By Nathaniel Barron, Colorado Review Editorial Assistant

I recently received a book to review for the Center for Literary Publishing. I was excited; the author had impressive publications and credentials, and the blurb on the back cover was from a recent Pulitzer Prize–winning author (who shall henceforth be referred to as PPWA). According to PPWA, this was one of the finest books of the year. According to PPWA, it was simply “unforgettable.” How exciting for me! I thought. I’d get to have my name up there on the CLP blog, point to said blog when the book hit the New York Times best-sellers list, and say that I (and the CLP) knew about it way before it was cool.

But as I read the book, I started to have this sinking feeling: the book just wasn’t good. Keep reading, I told myself. Pretty soon the narrative will open up and you’ll see exactly what PPWA was talking about. But then I finished the book, and it still wasn’t good. That’s when the doubt set in. You’re obviously missing something, said a voice in my head. What the hell do you know about good literature? You wouldn’t know a good book if it was—and so on and so forth. I was conflicted. I read the book again, hoping I would finally see what I was missing. Still nothing. I considered writing a positive review anyway. After all, it wasn’t the author’s fault that I’m just obtuse, right?

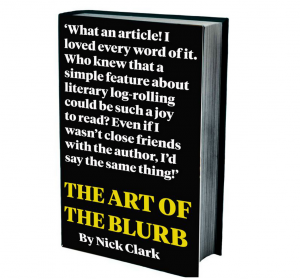

The debate about book blurbs is not a new one. Novelist Bill Morris claims that they don’t really matter, that they’re “a bit like the vermouth in a martini: can’t do any harm, might do some good, so let’s have it.” Literary agent Sharon Bowers claims they are a necessary evil; while most blurbs say more about the connections of the author and the publishing house than anything else, some of them have the potential to make an important connection with the reader. Bowers defends blurbs on the basis that somewhere in the “the sea of blurb babble . . . sometimes a spark will burst from the darkness.” Stephen King claims they’re fine as long as you do like he does and blurb only for books you’d actually recommend to your fans. Just don’t blurb a book for a friend, he says, for “that’s the road to hell.”

These opinions all put an awful lot of faith in the average reader. They assume that we will be able to tell which blurbs are simply marketing by the publishing house and quid pro quo favors between authors and which are actually honest recommendations from one book-loving soul to another. But look at me—I’m supposed to be an educated reader, and that PPWA blurb had me considering whether I should just write a positive review anyway because I clearly didn’t understand the book. And what if someone then read my review and the blurb from PPWA and thought, Well, who am I to disagree? Then what if that someone writes another positive review and pretty soon people are thinking this is a book they need to read? Now, I’m drastically overstating my influence here, of course. Eventually someone with real literary chops—someone who’s far less gullible and suggestible than I am—would come along and put an end to all this nonsense, to expose the emperor’s nudity, as it were. Right? Or is it conceivable that a book might get passed along because it’s just inscrutable enough to make a sufficient number of smart people doubt whether there’s something they’re just missing?

I’m a scientist at heart, so when confronted with these big, scary questions I always go running back to cold, hard empiricism. And what did I find?  Well, according to this recent study in Science, which examined how up-voting a comment in an online forum affects the likelihood of subsequent up-votes from other users, one positive rating leads to a thirty-two percent increase in the likelihood of a subsequent positive rating. Thirty-two percent! The funny thing is that it doesn’t work the same way for negative ratings. Unwarranted down-votes (i.e., those given simply because others did so previously) eventually get corrected by the crowd, but this does not apply to positive votes. It seems we are quite good at recognizing when people are being unfairly negative, but not when they are being unfairly positive! Over time, this imbalance led to positive herding effects that resulted in ratings that were, on average, twenty-five percent higher than they would have been in the absence of this social influence bias. In other words, one in four books gets a positive review that it doesn’t deserve. This shouldn’t be surprising. We’re social beings, after all. We seek harmony and to have our opinions validated by those of others.

Well, according to this recent study in Science, which examined how up-voting a comment in an online forum affects the likelihood of subsequent up-votes from other users, one positive rating leads to a thirty-two percent increase in the likelihood of a subsequent positive rating. Thirty-two percent! The funny thing is that it doesn’t work the same way for negative ratings. Unwarranted down-votes (i.e., those given simply because others did so previously) eventually get corrected by the crowd, but this does not apply to positive votes. It seems we are quite good at recognizing when people are being unfairly negative, but not when they are being unfairly positive! Over time, this imbalance led to positive herding effects that resulted in ratings that were, on average, twenty-five percent higher than they would have been in the absence of this social influence bias. In other words, one in four books gets a positive review that it doesn’t deserve. This shouldn’t be surprising. We’re social beings, after all. We seek harmony and to have our opinions validated by those of others.

Now, there are obviously some caveats to applying these results directly to the literary world. First and foremost, writing a thoughtful review is not the same as quickly clicking a button. If all I’d had to do was just “up-vote” the book or not, I probably would have just given it a thumbs up and moved on. But where my brain (and conscience) gave me pause was when I sat down to write the review and realized I couldn’t think of a good thing to say. Also, we’d expect people in the field of writing and publishing—people whose livelihoods depend on the credibility of their words and their opinions—to take a bit more care in deciding where and when to dole out recommendations and positive reviews. Or maybe we can’t expect that. Unless I was really missing something, PPWA clearly wrote a blurb that he/she didn’t fully stand behind. (My guess is that PPWA took a walk down that road Stephen King was talking about.)

So what does it all mean? Well, maybe it means we should never read the blurbs on the back of the book, even if we’re confident in our ability to see them as the marketing tools they are. Maybe it means we should err on the side of negativity (a conclusion which makes me sad). In any case, it suggests that we should be more conscientious about our opinions, and more conscious of the social forces that influence them.

“Like” this if you agree.

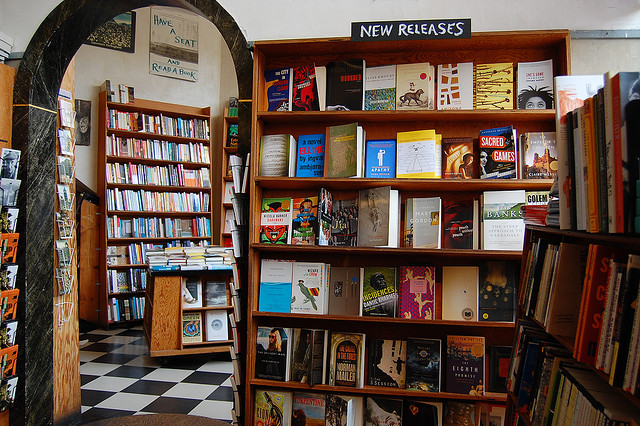

Images by Patricia Glowgoski (bookshelf), The Independent (book cover).