Book Review

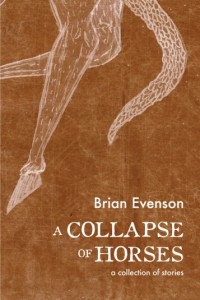

For a while people have been telling me Brian Evenson is funny. I admire Brian Evenson’s work, but funny? Odd, maybe. Surprising. Creepy. Fierce. But funny isn’t the word I would use to describe his stories of asphyxia and sinister doubles. Nor would I use the word to describe his stoic presence as he reads aloud from those stories. So I was surprised to find that some of the stories in his most recent collection, A Collapse of Horses, really are quite funny, and funny in an unusual way.

The finest stories in the collection, with one exception, are also the funniest. There’s “Past Reno,” which begins, “Bernt began to suspect the trip would turn strange when, on the outskirts of Reno, he entered a convenience store that had one of its six aisles completely dedicated to jerky.” It’s the first of many references to jerky, a pattern of conspicuous cured meat images that culminates in a traumatic memory:

He hesitated a moment, wondering what exactly his father had meant for him to see—whether it was the strips of meat or perhaps something else, something behind the racks, even deeper in.

The “something else” is never named; we only get the jerky!

Then there’s “Seaside Town,” whose premise is almost screwball comedy: a middle-aged homebody is convinced by his new girlfriend to pay for a European vacation so she can meet an old lover on the sly. But Evenson’s execution of that premise involves patterns of mysterious, ambiguous imagery that achieve his usual disquieting effect, in this case destabilizing the humorous setup—which isn’t to say the humor falls away. At one point the stodgy protagonist, abandoned by his girlfriend, gathers the courage to venture out of their room only to discover himself on a nude beach, where he’s humiliated by a hairy-chested sunbather. Humor veers quickly into discomfort, one of many such moments in the collection.

The exception—the story that’s too intense to be funny at all—is “The Dust.” The novella-length story first appeared in McSweeney’s and stands among Evenson’s finest. In it, a group of miners struggle at the Sisyphean task of keeping dust out of the breathing machine in their futuristic mining compound. The oxygen may or may not be running out. When they start getting killed, the protagonist, Orvar, wonders who among them is responsible. Nobody escapes Orvar’s suspicion, not even himself. Evenson plays a game with Orvar’s memory that those who have read Evenson’s novel Immobility will recognize. It’s one he plays to suspenseful effect.

Unlike “The Dust,” many of the most interesting stories in the collection are short and end abruptly, not unlike the stories in Windeye, Evenson’s previous collection. In “Cult,” a man feels inexplicably drawn to an ex-girlfriend who stabbed him. His friends try to keep him away from her, but when she calls him from a pay phone outside a cult that kicked her out, he can’t help but to go to her aid, only to take shelter (from her) in the very same cult. This is a peculiar story. Most of its energy comes from the mysterious ex-girlfriend, or the mystery of her hold on the protagonist, but Evenson doesn’t give us much. He leaves us with the pathetic ex-boyfriend at the cult. Critics of Evenson’s recent work might argue that stories like “Cult” aren’t full stories—that they’re stubs, or sketches. Most of these are Evenson’s wildest, bloodiest stories, which often end in what might be called cliff-hangers. We may wonder what grizzly fate awaits this or that character, but those fates are better left to our imaginations. In the case of “Cult,” however, I’m left wondering about the ex-girlfriend and her mysterious power. So while I appreciate the story, I do wish there were more of it. But better that feeling than its opposite. To use an example from a different medium: side two of Abbey Road is more interesting, if less catchy, than side one, but it wouldn’t have been nearly as interesting if the Beatles had forced themselves to expand “Polythene Pam,” for instance, into a full-fledged pop song. Many of the songs, like “Golden Slumbers,” might have been left off the album, which would have been a shame. And it would be a shame if A Collapse of Horses didn’t include “Cult” or “The Punish” or any of the others that make up for what they lack in endings with daring beginnings and middles.

I recommend A Collapse of Horses, stubs and all, to fans of Evenson’s work, fans of literary fiction, and fans of horror and fantastical fiction. While none of the stories in this collection reach the elegant heights of a few in Windeye (like “Windeye” and “The Second Boy”), the stories here are more consistently excellent, and more of a piece. There’s no “Bon Scott: The Choir Years” awkwardly sticking out. Let’s hope Evenson keeps writing collections like this, and Coffee House Press keeps publishing them, for years to come.

About the Reviewer

Bradley Bazzle's short stories appear in New England Review, New Ohio Review, Epoch, Web Conjunctions, and elsewhere, and have won awards from Third Coast and The Iowa Review. Some of them can be found at bradleybazzle.com. He lives in Athens, Georgia, with his wife and daughter.