by Marie Turner, Colorado Review Editorial Assistant

I’ve been thinking lately about the issue of taste. I think it’s been on my mind because of recent instances in both my professional and student lives that have made me think about how when we publish (or attempt to publish) something, there are an extraordinary number of quite subjective variables that come into play regarding its ultimate success or failure. By success and failure, I mean not only whether something gets published, but also the fate of the published work once it is in print. Taste is rather mysterious, yet plays heavily into both.

I’ve been thinking lately about the issue of taste. I think it’s been on my mind because of recent instances in both my professional and student lives that have made me think about how when we publish (or attempt to publish) something, there are an extraordinary number of quite subjective variables that come into play regarding its ultimate success or failure. By success and failure, I mean not only whether something gets published, but also the fate of the published work once it is in print. Taste is rather mysterious, yet plays heavily into both.

I’m a new writer and MFA student, but my current “day job” is as a postdoctoral research fellow in the sciences. In this capacity, a few months ago, I finally submitted a manuscript that I and seven other colleagues had been working on for the previous two years. I felt great about it. I really did. A ton of work went into the experiments, and I had edited the paper meticulously, as had each of my seven co-authors. I had even forced other qualified, yet more objective parties to review it to ensure we weren’t indulging in creative myopia. I felt good about the journal to which we were submitting, which was both influential but also a perfect match in terms of scope. I thought, That’s all it takes, right? A great paper and an appropriate forum. The reviews came back. The first reviewer felt largely as we did: that the work was important and the paper well-constructed. The second reviewer hated it. Like hated it. It was as though, rather than a paper written about plant metabolomics, I had written a detailed argument about everything wrong with the reviewer’s mother. The review was convoluted, which suggested to me that somewhere early on in the process, the person became so blinded by something he disliked that he failed to read much of it accurately at all. Bizarrely, he even suggested we should have carried out a different research project altogether, which is such an odd thing to say that I am still trying to wrap my head around it. The bottom line was that the paper was accepted with certain revisions. I was still trying, however, to move past the utter incongruity of the responses and what, ultimately, I think can only be chalked up to differences in taste. How this guy’s taste could be so strange still eluded me.

But then I thought of a recent experience in my MFA coursework. Not so long ago, I read a book for a class. I am not going to say what it was because I hated this book. This experience in and of itself was kind of disturbing for me. I am not, as the kids say, a hater. In fact, though I rarely fall in love with books, I often make it a point to fall in love with something about a book, even when I don’t love it as a whole. That is, I try to walk away with a little bit of beauty or learning or both. Otherwise, I think, why bother? No dice with this one. In class, however, I discovered that not only did no one else hate the book, many of my classmates loved it. It made my head hurt. I had scoured the book looking for something that I could love but failed. My taste would not allow me to do this. For reasons that I am still trying to tease apart, I not only disliked the book, but, like the reviewer of my paper, I wished that the author would have written an entirely different book. I still don’t know exactly why I was so deeply offended by the book’s existence, but I was.

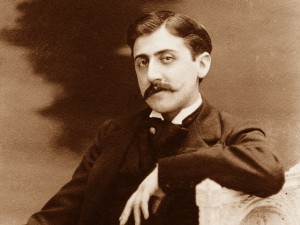

So what is this thing taste, aside from what we do and don’t like putting in our mouths? Where does it come from? Even when we are speaking literally about things we enjoy eating, it’s a question that continues to baffle neurobiologists. An area of this research that is even less well-understood is the investigation into the “Proustian experience” (first coined in À la Recherche du Temps Perdu), which is also often referred to as “involuntary memory.” It is the idea that certain things, such as the odor, taste, and texture of the foods we eat, can trigger experiences that are emotionally intense and sometimes directly associated with things that have happened to us in our past. If the memories or associations are negative, it may blind us to the health benefits of a certain food or perhaps create a strong enough gag reflex for us that we stop it eating altogether. We may even attempt to convince others that they shouldn’t eat it.

So what is this thing taste, aside from what we do and don’t like putting in our mouths? Where does it come from? Even when we are speaking literally about things we enjoy eating, it’s a question that continues to baffle neurobiologists. An area of this research that is even less well-understood is the investigation into the “Proustian experience” (first coined in À la Recherche du Temps Perdu), which is also often referred to as “involuntary memory.” It is the idea that certain things, such as the odor, taste, and texture of the foods we eat, can trigger experiences that are emotionally intense and sometimes directly associated with things that have happened to us in our past. If the memories or associations are negative, it may blind us to the health benefits of a certain food or perhaps create a strong enough gag reflex for us that we stop it eating altogether. We may even attempt to convince others that they shouldn’t eat it.

My suspicion is that when it comes to what we read, something similar may be at work. Something about who I am, the sum of my collective biological machinery and experience, is what caused me to have such an intense negative reaction to a piece of literature that other people found to be beautiful and important. Something about who my reviewer was made him read my science and roll his eyes. I think part of taste also has to do with our very proximate experiences; that is, maybe my reviewer was having a bad day or was really hungry or maybe someone he loved was really sick and he just lost patience for everything in that moment. I think this happens to all of us at one time or another.

Some of these reactions, I think we can control. I do think a practice of searching for redemptive and useful things in the works that offend us most is a good exercise in understanding not only why certain works of literature are not attractive to us, but also what we can do to avoid bad habits in our own writing. I also think it behooves us to consider our emotional states at the time of our readings and give whatever we read the benefit of the doubt for as long as we can. This helps us be constructive and discover things that we can apply to our own work (plus—wouldn’t we like the same from whoever is reading our own writing?). I also think that there is something to be said for sheer diversity of consumption. What happens when I eat only foods that I love? What happens when we learn only from only writing we are comfortable with? The answer: We become less fit, less flexible, and less able to evolve in terms of both life and writing. Sigh. Does this mean I have to re-read that book?

“Figs” image by Mary Beth Griffo Rigby