Book Review

Nature can be good for us. In a recent study, Japanese scientists found that walking through a forest or other wooded area for a few hours reduced concentrations of the stress hormone cortisol in subjects and lowered blood pressure. Other studies show green areas alleviate anxiety and depression.

Nature can be good for us. In a recent study, Japanese scientists found that walking through a forest or other wooded area for a few hours reduced concentrations of the stress hormone cortisol in subjects and lowered blood pressure. Other studies show green areas alleviate anxiety and depression.

Nature can be good for poets, too. The poet’s skills of noticing and reflecting—and the transcendent potential of metaphor—thrive in the wild, and where wild and cultivated intersect. European transplants early on embraced and produced meditations on nature, morphing from the romantic tradition of England’s hills and lakes in the new landscape of dark woods, broad fields, steep mountains, and fast and slow rivers to produce original verse. As an Anglo-American who labels herself a naturalist and has taught environmental education, I’ve benefited physically and emotionally from unhampered access to nature across the country’s deserts, swamps, mountains, forests, fields, meadows and plains. After reading more than a hundred poems from African American writers, I see how shared—and how unique—experiences of nature are across temporal, geographical and social constructs of race.

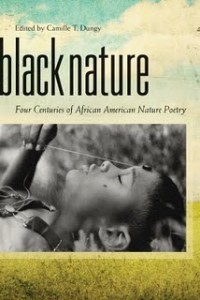

Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry, edited by Camille T. Dungy, provides 180 windows from 93 poets onto views of nature. Capturing in six lines the complexities of history, race and place, E. Ethelbert Miller, in “I Am Black and the Trees Are Green,” offers:

so you point

and say the woods are beautiful

like men standing on shores

of Africa enjoying the sun on their skin

the white sand touching the water blue

the new slaves as invisible as conversation

Dungy explains in her introduction to Black Nature, “For years, poets and critics have called for a broader inclusiveness in conversations about ecocriticism and ecopoetics . . . African Americans, specifically, are fundamental to the natural fabric of this nation but have been noticeably absent from tables of contents.” Through the immediacy of poetic language, the poems in Black Nature land the reader in the poet’s particular experience of herself or himself in a particular place. Allow, for example, Thylias Moss’ “Sweet Enough Ocean, Cotton” to bring a cotton field to the forefront:

I haven’t seen the sea before

but it must be easy to love

because even without ever seeing it before

I call the blown-open cotton a sea,

I call moving through the rows

my attempt to walk on rough water.

I’ve seen the sea often and never walked through a field of cotton until reading Moss’ poem. Moss continues:

…This small field

seems bigger than the sky,

and is the sky for ants. It’s just

how the cotton carries you,

delivers you on a rocky shore,

shipwrecks you,

strands you

She concludes:

Few months after we planted it,

I called the pink blooms of cotton before it ripened

an assault of endless sunset on the ocean.

Essays introduce each of the anthology’s ten sections or “Cycles” as Dungy calls them. In Cycle Two, Ravi Howard points out that poets extract only experience from a place, “leaving the natural place intact for others who will come after . . . poets modify and rearrange nature on the page.” Naturalists are observers and the poems in Black Nature reveal that. Natasha Trethewey writes in “Monument” of the ants “busy / beside my front steps, weaving / in and out of the hill they’re building.” She recalls, “At my mother’s grave, ants streamed in / and out like arteries, a tiny hill rising // above her untended plot.”

Trethewey’s poem appears in Cycle Five, “Forsaken of the Earth,” not in Cycle Four, “Pests, People Too.” Cycle Four includes poems about insects, pesky and otherwise. The anthology’s organization detracts sometimes from the poems. The placement of the poems can feel forced and arbitrary, an attempt to categorize humans’ relationship and, consequently, the reader’s response to the works. Organizing the poems geographically might have made a meaningful reference for the reader. Settings in the poems range across the United States and pull from mid-Atlantic and Southern regions, areas that could benefit from greater understanding. In “potters’ field,” Cynthia Parker-Ohene arranges words to hold anger, loss, and beauty “in the throat of crownsville, maryland.” How informative it would be to have other writers’ poems of the mid-Atlantic region nearby to peruse as a cluster.

We are all vulnerable. Nature sometimes makes us feel more so, safer and more endangered, depending. The times I have felt fear in nature was as a hiker in a woman’s body, isolated from other women. Black Nature includes poets’ views of the body in nature. In Cycle Two, “Nature, Be with Us,” James A. Emanuel’s poem “For a Farmer” offers a quiet, lovely portrait of a man:

Something flows with him in stubborn streams,

And in the parted foliage something lives

In upright green, stirred by the rhythmic gleams

Of his hoe and spade. From worn-out arms he gives;

The earth receives, turns all his pain to soil,

Where he believes, and testifies through toil.

Langston Hughes (1902–1967 ), in “Lament for Dark Peoples” writes, “I lost my trees. / I lost my silver moons. // Now they’ve caged me / In the circus of civilization.” In Black Nature Hughes’ poem is in Cycle Five, “Forsaken of the Earth,” after Emanuel’s poem. Reading the poets chronologically generates different responses.

Like the florist selecting blossoms for her bouquet and arranging something pleasing, an anthologist operates from instinct and experience as she weighs her choices. These minor organizational quibbles with Black Nature show how affecting the anthology is. Black Nature cannot be dismissed. The range of classic poets (Dunbar, Wheatley, Giovanni, Toomer) with contemporary (Sean Hill, Afaa Michael Weaver, Toni Wynn), and the breadth of styles delights the reader and honors the richness of the American literary tradition. Undoubtedly, Black Nature will be used as a college text but it is much more than that: a collection of poems about nature, our place in nature and our response to nature, provocative, inspiring, and pleasing. Evidence from one of my favorite poets, Anne Spencer, from “Requiem”:

Oh, I who so wanted to own some earth,

Am consumed by the earth instead:

Blood into river

Bone into land

The grave restores what finds its bed.

About the Reviewer

Born in Iowa, raised in Washington, DC and Nevada, Alexa Mergen lives in Sacramento. Poet and essayist, she's the author of the brief history From Bison to BioPark: 100 Years of the National Zoo, the chapbook We Have Trees, and co-editor of the 45th anniversary California Poets in the Schools anthology What the World Hears. Her poems appear most recently in Dogs Singing: A Tribute Anthology. Her book reviews can also be found in American Studies International, High Country News and Rattle.