Book Review

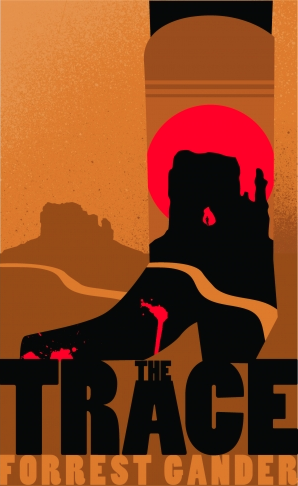

When a novel begins with a man sitting on a filled toilet, pants at his ankles, listening to his wife being murdered in the next room, and, moments later, that same man crouching bare-assed inside the vanity seconds before his own death, you have one of two options: you can turn away from the discomfort of it all, or laugh a little nervously, turn the page with one eye open, and read on. Forrest Gander’s novel The Trace opens just this way and subsequently alternates between poetic details of the breathtaking desert scenery along the Texas–Mexico border, raw and painful exchanges between a husband and wife, and gruesome details of a murderous villain that would make the likes of Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce proud. With a poet’s eye for the minute and barely-there, Gander draws the reader into a world filled with benign details that by themselves may have gone unnoticed, but in the aggregate form the foundation of all that we know to be true.

When a novel begins with a man sitting on a filled toilet, pants at his ankles, listening to his wife being murdered in the next room, and, moments later, that same man crouching bare-assed inside the vanity seconds before his own death, you have one of two options: you can turn away from the discomfort of it all, or laugh a little nervously, turn the page with one eye open, and read on. Forrest Gander’s novel The Trace opens just this way and subsequently alternates between poetic details of the breathtaking desert scenery along the Texas–Mexico border, raw and painful exchanges between a husband and wife, and gruesome details of a murderous villain that would make the likes of Edgar Allan Poe and Ambrose Bierce proud. With a poet’s eye for the minute and barely-there, Gander draws the reader into a world filled with benign details that by themselves may have gone unnoticed, but in the aggregate form the foundation of all that we know to be true.

Ambrose Bierce is an apt reference point, as Dale, the protagonist, is on a journey tracing the last steps of Bierce, an American journalist and storyteller, who disappeared during the Mexican Revolution. Dale, a historian, and his wife, Hoa, a ceramics artist, drive seemingly endless hours through the pale desert landscape along the border, stopping here and there at the many places Bierce is believed to have died or been killed. The couple is also embarking on a journey of recovery after an unnamed accident involving their grown son, Declan, has left them estranged both from their son and each other. Throughout the journey, Dale and Hoa listen anxiously for their cell phones, for any word from Declan, each wavering on the edge of an emotional cliff where they can either cling to the solidity and comfort of their many years together, or free-fall into the abyss of grief and despair.

Against the backdrop of Bierce’s history, Gander juggles the storyline of Dale and Hoa with that of a ruthless drug dealer named El Palomo, or the “cock-pigeon.” Gander seems to take great pleasure in El Palomo, a character who personifies a growing sense of doom, yet who also provides the reader with dark comic relief from the emotional strain of the couple. El Palomo gets his name from a medical condition that makes his head bob “in the weirdest way, uncontrollably, like an ornament on the hood of a car going over bad road.” While the tic “freaked out people who weren’t used to it,” it is El Palomo’s macabre calm and humor that are the most chilling. While his men dismember a corpse, El Palomo carefully skins the face off the head and stretches it around one of the soccer balls he keeps in the bed of his truck. Grinning, the killer holds up the face-wrapped ball and declares, “Creo necesitas un corte de pelo” (“I believe you need a haircut”), as two of his men wonder “which of them will be given the responsibility of holding the fucking ball while El Palomo drove.” Gander’s eye for detail here makes one question nervously how on earth he could describe such a horrific action quite so vividly. Equally disturbing is the fact that, like the snakes in the desert that Dale fears, El Palomo and his men slither ever closer toward Dale and Hoa until their paths eventually and dangerously intersect.

Gander is also a poet and these talents are evident in his incredible control of imagery and pacing as he describes his characters and setting. Whether it’s Hoa firing her clay pots, Dale running through the desert heat, or, later, Dale sinking into a delirium from thirst, the reader witnesses not just the external physical action, but viscerally experiences each drop of sweat, each muscle twinge, and each cactus prick. Because of this sense of immediacy and intimacy, the reader feels not like a voyeur, but more like the characters’ shadows, moving in tandem through time and space. Gander also trains his expert eye for detail on the desert landscape. While Dale may observe that “[t]here was a living, moving world out there in the desert, utterly invisible to him . . .” Gander sees everything and deliberately paints every nuanced detail of the environment that might not otherwise be noticed. Though at times the descriptive passages feel a bit indulgent and have the undesired effect of slowing the narrative, more often they are beautiful and effectively mirror the complexities of the emotional dynamics of the story.

An intriguing structural feature of The Trace is Gander’s insertion of seven short lyric poems, each opening a section of narrative prose. The poems feel mysterious but ultimately reveal the emotional reality of the family history of Dale, Hoa, and Declan, the details of which are otherwise only hinted at throughout the larger narrative. Like the poems in Gander’s collection Torn Awake (New Directions, 2001), these lyrics also hint at the complexities of one’s relationship with family and with the self. Full of startling imagery, the poems in The Trace further reveal Gander’s skill in employing words to create memorable sights and sounds. In “The Departure” he writes, “Perturbed by a bird-punctured cicada / clattering in circles on the driveway, / he came into the house feeling ill . . . .” Keeping with the theme of hidden dangers, we learn near the end of the poem that the man is actually an intruder listening in on a woman and child telling stories at naptime. Each of the poems plays with this idea of a presence that is barely there but is authentic and powerful and yearns to be discovered.

At times The Trace requires patience, particularly if you are unfamiliar with the geography of the region between Texas and Mexico, and I found myself wishing the editors had provided a map to reference as the journey progresses. But in the end, such patience is rewarded. The novel manages to capture the intimate realities of marriage, the complexities of being a parent, and the minutiae of bodily experiences that, while at times are unpleasant, are sometimes the only evidence of being alive. Like the surrounding mountains of metamorphic rock that “are slashed by dark plutonic seams and glimmering quartz veins,” Gander builds his narrative with layer upon layer of detail that grows, imperceptibly at times, and results in a subtly beautiful landscape of a life accomplished and endured by steadfastly putting one foot in front of the other. It is these seemingly imperceptible realities that make the search for the truth about Bierce, and, more importantly, the search for lost love, all seem possible.

About the Reviewer

Susan Donnelly Cheever is an English teacher and poet. She lives in Concord, Massachusetts.