By Colorado Review Associate Editor Cole Konopka

By Colorado Review Associate Editor Cole Konopka

This past October a friend and I went to the 2017 American Literary Translators Association conference in Minneapolis, each of us having had some experience in the art of translation and a desire to leave town for the weekend. I hadn’t expected much from the trip beforehand, but as I went to panels and talked to translators at the conference, I realized how much translation had to say about poetry, as well as nonfiction and hybrid works—about creative writing in general. When I noticed the care and attention these professional literary translators gave to individual words, to sentence structure and paragraph rhythm, when I heard the love in these translators’ voices as they discussed some of their favorite writers, it reminded me of the literary passion of creative writers. It reminded me of the joy in language that brought me to a place of writing and translating in the first place.

But perhaps more important than the gemütlichkeit of being around people who had a particular interest in words was the mutual recognition that the world is full of a diverse array of literary perspectives, and to limit myself to primarily American writers would be an arguable mistake. The United States is not the center of the world and neither is its literature, yet we often act under this Anglocentric assumption. Translators widely lament the fact that of all the books published in English, only about three percent are works of translation, with close to only 0.7% consisting of literary fiction and poetry.

This isolationist issue, which goes back centuries in the history of letters, largely stems from misunderstandings about translation, as well as from an overestimation of originality. Some consider translation by definition a slanderous act on imagination, while others think translators less creatively talented than writers of “original” work. What assumptions underlie this depreciation of translation? What prevents us from learning from international experience, as if problems elsewhere don’t resemble problems at home, or though world neighbors can’t exchange creative solutions to language and life?

Translators hold themselves accountable for every word choice, just as poets and writers in any native language. However, because translation represents both an extension of an original work and a unique creative production, some underestimate the degree of effort and originality involved. We maintain the false notion that literature must, or can somehow be completely original, pure, a work of genius, without questioning what exactly those terms mean, and how no writing is devoid of influence. Because of my experience as a translator, I can personally speak to the sheer force of intellectual effort it requires. Writing results from work and so does translation.

Limiting assumptions about literature do not benefit us in today’s global world. I believe we as readers have much more to learn from translation than we’ve given it credit for. If at a loss for a new poetry book to read or gift this holiday season, I highly recommend one of the following four collections of poetry translations:

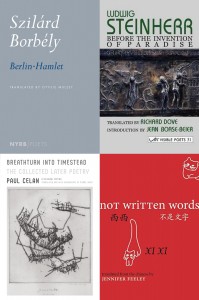

Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poetry of Paul Celan, translated by Pierre Joris, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2014.

Hefty as it is thorough, this bilingual edition of Paul Celan’s last five poetry collections offers a whirlwind of language that only the later Celan could conjure.

Berlin-Hamlet by Szilárd Borbély, translated by Ottilie Mulzet, New York Review of Books, 2016.

A short list nominee for the 2017 National Translation Award in Poetry, Berlin–Hamlet is as wrenching as one would imagine a book to be that contains fragments of Kafka’s letters in some of its lines.

not written words by Xi Xi, translated by Jennifer Feeley, Zephyr Press, 2016.

This bilingual edition is the first collection of Xi Xi’s poetry in English, including works written between 1961-1999.

Before the Invention of Paradise by Ludwig Steinherr, translated by Richard Dove, Arc Publications, 2010.

Richard Dove’s English rendering of Steinherr maintains the quiet philosophical mind of this postwar, contemporary German poet.