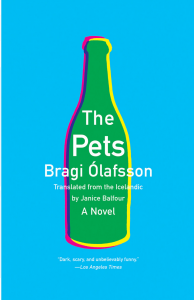

Book Review

Emil Halldorsson, the protagonist and narrator of Bragi Ólafsson’s Icelandic-language novel The Pets, makes an observation early in the book that frames this peculiar, off-kilter story: “sometimes it’s as if people and objects are put in a certain place on earth just to suit the whims of some eccentric; as if someone up above is amusing himself by arranging us as he likes, contrary to common sense.” An eccentric god’s actions is an apt metaphor for the plot of The Pets. Throughout this novel, seemingly random and often dangerous events converge, sending the main character hiding under his bed, watching the world swirl around him.

These chaotic events begin after Emil wins a substantial amount of money in the lottery and treats himself to a buying spree in London. On the flight back to Iceland, he spies a young woman named Greta, an acquaintance from his youth. She immediately becomes the focus of his amorous attention. Also on his mind is news he heard from a neighbor: a strange man in an anorak had knocked on his door the previous day. In this three-part novel, we later meet the man in the anorak as he weaves his way through Reykjavik, drinking too much, getting into fights, and periodically calling Emil’s apartment.

In the duty-free airport shop, Emil searches for the elusive Greta, noting that he can’t see her because of the hoard of “consumer crazed Icelanders,” yet he joins their ranks, purchasing expensive liquors, chocolates, and cigarettes. Eventually, he meets Greta outside the airport. They talk and arrange to meet later for drinks.

As Emil arrives home, the mystery man in the anorak—whom we know has just stolen money in a bar scuffle—is closing in on him. As part one of the novel nears its conclusion, Emil makes coffee, notices how he is surrounded by elderly people in his building, and thinks about how many middle-aged divorced children still live with their parents. Then, as Emil’s water boils, the capricious god of The Pets seems to take full control of the hapless protagonist as part two of the novel begins.

The mysterious man in the anorak is Havard Knutsson, who was once a roommate of Emil’s in London and was later sent to a mental institution in Sweden for violent behavior. As soon as Emil sees Havard on his doorstep, Emil tries to escape his own apartment. With no other option, he hides under the bed. Havard is undaunted when no one appears to be home and enters through a window. Emil watches from beneath the bed as Havard gradually takes control of Emil’s world. Havard listens to Emil’s music, drinks his liquor, eats his food, and masturbates in his bathroom. He is an unsavory character who is “not interested in anything,” Emil reflects, “unless it was forbidden or contained the highest percentage of alcohol.” Through a series of flashbacks, Emil reveals a more solid picture of Havard’s problems and remembers how the man’s erratic behavior ended in the senseless killing of pets in their London flat.

Eventually, the people in Emil’s life arrive at his apartment, knowing that he has just returned from London. Havard has no ready explanation for Emil’s absence. He simply tells them that he, too, came to visit, but Emil himself was gone—perhaps just stepping out for a moment to pick up some item. They accept Havard’s explanation, and as the guests become drunk, Emil’s absence is hardly noticed. As Emil watches from his hideout, he feels as if “I don’t really belong here, that this isn’t really my home.”

In part three of the novel, the attractive Greta arrives, and her strong, sensual presence changes the dynamic of the crowd in Emil’s apartment. On her arrival Emil falls further down the chain of existence, saying:

I get the feeling that they . . . are the ones who live here and that I am at most some sort of insect, some dust mite that has fallen onto the floor from the sheet to be sucked up in a few days when Greta orders Havard to get out the hoover.

Emil is drifting further from the human world. He muses that people have basic needs that he can no longer fulfill from beneath his bed: “alcohol, duvets, embraces, to enter one another.” Emil, beneath his bed, is little more than a bug.

In the end the trickster god of The Pets reigns supreme. There is no sense that this peculiar situation will end immediately, either for good or ill. The Pets is a novel that highlights the strange, twilight life of Icelanders. Behind the random meetings and happenstances in the novel, the author provides a stinging critique of his culture. In The Pets, consumption does not lead to either happiness or emptiness. In the same way, both extreme joy and terrible sadness are restrained. Author Bragi Ólafsson masterfully paints a picture of a colorless Iceland populated by people who have been rendered dull by a vapid culture, a stalled economy, and an adolescent need for immediate gratification. He does this with humor, restraint, and a sharp sense of the surreal potential of human reality.

But Ólafsson’s accomplishment in The Pets reaches beyond Iceland. This dark, turbulent, funny story is taking an ontological stand: Life is both boring and chaotic at the same time, oddly static yet constantly changing. The Pets cleverly, cuttingly, suggests that life is an arena where things can be both dangerous and impotent at the very same moment, and that we are helpless in the face of these ironies.

About the Reviewer

Eric Maroney has published two books of nonfiction and numerous short stories. He has an MA in philosophy from Boston University. He lives in Ithaca, New York, with his wife and two children and is currently at work on a book on Jewish religious recluses, a novel, and short stories.