Book Review

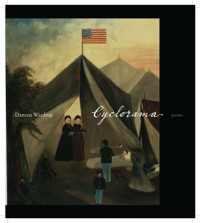

In her stunning new collection Cyclorama, Daneen Wardrop applies the unique artistic resources of poetry to the task of social history. Structured as an extended sequence of linked persona pieces, the work in this finely crafted volume eschews the great figures of the American Civil War to give voice to individuals who may otherwise have remained voiceless: wives, children, and the invisible labor that sustained an entire nation. As polyphonic as it is seamless in its construction, Cyclorama prompts us to consider history as collective mythmaking, calling our attention to the narrative impulse within each of us that makes meaning possible, even in the wake of violence, trauma, and social upheaval. As Wardrop engages these ambitious questions about history and the cultural imagination, her technical virtuosity adds myriad possibilities to an already rich and accomplished volume.

In her stunning new collection Cyclorama, Daneen Wardrop applies the unique artistic resources of poetry to the task of social history. Structured as an extended sequence of linked persona pieces, the work in this finely crafted volume eschews the great figures of the American Civil War to give voice to individuals who may otherwise have remained voiceless: wives, children, and the invisible labor that sustained an entire nation. As polyphonic as it is seamless in its construction, Cyclorama prompts us to consider history as collective mythmaking, calling our attention to the narrative impulse within each of us that makes meaning possible, even in the wake of violence, trauma, and social upheaval. As Wardrop engages these ambitious questions about history and the cultural imagination, her technical virtuosity adds myriad possibilities to an already rich and accomplished volume.

In a literary landscape filled with autobiographical writing, it is truly refreshing to see poems arising from an archival practice. Based on both paintings and written texts, Cyclorama exhumes voices from the past that risk erasure, presenting us with an American history that is narrated by many, rather than the few. Each persona poem offers us a fragmentary narrative grounded in deeply personal risks, losses, and anxieties. And so form becomes an extension of content, suggesting that the creation of meaning is a collective endeavor, as we all contribute to a shared cultural imagination. Wardrop reminds us of both our privilege and our responsibility, as history is a ongoing task, rather than a given. As a result, the narratives that circulate within society are subject to constant revision, opening up possibilities for introspection, and, in many cases, intervention. Consider this passage:

. . . we want to walk this minute into that sky room

and read the myriad names of soldiers who scratched signatures in every

direction,

shingled the place to the inch with angled hands.

want to finger the marks,

add ours to the cross-cross,

Jimmy lying down, digging his in a space just above the floor

and I etching mine with the “i” dotted by a script already there . . .

History becomes a palimpsest, one that is written, erased, and written over again. As the collection moves seamlessly from one voice to another, we are constantly reminded of the inherent instability of narrative. Each point of view, each subjectivity, offers a fundamentally different assessment of what is at stake, and even more provocatively, the place of the individual in relation to the collective. History is revealed not as a single authoritative entity, but rather a luminous and complex web of narratives that overlap and intersect.

With that in mind, Wardrop’s treatment of time in the collection proves especially noteworthy as the book unfolds. By eschewing more traditional approaches to writing history, and embracing fragmentation, Wardrop allows time to become recursive and elliptical, doubling back on itself. In other words, time is no longer linear, serving as a foundation for master narratives and the destructive war culture such narratives often work to justify. Rather, time’s nonlinear structure reveals the motifs, symbols, and shared beliefs that appear and reappear across multiple temporal moments. Wardrop’s innovative treatment of time, then, enables us to treat history as a text, inviting a greater degree of introspection and self-awareness. Wardrop writes, for instance, in “Process of Drafting in New York”:

A hand dips in a wheel.

Three o’clock in the afternoon.

Smoke may tear at faces.

I hate three o’clock in the afternoon.

After the slow, slow reel,

a hand steeping in a wheel.

Here a single temporal moment is revealed as a multiplicity, folding in on itself again and again. Indeed, each moment contains past, present, and future through Wardrop’s subtle, yet powerful, use of repetition. It is “three o’clock in the afternoon” over and over again, evoking this short duration as a labyrinth, a darkened room in which the speaker’s psyche is made to wander indefinitely. While reminiscent of H.D.’s recursive model of time in Helen in Egypt, as well as more contemporary and equally subversive discussions of temporality in the work of Joanna Ruocco and Kerri Webster, Wardrop’s work remains singular in that she demonstrates how our understanding of time arises from voice, narrative, and the cultural milieu surrounding them. In short, Cyclorama is a beautifully rendered book, as rich in its philosophical underpinnings as it is finely crafted. Wardrop is certainly a poet to watch.

About the Reviewer

Kristina Marie Darling is the author of over twenty books of poetry. Her awards include two Yaddo residencies, a Hawthornden Castle Fellowship, and a Visiting Artist Fellowship from the American Academy in Rome, as well as grants from the Whiting Foundation and Harvard University’s Kittredge Fund. She is a graduate of both the PhD program in literature at SUNY-Buffalo and the MFA poetry program at New York University.