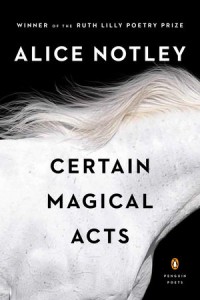

Book Review

If there is one great theme that runs through the course of Alice Notley’s work, it is that of power, and Notley’s latest collection continues that theme, making substantial claims for the power of poetry and imagination as a means of survival and redemption. Certain Magical Acts invites the reader to “wander . . . among migrating useless ideas,” while working to “disattach ourselves from those binding us to their use.” The book in many ways distills Notley’s prior collections into something more compactly epic and defiantly lyrical, even rhetorical at times.

If there is one great theme that runs through the course of Alice Notley’s work, it is that of power, and Notley’s latest collection continues that theme, making substantial claims for the power of poetry and imagination as a means of survival and redemption. Certain Magical Acts invites the reader to “wander . . . among migrating useless ideas,” while working to “disattach ourselves from those binding us to their use.” The book in many ways distills Notley’s prior collections into something more compactly epic and defiantly lyrical, even rhetorical at times.

Despite this continuity in theme, the poems feel new, surprising, and refreshing. Enchanted and incantatory, the poems of Certain Magical Acts resist convention and protocol, as Notley’s poems are wont to do, and they allow both poet and reader to not only create a new world but to occupy it together; not to use the poem, but to inhabit it: “We’ve come here to be mixed into one sound, / the dream, or is it voice, of us.”

This mixing is largely present in the formal decisions of the poems. Notley once referred to Frank O’Hara as the “better athlete” in regards to the structure and movement of his poems. Certain Magical Acts shows Notley at the peak of her own athleticism, shifting registers and formal constructions with apparent ease. This collection is quick to remind the reader that even when she claims she is inventing a new language, Notley works with and within poetic tradition—and part of that tradition is her earlier poetry. Over the course of Certain Magical Acts, the reader finds “expansive lines, . . . meters reminiscent of ancient Latin, . . . a postmodern broken surface, and the occasional sonnet.” This is a bit incomplete; the reader also finds prose poems as well as a more traditional lyric form, several Williams-like triadic stanzas. Frequently, these various forms bleed into one another, generating a productive interference: discrete, yet overlapping, measurements of events and time.

Oh There are several kinds

of time going on at the same time. That of the line, that of the

dead, and that of the leap.

The push and pull between expansive lines and spare moments of lyricism root the reader in the universe of the poems’ making. These formal movements make for “readable,” but still rather difficult poetry, demanding close attention as it negotiates time, juggles a number of voices, and insists upon internal contradiction. Instead of disorienting the reader, as can some of Notley’s more untamed (or untamed-seeming) work, Certain Magical Acts develops a sense of clarity of vision and purpose. The poems invest in a self-sustaining gift economy, a universe both created and contained by mind and poem: “We invented money when we could have invented the gift.” That the gifts in and of these poems are given by us, both poet and reader, as we experience them in kind, is Blakean in its impulse and still quite radical.

We are gravely and lightfully blessed,

but we bless ourselves. We are our way, but we fight

within and about it. We step on the fragile thread of our way,

going about with no other explanation but givenness: this

is our gift, but who or what can have given it to us except for us?

In a dying world, why do we need art? It is because in a gift economy, we are given the ability to re-world through the power of imagination and expression. Still, these poems are not blind to the ever-present suspicion of art’s power to affect change, going so far as to acknowledge that irreversible damage is indeed done to the earth.

And if roses imbued with carbon are what we love,

you say, and if frogs and tigers are dead, and honeybees,

small blue California butterflies, and any number of beautiful

creations, what good is this imagination?

What good; what use? Certain Magical Acts argues that we survive through that imaginative work, beyond “human breath as / register of process, profundity, and the real.” Working as much to survive the destruction of the old world as to create a new one from an original chaos, this collection insists the reader play an active role in the process of entering into “the real reality.” The poet, here, closely guides the reader:

We’re creating ourselves through thought and speech I am leading you

To porousness I am destroying politics I remember walk-

Ing on my street thinking I have achieved freedom who else has

It’s a state of nonpossession for the universe

As these poems know, with the power of creation comes the power of destruction, or at least of revision, and as the book draws the reader into self-creation, the poems ask the question, “When I leave to live in printed words, who am I?” This question is not one of identity, but rather of ontology. “I have no interest in being myself,” writes Notley, “I just am.” Poetry, in the universe of Notley’s writing, is magic, and these “certain magical acts” have the power to “combine my flesh / with yours, and you with mine,” affecting significant change. Maybe it’s wishful thinking, but maybe we’re in a time when wishful thinking—imaginative thinking—is most necessary.

With Certain Magical Acts, Notley, ever-willing to “disavow any reason but ink on / paper to be viewed in the future / by no one” remains one of our most necessary and relevant poets.

About the Reviewer

Meagan Wilson’s poetry and reviews have appeared in a number of publications. She holds an MFA from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and recently graduated from Colorado State University’s literature program. She will enter SUNY Buffalo’s Poetics program this fall.