Book Review

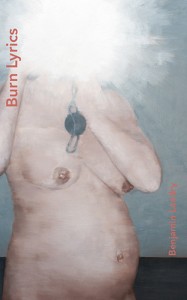

While as readers we’ve all been admonished to not judge a book by its cover, covers—and their copy—remain hard to ignore. The back cover of Benjamin Landry’s latest work, Burn Lyrics, is all the more intriguing for the bold claim Laura Kasischke makes: “Burn Lyrics is an entirely original accomplishment.” These words again insist upon the reader immediately upon opening the front cover. Kasischke is speaking to Landry’s endeavor, in writing Burn Lyrics, to complete—or perhaps more accurately, fill in? write around?—Sappho’s fragments, and while “entirely” might be a challenging expectation to deliver, the poet’s voice in these poems is certainly deserving of our attention.

As coincidence would have it, I’d just revisited Anne Carson’s translation of Sappho, If Not, Winter, this summer, retreating from the completion of an MFA program and the busyness of my own writing into her strange and ancient echo-lands. On the one hand, I was struck by the praise we give Sappho based on how little we truly have of hers—the line breaks are not her own, and undoubtedly the original verse was necessarily more verbose given how incomplete the fragments that survive, and yet, incredibly, what does survive is beautiful. Indeed, my first inclination going forward is to cut my own lines down to such capacious essentials. How curious, then, to arrive at Landry’s book, wholly opposite in its impulse—to fill in what is missing. An erasure in reverse.

My first reaction was that Landry’s experiment is sacrilege—how could one presume to speak over such devastating poems, and a male poet no less? And yet, as I settled into Landry’s collection, all the same old ghosts came to listen, “on the bank / like the dead who do not know they’re dead.” In these poems, Landry reaches back to find language capable of uncertainty—not to conquer that past, but to humble our own presumptive present with all we still do not, and cannot know. “Are we worth our salt? The newest / among us says, ‘I want to hold // said violet,’ and the rest of us suspect it won’t / work out but don’t want to interrupt.” These are poems, much like Sappho’s fragments, that are at once of a moment, like the early Rufous hummingbird, a “dynamo that barely touched down.” Similar, too, to the work of Jean Valentine, they contain narrative comfortable enough in its poem-skin to need not insist upon any kind of definitive authority. After all, “we’re born // not knowing where we belong.” Through these poems, Landry suggests a way to bridge time through language, so that the “cattle chute” in which “your wits are restive” place our present in a continuum of experience stretching back eons, and even if such vastness, like the violet, cannot be held, there is comfort in the attempt.

Returning to Kasischke’s initial claim, however, is the collection something entirely original? Perhaps it might be more accurate to call the work an original articulation of a common impulse. In a workshop I attended with poet Sherwin Bitsui, poets at varying stages in their education and careers were given words pulled at random from several poetry collections, which also had been selected at random. The poets were then tasked to incorporate these words into poems written on the spot. Though not of our choosing, these words called to mind images and words that at once held more personal resonance, yet nevertheless still echoed those initial borrowed words. So, too, certain erasures maintain some lingering association with their source, surely (Ronald Johnson’s Radi os, for example), and yet the erasures become poems in their own right, with gifts even for the reader unfamiliar with the source.

Landry has approached the art of erasure in reverse, so that something of the timeless, meditative tone of Sappho remains, no doubt amplified by one’s foreknowledge going into the work, and yet they become poems wholly separate. They are poems that remind us what it is to dwell in language, not at the exclusion of the real and living world around us with all of its pressing demands and concerns, but in respite, in retreat so as to look out at the world from the inside out, and so to approach living in such a world afresh.

Other poems in Burn Lyrics are rooted more firmly in the present: “I would not think to park on the near / side of the street; my signal through / the open window would indicate ‘It is I.’” Yet even these modern images summon some stillness out of time; in this particular poem, “Wild Grape,” this stillness is summoned through the evolving anaphoric use of Sappho’s fragment 52: “I would not think to touch the sky with my two arms.” Such poems also utilize line breaks to mimic the slowly unfolding understanding that happens when we read Sappho’s fragments as whole poems in spite of themselves:

after the dinner

crowd and toward

midnight

the one who waits

to the dark

glass

says this may be the last time

And still other poems take more liberty with their source. In the poem “Surveilled,” for example, one’s attempts to locate Fragment 147 in Landry’s verse becomes akin to a game of word search.

Indeed, Landry’s choice of fragments in which to write, as well as his order and approach to renovation, do not in themselves suggest a deliberate pattern or approach to his source. But then, nor can Sappho’s own relationship to and among her poems be known. Torn between past and present, stillness and our own hurried modern lives, where is the common ground on which the Rufous hummingbird from the early poem “You Keep” may alight? What vision out of Sappho’s fractured echoes does Landry present for our consideration? Perhaps the answer lies in a poem:

“Emotion’s a strange thing to have

conquered, as though to understand

fear is to master it—a mean

dog—and with delicate words.

…

held up to the sun. There’s so much

ground to be covered, and the present

taxonomy fails to convince. In short,

it’s a scorcher of an afternoon,

and yet her face sleets up well.”

Perhaps in these lines lie the secret to the closing poem of Burn Lyrics, “Objet Un.” Tonally, stylistically, and formally different than the poems that precede it, and following after Landry’s Fragment Sources Note, it is unclear the relationship this long poem bears to the larger project’s practice of writing with Sappho. No source fragment is listed. Perhaps then this is the sleet upon her face, “each version of this moment / further multiplied… fades from this / vantage strengthens from another / further down the chain of waters.” The waters of Burn Lyrics are indeed waters I intend to swim again.

About the Reviewer

Abigail Chabitnoy earned her MFA in poetry at Colorado State University and was a 2016 Peripheral Poets fellow. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Hayden’s Ferry Review, Pleiades, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Nat Brut, and Red Ink, and she has written reviews for the Volta blog and The Courier, a publication of the Wolverine Farm Press and Bookstore based in Fort Collins, CO, where she currently resides.