin’ Yonkers,” the protagonist, Aida, goes to the library and searches its computer system for books with the following terms: “Arab,” “American,” “women,” and “fiction.” Originally from Egypt, Aida is living in America, in her third trimester, and trying to figure out if she should marry her baby’s father. Disowned by her father, she has an uneasy but functional relationship with her mother, who confesses to having previously considered some extreme methods to keep her daughter chaste. Aida’s boyfriend is a drunk. She is, in many ways, alone, and she is looking for some fiction to help her feel less alone. Aida narrates:

In Randa Jarrar’s story “Lost in Freakin’ Yonkers,” the protagonist, Aida, goes to the library and searches its computer system for books with the following terms: “Arab,” “American,” “women,” and “fiction.” Originally from Egypt, Aida is living in America, in her third trimester, and trying to figure out if she should marry her baby’s father. Disowned by her father, she has an uneasy but functional relationship with her mother, who confesses to having previously considered some extreme methods to keep her daughter chaste. Aida’s boyfriend is a drunk. She is, in many ways, alone, and she is looking for some fiction to help her feel less alone. Aida narrates:

I want to explain . . . that I need this, need to go to school and have a father for the kid, need to be able to tell the God, on the day of judgment when I crawl out of my grave and I’m all alone and shards of sky are crashing down on me, that—look, dude—I tried.

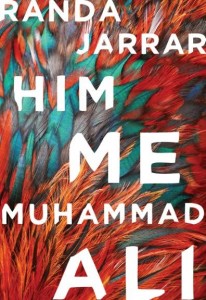

Unfortunately, her search yields no results. If only she had been able to check out a copy of Him, Me, Muhammad Ali, Randa Jarrar’s arresting collection of stories (as well as her novel A Map of Home), Aida would have found some heroic Arab men and women trying to forge identities for themselves. Here are characters who have to deal with sometimes hostile cultures (whether they live in an Islamic society or not) as well as with the same kinds of issues women and men of all stripes share: trying to find their place in the world.

Jarrar’s characters are Muslims, mainly women, usually not living their lives in lockstep with the Quran, but feeling grounded in their religion and culture and home nonetheless. Take, for example, the Palestinian family living in the United States in “Accidental Transients.” The story is narrated by Dida, who at twenty-nine is acting as a mother for her brothers:

We were the kind of Muslims who pay for tax breaks (Baba), Nintendo DS games (Jaseem), anatomy coloring books (Weseem), pussy (Abe), and a guilt-free conscience to move the fuck out of the house (Yours Truly). The only thing keeping us from being outright atheists is that none of us had ever eaten pork. We were bound to God through the absence of pig grease.

“Accidental Transients” exemplifies the wisecracking voice in many of Jarrar’s stories. It can be a difficult voice to master, but “Accidental Transients”—like “Lost in Freakin’ Yonkers”—manages easily. Other stories possess a more measured voice, but always with a strong sense of irony.

Just like Dida, the protagonist of “Building Girls” doesn’t want to strike out from her current surroundings. Aisha lives in a seaside town in Egypt and manages a small apartment building, the same one in which she grew up. There she eventually encounters an old childhood friend, also a single mother, who now lives abroad. They quickly bond. The many layers of the story reveal themselves as Aisha and Perihan navigate the various apartments and floors of the building, eventually culminating in a night that could get them both prosecuted. At one point, Aisha dismisses reading books where the protagonists go out to the world and then return to the homeland, changed. This first seems to reveal a yearning to escape, but eventually it emerges that Aisha is dismissive of ever leaving home at all. She seems to be a Muslim woman truly aware of, even comfortable with, her restricted life—and raising her daughter the same way.

Unlike Aisha, though, the bulk of the characters in Him, Me, Muhammad Ali are displaced in some form. Kinshasa, in the title story, is a biracial woman—half black and half Egyptian—who returns to her mother’s homeland to spread her father’s ashes. “When people suddenly leave a place,” Jarrar writes, “they begin to believe they have no history.” A story nominally about a father and daughter becomes more about a mother and daughter, and Kinshasa, named for the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo where her parents met, discovers something about herself in both the “endless white and yellow sand” around Cairo, as well as inside a tomb-like closet that contains her mother’s things.

There is also quite literal displacement in “The Story of My Building,” about a Palestinian boy and his family living in the Gaza Strip, and in “A Frame for the Sky,” which follows a Palestinian man who is forced to settle in New York after not being allowed back into Jordan. More metaphorically, the mothers and daughters in “Asmahan” are displaced from their relatively comfortable existence when they get into a car accident, injuring a poor girl on their way to a literary event. The jam-packed streets of Cairo, which Kinshasa also encounters, lead to the accident.

Finally, displaying another side of Jarrar’s storytelling ability, the collection is bookended by two tales of magical realism, “The Lunatics’ Eclipse” and “The Life, Loves and Adventures of Zelwa the Halfie.” In the former, a charming fabular tale, Qamar (an acrobat) and Hillel (a student so successful the government has given him his own rocket) both obsess over stealing the moon. “The Lunatics’ Eclipse” manages a feat at which other similar magical realism stories sometimes fail: it is odd without being cute, and not exotic for the sake of being exotic. “Zelwa” is in a similar vein as the raucous journal of a woman who is also half-ibex, imagining a world of “halfies” and pulling more out of the idea than just a metaphor. A third magical realism tale appears halfway through the collection, “Testimony of Malik, Prisoner # 287690,” a story posing as a transcript of an interview with a kestrel, who gives a (literal) bird’s eye view of the Middle East.

In the reductive American political mind, the Middle East is often only the source of oil and terrorism. Neither appears in this collection, with the exception of a passing reference to a hijacker uncle in one story, and the comparison, in another, of the World Trade Center to a two-fingered peace sign. After reading the story “Him, Me, Muhammad Ali,” it seems almost gauche to even mention oil and terrorism—such is the verve of Jarrar’s edifying stories, writing a world which many more not only should be reading, but need to read. Let’s hope that, unlike Aida, they can find a copy at their local libraries.

About the Reviewer

Greg Walklin is an attorney and writer. His fiction and nonfiction have appeared in Midwestern Gothic, The Millions, Necessary Fiction, Palooka, and Pulp Literature, among other sites and publications. He and his wife, Tiffany, in live in Lincoln, Nebraska with their Yorkshire terrier, Mocha.