Book Review

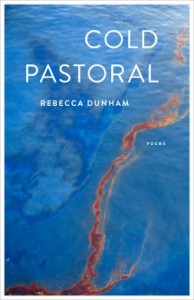

Pastoral poems traditionally idealize the rural countryside. They praise unfettered simplicity and examine spaces where it is difficult to comprehend urban decay. Yet, in Rebecca Dunham’s most recent collection, Cold Pastoral, there is mostly disaster. The unyielding truculence of land and sea are brought to life. Like John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” from which the collection takes its title, Dunham is interested in the coalescence among artistic purpose, beauty on earth, and the realization of one’s own mortality. Using a hybrid of ecopoetry, found documents, meta-criticism, and journalistic interviews, the collection centers around eleven bodies lost forever in the Atlantic Ocean. These are the bodies of the eleven workers who were never found after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill which, though not the sole focus of Dunham’s collection, is most certainly its ground zero.

The ethical implications of poetry itself become equally as important to Dunham’s work. In “A Hive of Boxes,” a lengthy prose poem which examines the poet’s research process and fascination with the fallout from Deepwater Horizon, Dunham writes:

In other words: The poet grieves not only a particular death, a

particular extinction. She mourns the death of nature itself, as

if it has already come to pass.

There is a distinct duality in Dunham’s understanding of “the death of nature itself.” Cold Pastoral not only elegizes those who lost their lives at the irascible patterns of their environments, but also seems aware that the extinction of the natural world is an Anthropocene inevitability. These poems take careful note of the methods by which humans are destroying the Earth, as well as the ways in which the planet is fighting back. They suggest ultimate annihilation is not a cataclysmic event, but a slow-going process on scales ranging from personal to global levels. For example, “Elegy for the Eleven,” a five-part poem mourning the men lost after the Deepwater Horizon explosion, considers the Earth’s reaction to being penetrated:

If earth is a blue balloon, is kelp

bladder, then the drill’s bit is a pin pushed

as far as it can go, until—everything

that could go wrong was going

wrong. He’d call before and after

every shift. I think the earth is

telling us she just doesn’t want

to be drilled here, he said.

Dunham’s poems are piercingly aware of this fragile interconnectedness, and additionally debate art’s empathic intentions. In a later section of “Elegy for the Eleven,” Dunham writes, “No, the other writer says, / it is the job of poetry to feed / empathy, and the end justifies any means.”

Cold Pastoral also delves into a wide range of other environmental catastrophes: the Flint water crisis, homes destroyed by tornadoes, the rampant health complications resulting from toxic insecticides, and the vastly unequal distribution of food. “Suburban Elegy,” for example, begins with a stark government statistic:

In 2010, the prevalence of household food

insecurity in suburban areas was

12.6 percent (6.2 million households)

US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

The paved street on which they live

has sent out roots,

tarred black, to split

cul de sac and yard.

While the poem focuses on the domestic food crisis, the opening lines reveal the connected ecosystem in which these disasters take place. The harsh division between grass and asphalt highlights the average American’s unshakeable dependence on oil. Asphalt itself is a semisolid petroleum product and the suburban spaces created by its sprawling tendrils require transportation in the form of gas-reliant automobiles. It’s easy to imagine two cars with poor fuel economy in every driveway, designed to shepherd children to sporting events or to stow bulk groceries. The verdant front lawn becomes a mere façade, a false oasis symbolizing middle class status smack-dab in an area where food is either unavailable or unaffordable; indeed, an area that has been plotted off by paving over the natural landscape. It’s not only the cost of food, but also the cost of getting to the source of food which create financial and environmental burdens.

“Elegy, Wind-Whipped” likewise distances itself from the catastrophe off the Gulf Coast, instead placing readers in the aftermath of a tornado. “You do not like / to say it, but you need / the dogs. No tools you possess / can help you find silence.” Human effort to locate injured survivors is reliant on the stronger senses of other animals. Manmade innovations aren’t an effective means of salvation in a time of true need. More broadly, humans must rely on other species to fill their natural weaknesses. Humanity is not independent of the ecosystem.

Throughout these seemingly unaffiliated disasters, the Deepwater Horizon oil spill becomes thematically omnipresent through the looming presence of corporate greed. Dunham, on the lyrical and journalistic level, deftly casts blame on BP, and thereby transitively on other massive, faceless corporations. Within poems dedicated to each of the eleven workers who died in the rig’s explosions lies the clear suggestion that wealthy oil executives valued cutting costs over the safety of their workers. Perhaps there is an even more tragic underlying message—the public will quickly forgive and forget such incidents so long as they don’t affect the status quo.

While, indeed, much of Dunham’s subject matter is bleak, many of the poems maintain an idyllic tone in the midst of capturing destruction. As a whole, Cold Pastoral presents a sense of serenity in the wake of humanity’s tumultuous relationship with the natural world. Hence the pastoral aesthetic is maintained, even though the subject matter is at times iconoclastic. The opening stanzas of “Backyard Pastoral” develop this sense of calm adeptly:

In her backyard, weeds proliferate,

bald dandelions, flocks

of garlic mustard, thistle. She straps

her son into his infant carrier,

face to her chest, and drapes

a thin blanket over his head.

To protect him from the sun.

In the tradition of pastorals, Dunham’s collection asks timely questions about the role of art in dire situations that demand action. How does the poet contribute to collective memory? Does mourning major crimes against Earth and its inhabitants discourage future environmental atrocities? Art, Dunham suggests, at the very least continues the conversation. In this way, Cold Pastoral bears witness and considers the value of testimony; these poems document both moments of self-inflicted carnage and the scars that remain long afterward. This reporting is done with an irenic sense of duty, the artist’s commitment to honor natural beauty in the face of death, and the somber realization that in all likelihood it’s already too late to stop the inevitable. Dunham’s elegies are therefore neither strictly for the planet nor its human occupants, but instead see their deaths as one ongoing, interlinked conundrum. They will thrive or perish together.

About the Reviewer

Aram Mrjoian is a contributor at Book Riot and the Chicago Review of Books. His reviews, interviews, and essays have appeared in many other publications, including TriQuarterly, Necessary Fiction, the Adroit Journal blog, and the Masters Review. His stories are published or forthcoming in Tahoma Literary Review, Gigantic Sequins, Limestone, the Great Lakes Book Project, and others. He is currently working toward his MFA in creative writing at Northwestern University, where he is a fiction editor at TriQuarterly.