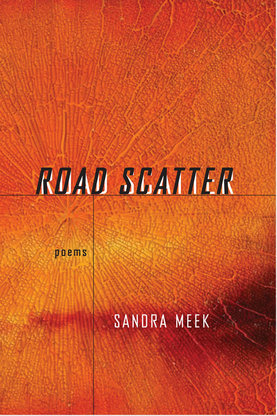

Book Review

Road Scatter, Sandra Meek’s devastating new book of poetry, aches with a sense of loss that is not only personal (the collection is dedicated to her mother), but historical and global. This collection illuminates the fragility of our constructions—lives, buildings, societies—and their vulnerability to illness, folly, and the ravages of the natural world. Loss is portrayed as the common denominator among bodies, languages, and worlds, and the breakage of one overlaps with the breakage of another. The poems in Road Scatter expose this comingling as a way of finding presence even in the most painful absence.

Road Scatter, Sandra Meek’s devastating new book of poetry, aches with a sense of loss that is not only personal (the collection is dedicated to her mother), but historical and global. This collection illuminates the fragility of our constructions—lives, buildings, societies—and their vulnerability to illness, folly, and the ravages of the natural world. Loss is portrayed as the common denominator among bodies, languages, and worlds, and the breakage of one overlaps with the breakage of another. The poems in Road Scatter expose this comingling as a way of finding presence even in the most painful absence.

“Shadow Portrait” begins the collection in darkness, scans the landscape’s liminal space to find “the last commas of her hair,” her mother’s hair scattered in language. She finds, “cursive stringing / letter to letter in quartertone slide.” In an allusion to the elegiac tradition, these images initiate the poet’s work not as a refashioning of the lost body of the beloved into, say, a wreath or flute, but as the work of locating the body as language already embedded in the world. The commas, letters, and cursive stringing are pieces of the language shared by the human and nonhuman realms that are discovered with eyes peering through the lens of grief. And while these fragments of language do not provide meaning, they indicate a path toward acceptance of what is, a path that begins and ends in poetry. The final couplet of “Shadow Portrait,” “I trace her to— / there, where the light ends,” locates the border between light and dark, grief and acceptance. It is where two worlds meet—daughter and mother, personal and universal, local and global—and fuse into one.

From this place of meeting, Meek’s poems zoom out toward origin, where the particular can be traced back to the historical, the collective. In “Columba Livia,” Meek writes:

Then

the farms moved inland until the frontier was desert

skewered with outsized windmills, spinning tridents

scissoring errant wings. Back home, what might be called country,

we call them doves: rock

to distinguish from mourning.

The mind reels back to consider how “country” derives from frontier, how knowledge of fauna defines a childhood. The “I” of the poem is swept back in time to “we.” Even the title wrings an intimate memory from Latin classification, from an inherent order.

In “The History of Air, Part I,” Meek again casts her gaze backward:

Once there was a once, a story

she added each night to

until the calendar slipped

from the wall, her blood running

away from my hand’s small pressure

Similar to the Latin classification of the previous poem’s title, “once,” is a gesture toward the shared—something of a historical commonality—out of which stems her particular grief. Indeed, once there was innocence, but the once-ness of life is over; what remains is the body breaking down, the brittleness of all bodies and of language. Two stanzas later, when this word reappears, it signals not innocence, but a present absence:

the doorknob she could turn,

once, when constellations glittered

until she clicked them

off behind blinds underscoring

the night she no longer

Here, “once” is loosed from its prior connotations by grief, freed from its storytelling context. And yet, it harkens back to the first stanza, indicating a breakage of language as the poem progresses. It is a powerful moment that reveals breakage as a transformation not only of the body, but also of language. Indeed, what is wrested from grief—the poem—is vulnerable to the same transformation as grief itself.

Additionally, as structures crumble and humanity declines in poems like “New Construction” and “Urban Warfare as Design,” we see the various manifestations of illness. We see how “the scaffold of bone / breaks down, as a toothpick-thin ship threads // away from its bottle’s blown glass.” In the eyes of grief, the human body’s breakage is everywhere. We read through Meek’s eyes the fragility of the things we make. In this case, it is a tangible thing, a building, but in “The History of Air, Part I” and almost everywhere in Road Scatter, it is the life we make that is fragile.

Similarly, in “Urban Warfare as Design,” a heart and a gun are elided through the image of their chambers, both indicating weakness:

Even cornered, the torn body zeroes on healing

its own jagged edges, even as the body tumbles

from chamber to barrel, repeating the pattern again,

again.

In this poem, the body that breaks isn’t just the victim, but the body politic, how we treat one another across societies. This, too, is ill, and the way in which Meek portrays violence here and in the poem “Marble Figure, Descending Panorama,” indicates a grief that spreads from personal to global loss. In the gripping “In Case, Since You Left, You’ve Been Wondering,” Meek writes, “the body is a slackening slab of terror // and loneliness, and why.” And while the “why” continues with “isn’t there a mother machine to never run out,” its line break indicates a disquiet, a generalized frustration spurred by the violence of people that crops up intermittently throughout the collection.

All of these explorations of breakage in Road Scatter—be it structural, natural, or of the body politic—render the moments interior to the book’s primary sense of loss all the more devastating. “Air Hunger” begins:

What you hear, barely, the body’s

last music: sword

of snow melt, stalactites’

mineral drip. Struggle is what no longer

translates: her sleeping

mouth open, the way a snake

unhinges—

Devastation comes from how closely Meek allows her poems and her readers to get to “the body’s / last music.” The s sounds in this passage stand in for her mother’s lack of speech; they coil around the poem and do not relent, for relenting the music of the poem, the music of the body, would mean the loss of what sustains it: language. Indeed, these s sounds wrest a moment of poetic intimacy out of a moment of experiential intimacy. They represent how the poetic can be wrested from the experiential, bearing the mark of their wresting in their very fabric.

Similarly to this use of alliteration, the persistent image of light functions as a remnant of the act of wresting the poetic out of the experiential. The repetition, the constant glancing up toward light in its various incarnations evokes the desire for acceptance and grace. The poems “Marble Figure, Descending Panorama,” “On Vengeance,” “Moth Season,” “Live Performance,” “Fifteen to Twenty,” and “Last Rites” perform this upward glancing throughout the collection. And although the “petrified light” of “On Vengeance” may seem like a different light than the “one bare lit bulb” of “Moth Season,” in the world of Road Scatter, which is our world, these lights are one and the same. Indeed, our moon is the same moon from wherever it is viewed.

The image of light unites this collection just as loss unites the realms of body, language, and world. Road Scatter crosses these realms with agility and insight, ending with “the water rising / darkest where the light begins.” This image mirrors the shadow in “Shadow Portrait” where the collection begins, an image that portrays breakage not as irrevocable loss, but as transformation. Perhaps this revision of breakage is Road Scatter’s greatest accomplishment. Grief may make us see transformation as breakage, but it is the work of the poem, the work of this startling collection, that allows us to see breakage as the transformation it truly is.

About the Reviewer

Christopher Kondrich is the author of Contrapuntal (Parlor Press, 2013). New poems also appear or are forthcoming in American Letters & Commentary, Boston Review, Guernica, Jerry, The Paris-American and Washington Square. A recent winner of The Paris-American Reading Series Contest, he is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Denver and an editor for Denver Quarterly.